North Carolina Journal of Law (Vol 1, pp 516-518 , 1904):

“Let the man have been tarred with the University stick and he will tell you along with his after-dinner cigar that he has a notion of some day building a house at Chapel Hill – and there remaining to the end of the chapter in the one place where he believes he can obtain a large and perfect peace. There men cling to the town and its surroudnigns with a memory that is both tenacious and jealous of details.

“A friend was describing to one of these - a graduate before the war – the site of the present Alumni Building. Suddenly the old graduate’s eyes flashed fire:

“ ‘What!’ he exclaimed. 'You don’t tell me they’ve cut down the old college linden! I’d rather they’d have gone without that building forever than that they should have touched that tree!

“And so it goes. Living in the hearts of its scattered children, each tree shrub and rose bush, almost each stone of its serried ranks of rough built walls, bears its own faint story; and it is the indefinable suggestion that seems in time to float out from the inanitmate things that have brushed on human hopes that strangely strikes the newcomer at the moment he places foot upon the campus and brings to the returned a tingling of the blood and a half forgotten smell of the air that at once exhilirate and recall to half sad dreams of byegone days.

“As the shock of death precedes Nirvana, so does one’s abrupt alightment at University Station chill the heart before the delight of his journey’s end. Here you are ona train that comes dashing with a 20th century roar around a curve at forty miles an hour. The coach is full of people – quick, nervous looking people, all with the traveling face, talking, reading papers and magazines, blinking at the dust and cinders that swirl in the windows and doors in the wake of the engine’s panting stress of speed. A cord is pulled, the great train quivers and stopes. You grab your bag and somehow instinctively hurry to the door with a vague idea that you are impeding commerce do you delay. You alight, a bell rings and you see the rear coach disappearing ina cloud of dust around another curve and you find yourself facing two dingy country stores, a more dingy station and half a dozen loose jointed men who, with their hands in their pockets, stand gleaning their last excitement of the day in a vague regard of the curve in the track around which your train has vanished from sight. The transition from the histle of modern travel to the apathy of a country place so small as to defy the ordinary expressions of limitation is numbing; village or handlet would exaggerate University – it is a spot and nothing more, except that the fates of railroad engineering have made it the gate at the end of the present day to the world of Chapel Hill.

“But now there is the clanking of a bell that echoes strangely against the dead, dull air of “University” and the “Chapel Hill Limited” – three freight cars, an engine and one coach that contains in itself the three compartments of first class, “Jim Crow” and baggage “cars” – bucks lazily down from the water tank up the road. Six or seven people climb aboard, a trunk is hoisted into the “baggage car,” and the “captain” waves his hand, the citizens of the Station turn and stare moodily and the Limited sets out for its ten mile run to its destination. I use the word “Limited: advisedly, but the limit is not in time but on speed; it is against the rule to go the ten miles in less than forty minutes. On a fair evening or a fresh morning, the run is a delightful one, if time be not – as it generally is not – of the essence. The track winds along among the hills like a serpent – hills that are full of timber and tangled brush and vivid with color – through close sweeping woods that are redolent of sweet odors, past tall stemmed flowers that invade the windows as we pass, over bridges which span shallow streams that bubble over scattered boulders, flushing rabbits and quail and squirrels that flee perfunctorily from the easy going train and stop to look back with the habit of curiosity with which one regards the passing even of an old friend, past fields and widely separated huts of log and mud surrounded by groves that would grace a mansion, and, so, slowly, onward, the wheels crying weirdly over the ungreased curves, the occasional wanton shriek of the whistle rattling among the oaks of the hilltop or bellowing down the coiling recesses of the gorge. And gradually, from the ‘jumping off place’ of University, there comes an ever deepening spell of the unreal that merges at length into the sane but peculiar world of Chapel Hill.

“This connecting link, with its engine and its solitary coach, is a story in itself, that has ere this done service of its two columns of facetiousness in many a large paper of the North. But far be it from me to treat anything that leads to Chapel Hill facetiously – much less the University train. I felt somewhat like the gentleman of the linden when it fot a coal burning engine, and when a man like ‘Capt.’ Smith stops by the roadside as he did yesterday to deliver a bundle and get in a jub of sweet cider from the apple orchard on the hill, it is nobody’s business but his own. ‘Capt.’ Smith and ‘Capt.’ Sparrow have been with the road since it started and it wouldn’t be the road it is without them. There was once upon a time a Capt. Guthrie, also, but he had the heart of an adventurer and went out into the world – to Hillsboro. It is a ‘great’ road and it leads to a ‘great’ place.”

