CHAP. XX

Newse-River. Hillsborough. Stong Post. Haw

Fields. Singular Phenomena. Accounted for.

The last two considerable streams of water that I crossed on my way to this place, Fishing-creek and Tar-river, receiving several inferior creeks and branches in their course, form a tolerable large river, which passing by Tarburg, falls into the immense body of water, that is known by the appellation of Pamplico sound, at the Bath town, after a course of about an hundred and fifty miles, in a direct line, from the source.

It was in February when I left this place, and again proceeded on my journey.

At the end of two miles, I crossed Flat river, and in two miles farther, Little river; these, with another river (the Eno) within a couple of miles more, meet some small distance below, and form the river Newse.

Each of these small rivers, is larger than the Thames at Richmond, and the Newse is not much inferior to the Roanoak.

After a course of more than three hundred miles, it empties itself in Pamplico sound, about thirty miles below the town of Newbern, which is sometimes called and lately established as the capital of North-Carolina.

This town is situated in a very beautiful spot, on the banks of the Newse, at the confluence of a pretty stream, named Trent river.

After a ride of twenty-two miles, I arrived at Hillsborough, where I dined and passed the rest of the day.

This is the third appellation this town has already been honoured with since it was erected, being first named Corben town, next Childsburg, now Hillsborough; all in less than thirty years.

It is also the capital of a district, and the county-town of Orange.

Hillsborough is a healthy spot, enjoys a good share of commerce for an inland town, and is in a very promising state of improvement.

The land for some distance around Hillsborough, consists of a mixture of loam and strong red clay of so bright a colour that white horses and cattle, soon after they are brought there, become in appearance a fine scarlet. [I suppose this is true in a way, but really, scarlet?]

In the vicinity of Hillsborough, and to the westward of it, there are a great many very fine farms, and a number of excellent mills.

The inhabitants are chiefly natives of Ireland and Germany, but of the very lowest and most ignorant class, who export large quantities of exceeding good butter and flour, in wagons, to Halifax, Petersburg, &c. besides multitudes of fat cattle, beeves [beefs], and hogs.

There is a very steep and high hill, or small mountain, with two summits of an equal height, on the south-west of Hillsborough, which arises abruptly in the middle of an extensive plain, and commands the whole country for a great distance around.

This might easily be rendered a very strong post, by works thrown up on the summits, which are near enough to cover and support each other, and so situated, as the communication between them could not be interrupted. The flanks and rear likewise would be strengthened by the river Eno, which runs at the base of this mountain, and two sides of it. [Such an unusual perspective on Occaneechee Mountain. Says a lot about the author and his times.]

The staple produce of all this country being provisions of every kind, a fortified post in this place would thereby be enabled to subsist and maintain itself in every necessary supply, excepting arms and ammunition, and might be defended, by a small force, against a very considerable and superior army.

Almost every man in this country has been the fabricator of his own fortune, and many of them are very opulent.

Some have obtained their riches by commerce, others by the practice of law, which in this province is peculiarly lucrative and extremely oppressive; but most of them have acquired their possessions by cropping, farming, and industry. [Pretty much what the War of the Regulation was all about.]

I dined next day, by invitation, at the house of Mr. Frank Nash.

{Since then it has happened, in the vicissitudes of fortune, that Mr. Nash and the author were engaged in battle on different sides; Mr. Nash as a General in the American army, and the author a Captain in the British, at the action of German-Town, near Philadelphia, where Mr. Nash received his mortal wound.}

Here, at Mr. Nash’s, I happened to meet a Mr. Mabin [Alexander Mebane presumably] (a native of Ireland) who very kindly insisted on my accompanying him to his seat on Haw river, adjoining the Haw fields, to spend some weeks there.

Having a great desire to view the Haw fields, a place I had heard much about, I went along with him to his plantation, which is about an easy day’s ride, west of Hillsborough.

Mr. Mabin’s farm is very valuable and extensive, but not particularly remarkable. [Mr. Smyth Stuart is not a terribly gracious guest.]

I rode several times over the Haw fields, but could not perceive any thing in them extraordinary. [You know, John Lawson said of this area: "the Land is extraordinary Rich, no Man that will be content within the Bounds of Reason, can have any grounds to dislike it. And they that are otherwise, are the best Neighbours, when farthest of[f]." So I guess we know who Lawson was talking about.]

They consist partly of wide savannahs, or glades, and partly of large fields overgrown with shrubs, brush, and low under-wood, entirely destitute of heavy timber. But there appears many vestiges of trees, which in all probability have been blown down by a hurricane, and the young shoots afterwards choaked by the extreme thickness of the low bushes, and scrubby underwood. This I have also observed to be the case in many other places besides. [Sounds doubtful.]

From the effect of these most violent and tremendous hurricanes and tornadoes, which being sometimes partial, frequently move in strange and fantastic directions, and from the irresistible force of the wind, and the vast deluges and inundations of water that generally accompany them, all the appearances may be readily

[It seems as though the typographer omitted a portion of the text here. There is a page break before the next word and I think maybe an entire page was erroneously omitted.]

accounted for in a common natural way, which, however, have lately given scope to an ingenious, celebrated and elegant author’s (Dr. Dunbar) and others of less note (Mr. Carver,&c.) vague imaginations; hazarding their fanciful and wild conjectures of some of these being vestiges of military works erected many ages past by a people then conversant in the science, but whose descendants, by the mere dint of practice, (for war and hunting appear from the most early period of time to have been the sole study and occupation of their lives,) and by some other equally absurd and unaccountable transitions, have thereby forgotten, and, at this day, have lost every trace thereof.

Indeed it must be confessed, that the elephant’s bones, or those of some other unknown animal of vast magnitude, found on the banks of the river Ohio, the antique sculptures in the Delaware’s country, on the north-west side of that amazing river, the shells and marine substances in the Alegany mountains, together with many other strange appearances and singular phenomena, so frequently to be met with throughout this most extensive continent, display a fertile field for a creative, fanciful genius to explore, and may give rise to the most novl, elegant, and beautiful flights of imaginstion, and the brightest, most ingenious and splendid embellishments of fiction. [He sure has a way of wandering pretty far afield.]

However, I have reason to believe, that some of the Haw fields have been cleared of woods by the Indians, in ages past, who were undoubtedly settled here; many insignia, and vestiges of the remains of their towns, still remaning. [So generous. All authorities certainly agree the that Haw old fields are far older than the European settlers.]

Saturday, October 3, 2009

Chapter 21 of Smyth-Stuart's A Tour in the United States (1784)

CHAP. XXI.

Haw river. Deep river. Cape Fear river. Carroway mountains. Grand and elegant Perspective. Bad Accomodations. Unsuitable to an Epicure, or a Petit Maitre.