- R. L. Gray in the News and Observer

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

The [Piper] Donation

UNC's original property was donated to the University by Chapel Hill area land owners who thought that having a University around here would bring property values up (a point upon which they have been suitably vindicated). One of the original donors was Alexander Piper J-a-m-e-s-P-a-t-t-e-r-s-o-n [Update: Piper, not Patterson], who gave (among other things) a tract of land about a mile west of what became the main campus. [Correction: I do not find any record of Patterson donating land; the Daniel map reads "Donation Patterson." Further Update: I think maybe it says "Donation Piper 20 ac." I think this refers to the deed from Alexander Piper to UNC recorded at ODB 5, pg 614.]

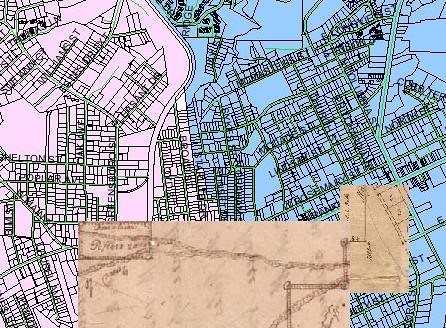

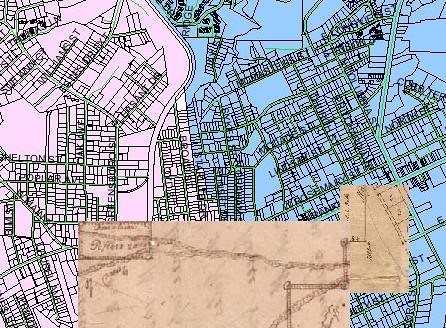

I got to wondering just where the Piper Donation was. I made a bit of a mash up of the 1817 Plan of Chapel Hill, the 1792 Daniel Map of UNC, and the 2009 Orange County GIS tax maps, tying together the dog leg western boundary of the campus, the lots at the corner of Franklin and Columbia Street and the position of the Patterson Donation shown on the Daniel map. The result is very interesting.

The Piper Donation was what would later become Downtown Carrboro:

The tract appears to have run from the rail line on the east to Oak Avenue on the west and from Weaver Street south to the south edge of the lots along Main Street. In other words, some pretty nice real estate by modern standards.

Of course, back in 1792, there was not that much there in terms of development. Two roads ran through the property. The north fork was essentially what is now Weaver Street, turning northward and following Main Street, and then Hillsborough Road to Hillsborough. The south fork led to McCauley's Mill, a grist mill that stood about where University Lake dam is now; no modern road really tracks this course.

You will commonly hear it said that Carrboro grew up where it did because that is where the railhead was - that is, the rail lines didn't used to continue south of Main Street. So a railroad station was built and a grist mill and other industries grew up around the railhead. That area came to be called West End (of Chapel Hill) and was eventually incorporated into the Town of Venable, soon renamed Carrboro after the owner of the big hosiery mill.

But it appears that the railhead was probably located in that spot because it was the edge of the Piper Donation. UNC owned the land, and they must have agreed to have the rail line come to that point. Or so it appears.

I got to wondering just where the Piper Donation was. I made a bit of a mash up of the 1817 Plan of Chapel Hill, the 1792 Daniel Map of UNC, and the 2009 Orange County GIS tax maps, tying together the dog leg western boundary of the campus, the lots at the corner of Franklin and Columbia Street and the position of the Patterson Donation shown on the Daniel map. The result is very interesting.

The Piper Donation was what would later become Downtown Carrboro:

The tract appears to have run from the rail line on the east to Oak Avenue on the west and from Weaver Street south to the south edge of the lots along Main Street. In other words, some pretty nice real estate by modern standards.

Of course, back in 1792, there was not that much there in terms of development. Two roads ran through the property. The north fork was essentially what is now Weaver Street, turning northward and following Main Street, and then Hillsborough Road to Hillsborough. The south fork led to McCauley's Mill, a grist mill that stood about where University Lake dam is now; no modern road really tracks this course.

You will commonly hear it said that Carrboro grew up where it did because that is where the railhead was - that is, the rail lines didn't used to continue south of Main Street. So a railroad station was built and a grist mill and other industries grew up around the railhead. That area came to be called West End (of Chapel Hill) and was eventually incorporated into the Town of Venable, soon renamed Carrboro after the owner of the big hosiery mill.

But it appears that the railhead was probably located in that spot because it was the edge of the Piper Donation. UNC owned the land, and they must have agreed to have the rail line come to that point. Or so it appears.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)