Having it in speculation to visit Henderson’s settlement on Kentucky, I mentioned my intention to Mr. Mabin [Mebane], who appeared very strenuous in dissuading me from undertaking such an enterprise at present, on account of the misunderstanding and disturbances now subsisting between the Indians and the Whites.

He informed me of a report, that even Henderson’s whole settlement was either exterminated, or in imminent danger of being so.

For this reason, I concluded to postpone this arduous undertaking, until such time as more certain and favourable intelligence of their situation in the settlement should arrive, and a better prospect of reaching it without molestation.

On the third evening after I came here, a gentleman, named Frohawk [Thomas Frohawk, the Clerk of Court in Salisbury?], called at Mr. Mabin’s, on his return to Salisbury, where he resided.

As he tarried all night, we had much conversation, and form his accounts of the Catawba Indians, my curiosity was strongly excited to visit their nations, which was only about an hundred miles beyond the town of Salisbury.

Accordingly, having expressed my desire and intention to Mr. Forhawk, he was so obliging as to propose to conduct and accompany me; an opportunity and eligible offer, which I with great satisfaction embraced, and set out along with him next morning.

The road we traveled in is named the Great Trading Path, and leads through Hillsborough, Salisbury, &c. to the Catawba towns, and from thence to the Cherokee nation of Indians, a considerable distance westward.

We forded the Haw river [Presumably at Swepsonville, NC], which is there about twice as broad as the Thames at Putney, and within a few miles farther, in the like manner, we crossed Reedy river [I think he must mean Alamance Creek or possibly Rock Creek], another branch of the same stream and as large.

We dined just by a Quaker’s meetinghouse (no modern Quaker Meeting House lies along this course, as far as I can tell; no idea what Meeting House it might have been), and in the afternoon crossed the Deep river, at a ford [probably at Randleman, NC]. This is also about twice as wide as the Thames at Putney, and joins the Haw river some distance below, after washing the base of the north-east side of a ridge or chain of high hills, named the Carroway mountains.

The Haw is then a large river, and runs through the settlement and town of Cross creek [Fayetteville, NC], which is chiefly inhabited by Scots emigrants from the western Highlands and the Hebrides; it then assumes a new appellation, being called the Northwest, or Cape Fear river, and passing by the town of Wilmington, which has been frequently considered as the metropolis of North-Carolina, on the north-east, and Brunswick, which is a little lower on the western bank of the river, it falls into the Atlantic ocean at Cape Fear, after a course of more than three hundred miles from the source.

We lodged that night at an inn or ordinary, as it is called here, at the foot of the Carroway mountains, which we had frequently had a glimpse of, during this day’s ride. [I wonder if this ordinary could be identified? None is shown on the Hughes Hist. Doc. Map of Randolph. Need to look at the G P Stout map.]

We pursued our journey early on the following morning, which was extremely pleasant and fine; and when we arrived at the summit of the mountain, the sun just began to verge above the horizon.

Here I alighted, and indulged myself in gazing with great delight on the wild and extensive prospect around me.

On the north-east I beheld the mountains at Hillsborough, distant above fifty miles; on the south-west, the mountains near Salisbury; and on the west, Tryon mountains; with the wide extended forest below, embrowned with thick woods, and intersected with dark, winding, narrow chasms, which marked out the course of the different mighty streams that meandered through this enormous vale; thinly interspersed on the banks of which, the farms and plantations appeared like as many insignificant spots, that, while they pointed out the industry, served also to expose the littleness of man. [Although I bet the view from here is still excellent, I doubt that it would any longer ‘expose the littleness of man.’]

On this spot I could with pleasure have passed the day, had not a craving, keen appetite reminded us, that there are more gratifications necessary for our support, than feasting our eyes; so we descended the mountain, and pursued our journey.

It was fortunate for me, that at this time, my constitution, health, and taste, enabled me to subsist on any kind of food, without repining, and with sufficient satisfaction, however coarse or unusual it might be. For this is not an enterprise for an epicure, or a petit maitre: the apprehension of perishing with hunger and want, would as effectually deter the one from such an undertaking, as the dread of absolutely expiring with fatigue with and hardships, would the other; the fare and accommodations a traveler meets with throughout this country, being very indifferent indeed, even at best, and generally miserable and wretched beyond description, excepting at ward or opulent planters houses, where there is always a profusion of every thing, but in the coarsest and plainest style. [I don’t really doubt him, but I have to say that he is such a whiner.]

The greater number of those who travel through this country, have acquaintances among the inhabitants, at whose houses they generally put up every night, and seldom call at ordinaries.

Those that drive and accompany waggons on a journey, sleep in the woods every night under a tree, upon dry leaves on the ground, with their feet towards a large fire, which they make by the road side, wherever night happens to overtake them, and are covered only with a blanket. Their horses are turned loose in the woods, only with leather spancills or fetters on two of their legs, and each with a bell fastened by a collar round his neck, by which they are readily found in the morning. Provisions and provender, both for men and horses, are carried along with them in the wagon, sufficient for the whole journey.

Even these advantages, trifling as they may appear, a traveler on horseback is destitute of, and is obliged to trust to Providence, and the country through which he passes, for accommodation and subsistence; both of which are not always to be me with and even when they are, are seldom as good, never better than the waggoners.

CHAP. XXII.

Yadkin River. Salisbury. Beautiful Perspective. Tryon Mountain. Brushy Mountains. The King Mountain distinguished for the unhappy Fate of the gallant Major Ferguson.

Late in the afternoon we crossed the river Yadkin, at a ford, six or seven miles beyond which is the town of Salisbury, where we arrived that evening, being about one hundred and twenty miles west-southwest- from Hillsborough.

[The author continues his narrative, describing King’s Mountain, Salisbury and the land beyond, but it moves outside the scope of this blog, so I will stop transcribing here.]

Haw river. Deep river. Cape Fear river. Carroway mountains. Grand and elegant Perspective. Bad Accomodations. Unsuitable to an Epicure, or a Petit Maitre.

Having it in speculation to visit Henderson’s settlement on Kentucky, I mentioned my intention to Mr. Mabin [Mebane], who appeared very strenuous in dissuading me from undertaking such an enterprise at present, on account of the misunderstanding and disturbances now subsisting between the Indians and the Whites.

He informed me of a report, that even Henderson’s whole settlement was either exterminated, or in imminent danger of being so.

For this reason, I concluded to postpone this arduous undertaking, until such time as more certain and favourable intelligence of their situation in the settlement should arrive, and a better prospect of reaching it without molestation.

On the third evening after I came here, a gentleman, named Frohawk [Thomas Frohawk, the Clerk of Court in Salisbury?], called at Mr. Mabin’s, on his return to Salisbury, where he resided.

As he tarried all night, we had much conversation, and form his accounts of the Catawba Indians, my curiosity was strongly excited to visit their nations, which was only about an hundred miles beyond the town of Salisbury.

Accordingly, having expressed my desire and intention to Mr. Forhawk, he was so obliging as to propose to conduct and accompany me; an opportunity and eligible offer, which I with great satisfaction embraced, and set out along with him next morning.

The road we traveled in is named the Great Trading Path, and leads through Hillsborough, Salisbury, &c. to the Catawba towns, and from thence to the Cherokee nation of Indians, a considerable distance westward.

We forded the Haw river [Presumably at Swepsonville, NC], which is there about twice as broad as the Thames at Putney, and within a few miles farther, in the like manner, we crossed Reedy river [I think he must mean Alamance Creek or possibly Rock Creek], another branch of the same stream and as large.

We dined just by a Quaker’s meetinghouse (no modern Quaker Meeting House lies along this course, as far as I can tell; no idea what Meeting House it might have been), and in the afternoon crossed the Deep river, at a ford [probably at Randleman, NC]. This is also about twice as wide as the Thames at Putney, and joins the Haw river some distance below, after washing the base of the north-east side of a ridge or chain of high hills, named the Carroway mountains.

The Haw is then a large river, and runs through the settlement and town of Cross creek [Fayetteville, NC], which is chiefly inhabited by Scots emigrants from the western Highlands and the Hebrides; it then assumes a new appellation, being called the Northwest, or Cape Fear river, and passing by the town of Wilmington, which has been frequently considered as the metropolis of North-Carolina, on the north-east, and Brunswick, which is a little lower on the western bank of the river, it falls into the Atlantic ocean at Cape Fear, after a course of more than three hundred miles from the source.

We lodged that night at an inn or ordinary, as it is called here, at the foot of the Carroway mountains, which we had frequently had a glimpse of, during this day’s ride. [I wonder if this ordinary could be identified? None is shown on the Hughes Hist. Doc. Map of Randolph. Need to look at the G P Stout map.]

We pursued our journey early on the following morning, which was extremely pleasant and fine; and when we arrived at the summit of the mountain, the sun just began to verge above the horizon.

Here I alighted, and indulged myself in gazing with great delight on the wild and extensive prospect around me.

On the north-east I beheld the mountains at Hillsborough, distant above fifty miles; on the south-west, the mountains near Salisbury; and on the west, Tryon mountains; with the wide extended forest below, embrowned with thick woods, and intersected with dark, winding, narrow chasms, which marked out the course of the different mighty streams that meandered through this enormous vale; thinly interspersed on the banks of which, the farms and plantations appeared like as many insignificant spots, that, while they pointed out the industry, served also to expose the littleness of man. [Although I bet the view from here is still excellent, I doubt that it would any longer ‘expose the littleness of man.’]

On this spot I could with pleasure have passed the day, had not a craving, keen appetite reminded us, that there are more gratifications necessary for our support, than feasting our eyes; so we descended the mountain, and pursued our journey.

It was fortunate for me, that at this time, my constitution, health, and taste, enabled me to subsist on any kind of food, without repining, and with sufficient satisfaction, however coarse or unusual it might be. For this is not an enterprise for an epicure, or a petit maitre: the apprehension of perishing with hunger and want, would as effectually deter the one from such an undertaking, as the dread of absolutely expiring with fatigue with and hardships, would the other; the fare and accommodations a traveler meets with throughout this country, being very indifferent indeed, even at best, and generally miserable and wretched beyond description, excepting at ward or opulent planters houses, where there is always a profusion of every thing, but in the coarsest and plainest style. [I don’t really doubt him, but I have to say that he is such a whiner.]

The greater number of those who travel through this country, have acquaintances among the inhabitants, at whose houses they generally put up every night, and seldom call at ordinaries.

Those that drive and accompany waggons on a journey, sleep in the woods every night under a tree, upon dry leaves on the ground, with their feet towards a large fire, which they make by the road side, wherever night happens to overtake them, and are covered only with a blanket. Their horses are turned loose in the woods, only with leather spancills or fetters on two of their legs, and each with a bell fastened by a collar round his neck, by which they are readily found in the morning. Provisions and provender, both for men and horses, are carried along with them in the wagon, sufficient for the whole journey.

Even these advantages, trifling as they may appear, a traveler on horseback is destitute of, and is obliged to trust to Providence, and the country through which he passes, for accommodation and subsistence; both of which are not always to be me with and even when they are, are seldom as good, never better than the waggoners.

CHAP. XXII.

Yadkin River. Salisbury. Beautiful Perspective. Tryon Mountain. Brushy Mountains. The King Mountain distinguished for the unhappy Fate of the gallant Major Ferguson.

Late in the afternoon we crossed the river Yadkin, at a ford, six or seven miles beyond which is the town of Salisbury, where we arrived that evening, being about one hundred and twenty miles west-southwest- from Hillsborough.

[The author continues his narrative, describing King’s Mountain, Salisbury and the land beyond, but it moves outside the scope of this blog, so I will stop transcribing here.]

Saturday, September 26, 2009

The Iron Mountain Spur

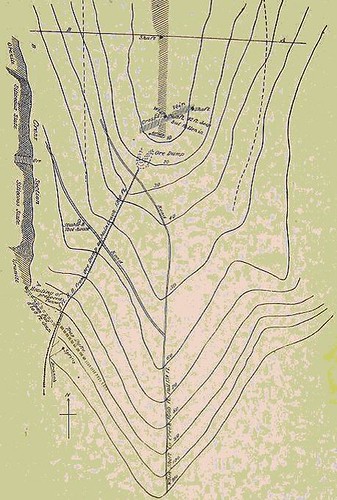

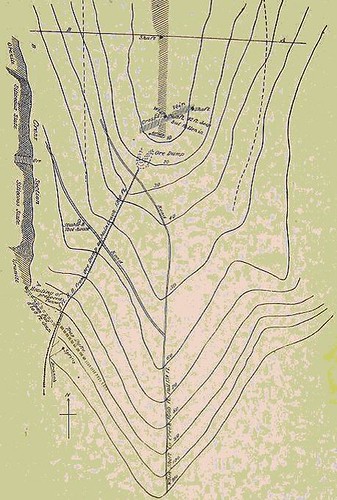

I recently came across this map of the Chapel Hill Iron Mine in an 1892 publication on mining in North Carolina. The Chapel Hill Iron Mine was operated by Gen. Robert F. Hoke, supposedly from about 1872-1882 and was a critical factor in how and where the rail line into Carrboro was built. Alternate connections to Durham, Hillsborough or Apex were considered, but connecting to University Station was the cheapest route and involved passing by Gen. Hoke's mine, so he put forward significant resources to make it come that way.

The map gives an interesting view into the workings of the mine. It shows the two main shafts (one of them already collapsed in 1892), which are now in the center of the Ironwoods neighborhood in Chapel Hill. I have previously found references (Orange County Observer, 10/23/1881) to a spur connecting from the rail line to the mine, but this map is the first time I have seen any indication of where it was. Apparently it went down the gully between Cardiff Place and Birchcrest Place. The 3’ gauge railroad must have wound back to the NW in order to connect with the main rail line without crossing Bolin Creek, so I suppose it must have followed a route like this:

The two red dots are supposed to be the locations of the shafts. I wonder if any remaining evidence of this narrow gauge railway can still be seen out there today?

UPDATE: Sure enough, we hiked up along the tracks just north of Bolin Creek and immediately found the abandoned grade. It looks like a good amount of work was involved in building up the grade for the spur and at least one small trestle must have been used. The spot where my gradual swooping curve takes a northward indentation was drawn to follow the contours on the topo map, but actually a trestle bridged that cove. In a couple of places, the OWASA sewer lines tore up the former railroad grade, but the grade is mostly intact and quite discernible.

Here's a picture of the historical marker at the top:

The map gives an interesting view into the workings of the mine. It shows the two main shafts (one of them already collapsed in 1892), which are now in the center of the Ironwoods neighborhood in Chapel Hill. I have previously found references (Orange County Observer, 10/23/1881) to a spur connecting from the rail line to the mine, but this map is the first time I have seen any indication of where it was. Apparently it went down the gully between Cardiff Place and Birchcrest Place. The 3’ gauge railroad must have wound back to the NW in order to connect with the main rail line without crossing Bolin Creek, so I suppose it must have followed a route like this:

The two red dots are supposed to be the locations of the shafts. I wonder if any remaining evidence of this narrow gauge railway can still be seen out there today?

UPDATE: Sure enough, we hiked up along the tracks just north of Bolin Creek and immediately found the abandoned grade. It looks like a good amount of work was involved in building up the grade for the spur and at least one small trestle must have been used. The spot where my gradual swooping curve takes a northward indentation was drawn to follow the contours on the topo map, but actually a trestle bridged that cove. In a couple of places, the OWASA sewer lines tore up the former railroad grade, but the grade is mostly intact and quite discernible.

Here's a picture of the historical marker at the top:

Sunday, September 6, 2009

Trespassers in the Alston Quarter

Here's a little bit of further interpretation on this map:

First, this map is redrafted from an earlier survey or surveys. It's not clear who made this, but I suggested it might be W. D. Bennet. David Southern says it might by Miles Philbeck. Either way, I do not know what document it is drawn from - it would be interesting to find that.

Second, the map shows parts of the land grants belonging to five different men:

Richard Everard (labeled Averett on the map),

Robert Forster,

John Lovwick (or Lovewick),

Edward Moseley,

George Moore,

and Lewis Conner.

Of these men, Moseley, Little and Lovwick were part of the surveying party that established the dividing line between North Carolina and Virginia in 1729. Many of those in the party were granted choice pieces of land in exchange for their service (it was a dangerous mission into the wilderness at the time). Moseley and Lovwick apparently chose parts of the highly desirable Haw Old Fields - lands traditionally settled by Native Americans, but more or less abandoned due to declining populations, disease, colonial pressure etc. Copies of Lovwick's grant and one of Moseley's are at the SHC at UNC and show taht they were granted by Lord John Carteret (later Lord Granville) in Nov. 1728 and reconveyed to George Burrington in 1730.

Richard Everard was the last Governor under the Lords Proprietor of North Carolina serving from 1725-1731. He is credited with initiating the NC-VA border survey (and little else). Everard evidently got a choice piece of the Haw Fields as well. His land passed to his grandson George Lathbury or Lashbury or Lashberry. Lathbury's 1o,000 acres passed to Edund Fanning, Abner Nash and Thomas Hart in 1770 for 670 Pounds, but only Nash's third was spared from confiscation following the Revolution (p. 45 2nd Report of the Ontario Archives, Alexander Fraser, 1904; State Records of NC, Vol 24, pg 285). Likely Sheriff John Butler wound up owning a part of the Everard tract. See Orange DB 3, pg 462.

This leaves the question of who Lewis Conner, Robert Forster and George Moore were. I am not sure who they were, but they were clearly all important folks in North Carolina around 1730.

George Moore (or Roger?) received this tract on 12 Nov. 1728. This land was later known as the Alston Quarter or Austin Quarter and over 1,000 acres of it is still in single ownership as a single lot. Moore's land apparently passed to a member of the Ashe family (a lawyer who was involved in the litigation over Strudwick's 30,000 acres - see below). The Ashe family included Gov. Samuel Ashe among many other notables. His grave is supposed to be there on the Alston Quarter (per Stockard's History of Alamance).

All of the tracts between Everhard's and Moore's, totalling almost 30,000 acres were somehow coveyed to Gov. George Burrington. This constituted all of the area that is now Hawfields, Saxapahaw and Swepsonville. Burrington tried to sell the Hawfields tracts several times including through an ad that ran in the Virginia Gazette 2/10/1738, a transcript of which is here:

http://www.ncpublications.com/colonial/Newspapers/subjects/Agri.htm#1736

Here are his descriptions of the five tracts [with my interpretations]:

1. The Tract of Land which was Mr. Robert Forrester’s, containing 2425 Acres. The first Tract lies between Sir Richard’s Land, and Marrowbone River.

[This is between the Everard-Lashbury tract and Back Creek - i.e. the area just upstream of Back Creek. Note that in one of the Land Grants in the SHC at UNC, it refers to neighboring property owner Robert Porter.]

2. The Tract of Land which was Mr. William Little’s, containing 4200 Acres. The second Tract lies between Marrow bone River, and Flat Branch; and has in it on the River, Saxapahaw, Low ground Run, and Indian Banch; and on Marrow-bone River, one Run or Branch. Flat Branch is opposite to the Entry of Arrunky River.

[Flat Branch is probably one of the creeks that flows into the Haw in Swepsonville, perhaps the one that flows almost immediately through the Virginia Mills site. Arrunky is clearly a mis-spelling of Aramanchey or Alamance. No real idea where Lowground Run or Indian Branch are, but he appears to mean that they are tributaries of the Haw directly. One Run – Lone Run? – is a tributary of Back Creek, but it is not clear which one, perhaps Mill Creek. Little's Tract includes the upper part of Swepsonville including the millsite.]

3. The Tract of Land which was Mr. John Lovick’s, containing 4200 Acres. The third Tract lies between Flat Branch and Buffelo Creek; and in it, on the said Saxapahaw River, is Dry Branch, and the Westward Indian Trading Path.

[The trading path apparently passed right through here and this would be consistent with maps which show the trading path crossing the Haw immediately upstream of Big Alamance Creek. Lovwick's Tract includes the lower part of the Town of Swepsonville and the Puryear Mill site.]

4. The Tract of Land which was Mr. Edward Moseley’s, containing 10000 Acres. The fourth Tract lies between Buffelo Creek, and Island Creek: At the South East Corner of the third Tract turns with an Elbow North, and passing by the East Ends of the first Three Tracts, terminates on the East Line of Sir Richard Everard’s; and is bounded on the East, with the afore mentioned Lands of Mr. Jones, and Major [James?] Pollock. In this Tract, are Jumping Run, Fish pond Branch, and the Pond; all on Saxapahaw River.

[Jumping Run is probably merely the east branch of Haw Creek, misinterpreted for a time as being a direct tributary of the Haw; no idea what the Fishpond Branch or the Pond were.]

5. The Tract of Land which was Mr. Edward Moseley’s, containing 8400 Acres. The fifth Tract lies between Island Creek [Meadow Creek], and Rocky Run, in a Sort of Triangle; and in it are Briery Creek [Motes Creek?], and Brick house Branch [Hobby Branch?].

[This is essentially the area just NW of the Alston Quarter and includes Saxapahaw and the Cedar Cliffs Mill.]

All of this land was sold by Gov. George Burrington to Samuel Strudwick per a deed recorded in the New Hanover County in 1754. When Strudwick came to America a decade later he discovered taht all sorts of folks had moved onto his land and commenced litigation (the map above apparently was a part of the litigation). It seems that the matter was not entirely resolved in Strudwick's favor. Some of the 'intruders' were there under color of title obtained from Granville's agents, who presumably did not really have a legitimate claim to the land since it was conveyed previously to the folks who were in Strudwick's chain of title. Nonetheless, a series of deeds from Strudwick appear to convey much of the land onward to Thompsons, Clendenins, Morrows, Millikans etc.

First, this map is redrafted from an earlier survey or surveys. It's not clear who made this, but I suggested it might be W. D. Bennet. David Southern says it might by Miles Philbeck. Either way, I do not know what document it is drawn from - it would be interesting to find that.

Second, the map shows parts of the land grants belonging to five different men:

Richard Everard (labeled Averett on the map),

Robert Forster,

John Lovwick (or Lovewick),

Edward Moseley,

George Moore,

and Lewis Conner.

Of these men, Moseley, Little and Lovwick were part of the surveying party that established the dividing line between North Carolina and Virginia in 1729. Many of those in the party were granted choice pieces of land in exchange for their service (it was a dangerous mission into the wilderness at the time). Moseley and Lovwick apparently chose parts of the highly desirable Haw Old Fields - lands traditionally settled by Native Americans, but more or less abandoned due to declining populations, disease, colonial pressure etc. Copies of Lovwick's grant and one of Moseley's are at the SHC at UNC and show taht they were granted by Lord John Carteret (later Lord Granville) in Nov. 1728 and reconveyed to George Burrington in 1730.

Richard Everard was the last Governor under the Lords Proprietor of North Carolina serving from 1725-1731. He is credited with initiating the NC-VA border survey (and little else). Everard evidently got a choice piece of the Haw Fields as well. His land passed to his grandson George Lathbury or Lashbury or Lashberry. Lathbury's 1o,000 acres passed to Edund Fanning, Abner Nash and Thomas Hart in 1770 for 670 Pounds, but only Nash's third was spared from confiscation following the Revolution (p. 45 2nd Report of the Ontario Archives, Alexander Fraser, 1904; State Records of NC, Vol 24, pg 285). Likely Sheriff John Butler wound up owning a part of the Everard tract. See Orange DB 3, pg 462.

This leaves the question of who Lewis Conner, Robert Forster and George Moore were. I am not sure who they were, but they were clearly all important folks in North Carolina around 1730.

George Moore (or Roger?) received this tract on 12 Nov. 1728. This land was later known as the Alston Quarter or Austin Quarter and over 1,000 acres of it is still in single ownership as a single lot. Moore's land apparently passed to a member of the Ashe family (a lawyer who was involved in the litigation over Strudwick's 30,000 acres - see below). The Ashe family included Gov. Samuel Ashe among many other notables. His grave is supposed to be there on the Alston Quarter (per Stockard's History of Alamance).

All of the tracts between Everhard's and Moore's, totalling almost 30,000 acres were somehow coveyed to Gov. George Burrington. This constituted all of the area that is now Hawfields, Saxapahaw and Swepsonville. Burrington tried to sell the Hawfields tracts several times including through an ad that ran in the Virginia Gazette 2/10/1738, a transcript of which is here:

http://www.ncpublications.com/colonial/Newspapers/subjects/Agri.htm#1736

Here are his descriptions of the five tracts [with my interpretations]:

1. The Tract of Land which was Mr. Robert Forrester’s, containing 2425 Acres. The first Tract lies between Sir Richard’s Land, and Marrowbone River.

[This is between the Everard-Lashbury tract and Back Creek - i.e. the area just upstream of Back Creek. Note that in one of the Land Grants in the SHC at UNC, it refers to neighboring property owner Robert Porter.]

2. The Tract of Land which was Mr. William Little’s, containing 4200 Acres. The second Tract lies between Marrow bone River, and Flat Branch; and has in it on the River, Saxapahaw, Low ground Run, and Indian Banch; and on Marrow-bone River, one Run or Branch. Flat Branch is opposite to the Entry of Arrunky River.

[Flat Branch is probably one of the creeks that flows into the Haw in Swepsonville, perhaps the one that flows almost immediately through the Virginia Mills site. Arrunky is clearly a mis-spelling of Aramanchey or Alamance. No real idea where Lowground Run or Indian Branch are, but he appears to mean that they are tributaries of the Haw directly. One Run – Lone Run? – is a tributary of Back Creek, but it is not clear which one, perhaps Mill Creek. Little's Tract includes the upper part of Swepsonville including the millsite.]

3. The Tract of Land which was Mr. John Lovick’s, containing 4200 Acres. The third Tract lies between Flat Branch and Buffelo Creek; and in it, on the said Saxapahaw River, is Dry Branch, and the Westward Indian Trading Path.

[The trading path apparently passed right through here and this would be consistent with maps which show the trading path crossing the Haw immediately upstream of Big Alamance Creek. Lovwick's Tract includes the lower part of the Town of Swepsonville and the Puryear Mill site.]

4. The Tract of Land which was Mr. Edward Moseley’s, containing 10000 Acres. The fourth Tract lies between Buffelo Creek, and Island Creek: At the South East Corner of the third Tract turns with an Elbow North, and passing by the East Ends of the first Three Tracts, terminates on the East Line of Sir Richard Everard’s; and is bounded on the East, with the afore mentioned Lands of Mr. Jones, and Major [James?] Pollock. In this Tract, are Jumping Run, Fish pond Branch, and the Pond; all on Saxapahaw River.

[Jumping Run is probably merely the east branch of Haw Creek, misinterpreted for a time as being a direct tributary of the Haw; no idea what the Fishpond Branch or the Pond were.]

5. The Tract of Land which was Mr. Edward Moseley’s, containing 8400 Acres. The fifth Tract lies between Island Creek [Meadow Creek], and Rocky Run, in a Sort of Triangle; and in it are Briery Creek [Motes Creek?], and Brick house Branch [Hobby Branch?].

[This is essentially the area just NW of the Alston Quarter and includes Saxapahaw and the Cedar Cliffs Mill.]

All of this land was sold by Gov. George Burrington to Samuel Strudwick per a deed recorded in the New Hanover County in 1754. When Strudwick came to America a decade later he discovered taht all sorts of folks had moved onto his land and commenced litigation (the map above apparently was a part of the litigation). It seems that the matter was not entirely resolved in Strudwick's favor. Some of the 'intruders' were there under color of title obtained from Granville's agents, who presumably did not really have a legitimate claim to the land since it was conveyed previously to the folks who were in Strudwick's chain of title. Nonetheless, a series of deeds from Strudwick appear to convey much of the land onward to Thompsons, Clendenins, Morrows, Millikans etc.

Thursday, September 3, 2009

Marrowbone and Buffalo

A recent email to David Southern:

Here are two other maps that show Back Creek and Haw Creek. You have probably seen them both before. One is Jeffreys 1775 map of VA with northern part of NC. The other is a transcipt of some old document probably done by W. D. Bennett. Taken together these two maps and the one you mailed clearly show that Back Creek's old name was Marrowbone River. They also show that Haw Creek was once Buffalo(e) Creek/Branch.

The Jeffreys Map (1775).

Jeffreys shows Jumping Run right below Haw Creek/Buffalo Branch, but that appears to be an error. It seems likely that Jumping Run is actually the east branch of Haw Creek and some surveyor assumed that it flowed into the Haw River on its own. New River, shown at the bottom of Jeffreys, is of course Cane Creek. But Jeffreys also shows some major errors such as the location of the Haw-Alamance confluence and far worse, he has the Neuse River flowing almost due south from the mouth of the Little River. But Eno, Little and Flat are basically correct. McGowan's Creek is shown as Wadcush River, which is a name I have heard before.

Meanwhile, the 1763 plat shows Island Creek just below Haw/Buffalo Creek. Island Creek appears to be Meadow Creek. Below that is Rockey Run, which from its position on the map would seem to be near Motes Creek. The 1893 Spoon Map of Alamance shows Rocky Run as the first tributary from the east immediately below Motes Creek. On the 1763 plat, Cane Creek is clearly doubly labeled as also being New River.

The 1763 Plat

So, here's the conclusion

Back Creek was definitely Marrowbone River.

Haw Creek was definitely Buffalo Creek (cf ODB 4, pg 290).

The eastern fork of Haw Creek was probably Jumping Run.

Meadow Creek was probably once Island Creek.

Rockey Run is still the name of the first tributary on the east below Motes Creek.

Cane Creek was definitely New River.

I am not sure there is any new information there, but I thought I would write it down so that it could at least be corrected if some of it is wrong. Please let me know if that matches your interpretation.

LATE UPDATE:

There are at least two more maps of the area that rea notable. First,

The 1737 Cowley-Moseley map shows Marrowbone River, Buffalo Creek, Jumping Run, New River, Wadcush Creek and Aramanchy River, just about as Jeffreys did 38 years later (no doubt copied). Moseley was one of the original land grantees in the Haw Fields as compensation for his role in surveying the VA/NC border. No wonder then that he shows so much detail in the vicinty of Haw Fields.

The second map is from 1747:

This map does not label the streams near the Haw Fields, but it does show them in quite some detail and almost identically to the Crowley-Moseley map.

Here are two other maps that show Back Creek and Haw Creek. You have probably seen them both before. One is Jeffreys 1775 map of VA with northern part of NC. The other is a transcipt of some old document probably done by W. D. Bennett. Taken together these two maps and the one you mailed clearly show that Back Creek's old name was Marrowbone River. They also show that Haw Creek was once Buffalo(e) Creek/Branch.

The Jeffreys Map (1775).

Jeffreys shows Jumping Run right below Haw Creek/Buffalo Branch, but that appears to be an error. It seems likely that Jumping Run is actually the east branch of Haw Creek and some surveyor assumed that it flowed into the Haw River on its own. New River, shown at the bottom of Jeffreys, is of course Cane Creek. But Jeffreys also shows some major errors such as the location of the Haw-Alamance confluence and far worse, he has the Neuse River flowing almost due south from the mouth of the Little River. But Eno, Little and Flat are basically correct. McGowan's Creek is shown as Wadcush River, which is a name I have heard before.

Meanwhile, the 1763 plat shows Island Creek just below Haw/Buffalo Creek. Island Creek appears to be Meadow Creek. Below that is Rockey Run, which from its position on the map would seem to be near Motes Creek. The 1893 Spoon Map of Alamance shows Rocky Run as the first tributary from the east immediately below Motes Creek. On the 1763 plat, Cane Creek is clearly doubly labeled as also being New River.

The 1763 Plat

So, here's the conclusion

Back Creek was definitely Marrowbone River.

Haw Creek was definitely Buffalo Creek (cf ODB 4, pg 290).

The eastern fork of Haw Creek was probably Jumping Run.

Meadow Creek was probably once Island Creek.

Rockey Run is still the name of the first tributary on the east below Motes Creek.

Cane Creek was definitely New River.

I am not sure there is any new information there, but I thought I would write it down so that it could at least be corrected if some of it is wrong. Please let me know if that matches your interpretation.

LATE UPDATE:

There are at least two more maps of the area that rea notable. First,

The 1737 Cowley-Moseley map shows Marrowbone River, Buffalo Creek, Jumping Run, New River, Wadcush Creek and Aramanchy River, just about as Jeffreys did 38 years later (no doubt copied). Moseley was one of the original land grantees in the Haw Fields as compensation for his role in surveying the VA/NC border. No wonder then that he shows so much detail in the vicinty of Haw Fields.

The second map is from 1747:

This map does not label the streams near the Haw Fields, but it does show them in quite some detail and almost identically to the Crowley-Moseley map.

Thursday, August 27, 2009

Lucy Worth Jackson

Steve Rankin sent me an interesting article about female map makers of the 19th century. It reminded me of an additional local example: Lucy Worth Jackson. Ms. Jackson's husband was a miner, or maybe more like mineral speculator, who owned a coal mine near Carbonton in Chatham County and also a "gold mine" on Cane creek in what is now Alamance County, then considered Chatham.

Ms. Jackson made at least two beautiful color maps of areas in Chatham County:

Map of the Coalfields of Chatham and a Portion of the Mineral Region of N. C., circa 1874

Map of Cane Creek Gold Mines, Chatham County, North Carolina, circa 1878

Copies of the first map above can be purchased inexpensively from http://chathamhistory.org/publications.html

The second map is posted on the NC Maps site: http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/ncmaps&CISOPTR=2384&CISOBOX=1&REC=6

Lucy Worth Jackson was the daughter of Gov. Jonathan Worth.

Ms. Jackson made at least two beautiful color maps of areas in Chatham County:

Map of the Coalfields of Chatham and a Portion of the Mineral Region of N. C., circa 1874

Map of Cane Creek Gold Mines, Chatham County, North Carolina, circa 1878

Copies of the first map above can be purchased inexpensively from http://chathamhistory.org/publications.html

The second map is posted on the NC Maps site: http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/ncmaps&CISOPTR=2384&CISOBOX=1&REC=6

Lucy Worth Jackson was the daughter of Gov. Jonathan Worth.

Sunday, August 2, 2009

The Occupation of Chapel Hill, April, 1865

14 April 1865

On April 14, 1865, Confederate General Joseph Wheeler's Cavalry arrived near Chapel Hill, fleeing Sherman’s Army which occupied Raleigh the same day. Wheeler had fought a rearguard battle the previous day at Morrisville and a small skirmish occurred at the Atkins farm on New Hope Creek on the evening of the 14th.

Wheeler’s men had a reputation of appropriating property and many in Chapel Hill were worried about their possessions as well as the University’s. Lt. James Coffin (UNC Class of 1859) was among the men who arrived with Wheeler and is credited with helping ensure that the village and University were largely unscathed. Some of the men were sent to meet with UNC President Swain, but Swain was off negotiating the surrender of Raleigh in exchange for the protection of the government buildings. Swain left Math Professor Charles Phillips in charge.

General Wheeler set up his command post across the street from the Chapel of the Cross on Franklin Street. Although no history directly records it, apparently Wheeler ordered his men to dig rifle pits to guard the approach to the village along what is now South Road. Battle obliquely mentions this in describing hikes around Chapel Hill: “to the south of [Gimghoul Castle] . . . a winding, rocky path . . . leads by the rifle pits dug by Wheeler's Cavalry as they retreated . . . ”

15 April 1865

The next day he had charge of the rearguard and cleared the town of all stragglers. Wheeler’s men were in bad shape and word of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House left the Confederates very demoralized. It was raining “in torrents” on the 15th according to Gen. Sherman’s letter of that date to Gen. Grant

Wheeler wrote in The War of the Rebellion: “On the 14th I moved on to Chapel Hill, and on the 15th the enemy approached but after firing a few shots without effect again retired. Pursuant to orders I now moved my command back of Chapel Hill, with orders not to engage the enemy unless attacked.”

16 April 1865

General Wheeler prepared to retreat further on April 16, Easter Sunday. The Confederate Army left, according to Cornelia Phillips Spencer, at 2 PM: “A few hours of absolute and Sabbath stillness and silence ensued. The groves stood thick and solemn, the bright sun shining through the great boles and down the grassy slopes, while a pleasant fragrance was wafted from the purple panicles of the Paulownias.”

Cornelia Phillips Spencer's The Last Ninety Days of the War in North Carolina relates: "We sat in our pleasant piazzas and awaited events with quiet resignation. Our silver had all been buried. There was not much provision to be carried off. The sight of our empty store-rooms and smoke-houses would be likely to move our invaders to laughter. But there was anxiety as to the fate of the University buildings, libraries and portraits.”

Toward the end of the day, the Union Army arrived and a delegation led by President Swain (who had returned on the 15th) went out to meet the first Union officer to discuss the protection of the village and campus. The Union officer reassured them and Pres. Swain told them that all of the Confederate Army had left. The officer retired to the Union camp somewhat east of Chapel Hill.

In his Recollections of a Civil War Cavalryman, Union General William Douglas Hamilton says: “I was ordered to proceed next day to Chapel Hill . . . The next day we moved eight miles into Chapel Hill. I established headquarters in a house on the outskirts of the town, and camped the command in a grove near by.” This was probably near the Gimghoul neighborhood.

17 April 1865

Kemp Plummer Battle's History of the University of North Carolina says: “About eight o'clock the next day, the 17th, General Smith B. Atkins, of Freeport, Illinois, with four thousand cavalry, took possession of the town.” Spencer adds: “General Sherman's orders were obeyed, and all the dwellings in the town, as well as the University property, were well guarded. The soldiers detailed for this purpose from the 9th Michigan Cavalry were especially noted for civility and propriety.”

“The persistency of President Swain in keeping up the exercises of the institution was evident from the fact that when the Federal troops took possession of the village there were about a dozen students, mostly residents of Chapel Hill, on hand to witness the novel spectacle.”

19 April 1865

On April 19, 1865, Pres. Swain wrote to General Sherman to the effect that both the Confederate and Union Armies had taken all the food and horses in the area. Battle tell us: “Many families outside the village had been stripped of the means of subsistence, among them a Baptist preacher, Rev. Dr. [George W.] Purefoy, who had a family, white and colored, of over fifty persons, with no provisions and not a horse or mule. He hoped that the General would relax the severity of his orders, and believed that General Atkins would welcome the change."

22 April 1865

General Sherman replied on the 22nd that as soon as war should cease, "seizure of horses and private property will cease. Some animals for the use of the farmers may then be spared. As soon as peace comes the Federals will be the friends of the farmers and working classes, as well as actual patrons of churches, colleges, asylums and institutions of learning and charity."

Battle asserts: "This correspondence shows that, away from places where guards were posted as an especial favor, plundering of the country people was allowed by the military authorities over ten days after Lee's surrender. There was much robbery, too, by stragglers and other unauthorized men, called "Bummers." Outrages to females were forbidden, and the orders were obeyed. I heard of no burning of houses in this part of the world traceable to the soldiers."

Battle says: "It was during the time that General Atkins was stationed at Chapel Hill that he wooed and won Eleanor, the beautiful daughter of President Swain. The General ingratiated himself with our people by his fairness and courtesy. He was a man of fine appearance and of high character, the editor of an influential paper in Freeport. Still the people living in the line of Sherman's march, who had suffered much by the plundering of his army, could not forget that Atkin's brigade was a part of it, and heard of the match with disapproval. It distinctly weakened the President's popularity, though he never seemed to realize the loss."

29 April 1865

Hamilton writes: “On April 29th, General Kilpatrick came to Chapel Hill from Durham’s Station and reviewed the brigade for the last time. On May 3rd, we bid farewell to Chapel Hill and marched twelve miles to Hillsboro.” Thus ended the 20 days when armies occupied Chapel Hill.

On April 14, 1865, Confederate General Joseph Wheeler's Cavalry arrived near Chapel Hill, fleeing Sherman’s Army which occupied Raleigh the same day. Wheeler had fought a rearguard battle the previous day at Morrisville and a small skirmish occurred at the Atkins farm on New Hope Creek on the evening of the 14th.

Wheeler’s men had a reputation of appropriating property and many in Chapel Hill were worried about their possessions as well as the University’s. Lt. James Coffin (UNC Class of 1859) was among the men who arrived with Wheeler and is credited with helping ensure that the village and University were largely unscathed. Some of the men were sent to meet with UNC President Swain, but Swain was off negotiating the surrender of Raleigh in exchange for the protection of the government buildings. Swain left Math Professor Charles Phillips in charge.

General Wheeler set up his command post across the street from the Chapel of the Cross on Franklin Street. Although no history directly records it, apparently Wheeler ordered his men to dig rifle pits to guard the approach to the village along what is now South Road. Battle obliquely mentions this in describing hikes around Chapel Hill: “to the south of [Gimghoul Castle] . . . a winding, rocky path . . . leads by the rifle pits dug by Wheeler's Cavalry as they retreated . . . ”

15 April 1865

The next day he had charge of the rearguard and cleared the town of all stragglers. Wheeler’s men were in bad shape and word of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House left the Confederates very demoralized. It was raining “in torrents” on the 15th according to Gen. Sherman’s letter of that date to Gen. Grant

Wheeler wrote in The War of the Rebellion: “On the 14th I moved on to Chapel Hill, and on the 15th the enemy approached but after firing a few shots without effect again retired. Pursuant to orders I now moved my command back of Chapel Hill, with orders not to engage the enemy unless attacked.”

16 April 1865

General Wheeler prepared to retreat further on April 16, Easter Sunday. The Confederate Army left, according to Cornelia Phillips Spencer, at 2 PM: “A few hours of absolute and Sabbath stillness and silence ensued. The groves stood thick and solemn, the bright sun shining through the great boles and down the grassy slopes, while a pleasant fragrance was wafted from the purple panicles of the Paulownias.”

Cornelia Phillips Spencer's The Last Ninety Days of the War in North Carolina relates: "We sat in our pleasant piazzas and awaited events with quiet resignation. Our silver had all been buried. There was not much provision to be carried off. The sight of our empty store-rooms and smoke-houses would be likely to move our invaders to laughter. But there was anxiety as to the fate of the University buildings, libraries and portraits.”

Toward the end of the day, the Union Army arrived and a delegation led by President Swain (who had returned on the 15th) went out to meet the first Union officer to discuss the protection of the village and campus. The Union officer reassured them and Pres. Swain told them that all of the Confederate Army had left. The officer retired to the Union camp somewhat east of Chapel Hill.

In his Recollections of a Civil War Cavalryman, Union General William Douglas Hamilton says: “I was ordered to proceed next day to Chapel Hill . . . The next day we moved eight miles into Chapel Hill. I established headquarters in a house on the outskirts of the town, and camped the command in a grove near by.” This was probably near the Gimghoul neighborhood.

17 April 1865

Kemp Plummer Battle's History of the University of North Carolina says: “About eight o'clock the next day, the 17th, General Smith B. Atkins, of Freeport, Illinois, with four thousand cavalry, took possession of the town.” Spencer adds: “General Sherman's orders were obeyed, and all the dwellings in the town, as well as the University property, were well guarded. The soldiers detailed for this purpose from the 9th Michigan Cavalry were especially noted for civility and propriety.”

“The persistency of President Swain in keeping up the exercises of the institution was evident from the fact that when the Federal troops took possession of the village there were about a dozen students, mostly residents of Chapel Hill, on hand to witness the novel spectacle.”

19 April 1865

On April 19, 1865, Pres. Swain wrote to General Sherman to the effect that both the Confederate and Union Armies had taken all the food and horses in the area. Battle tell us: “Many families outside the village had been stripped of the means of subsistence, among them a Baptist preacher, Rev. Dr. [George W.] Purefoy, who had a family, white and colored, of over fifty persons, with no provisions and not a horse or mule. He hoped that the General would relax the severity of his orders, and believed that General Atkins would welcome the change."

22 April 1865

General Sherman replied on the 22nd that as soon as war should cease, "seizure of horses and private property will cease. Some animals for the use of the farmers may then be spared. As soon as peace comes the Federals will be the friends of the farmers and working classes, as well as actual patrons of churches, colleges, asylums and institutions of learning and charity."

Battle asserts: "This correspondence shows that, away from places where guards were posted as an especial favor, plundering of the country people was allowed by the military authorities over ten days after Lee's surrender. There was much robbery, too, by stragglers and other unauthorized men, called "Bummers." Outrages to females were forbidden, and the orders were obeyed. I heard of no burning of houses in this part of the world traceable to the soldiers."

Battle says: "It was during the time that General Atkins was stationed at Chapel Hill that he wooed and won Eleanor, the beautiful daughter of President Swain. The General ingratiated himself with our people by his fairness and courtesy. He was a man of fine appearance and of high character, the editor of an influential paper in Freeport. Still the people living in the line of Sherman's march, who had suffered much by the plundering of his army, could not forget that Atkin's brigade was a part of it, and heard of the match with disapproval. It distinctly weakened the President's popularity, though he never seemed to realize the loss."

29 April 1865

Hamilton writes: “On April 29th, General Kilpatrick came to Chapel Hill from Durham’s Station and reviewed the brigade for the last time. On May 3rd, we bid farewell to Chapel Hill and marched twelve miles to Hillsboro.” Thus ended the 20 days when armies occupied Chapel Hill.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)