This afternoon, I want to tell you the story of the historical landscape of Carrboro, but while doing so, I will have to address the historical landscape of Chapel Hill. So let’s begin right here where I am standing.

Before Carrboro, before Chapel Hill, before UNC, before the State of North Carolina, there was a chapel - an Anglican chapel of ease, which was a respite for travellers. It was called New Hope Chapel, after the creek into whose waters it drained. One of the first state land grants in Orange County was to Mark Morgan for the "Chapel Tract," so the chapel was definitely built before 1778 - probably during the administration of colonial Governor Gabriel Johnston. In any case, the chapel was where the south end of the Carolina Inn is now.

Mark Morgan's Chapel Tract was soon divided up and sold to a handful of local farmers. In 1792, UNC's original campus was donated to the University by these same Chapel Hill area farmers who thought that having a University around here would bring property values up (a point upon which they have been suitably vindicated). One of the donors was Kit Barbee and I am standing on the land he gave right now as I give this talk. Other donors gave parcels that were nearby but not contiguous, for example the seldom noted Alexander Piper, who gave a 20 acre tract of land about a mile west of what became UNC (ODB 5, pg 614).

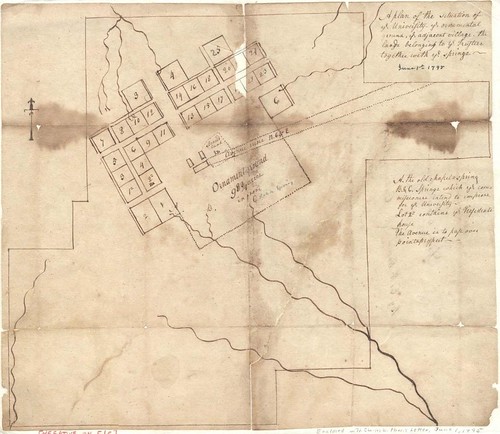

Piper’s grant is shown plainly on the 1792 Daniel map of UNC's lands, the first detailed map of this area. The second map of this area is the 1795 Plan of the Situation of Ye University, which is the oldest existing map showing the location of the streets in Chapel Hill. Here is the intersection of Franklin and Columbia.

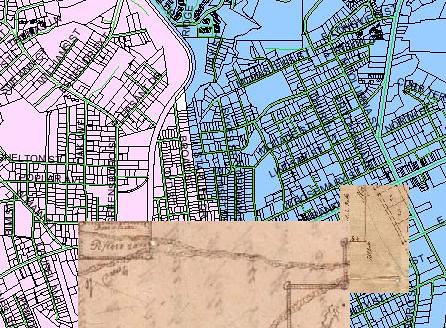

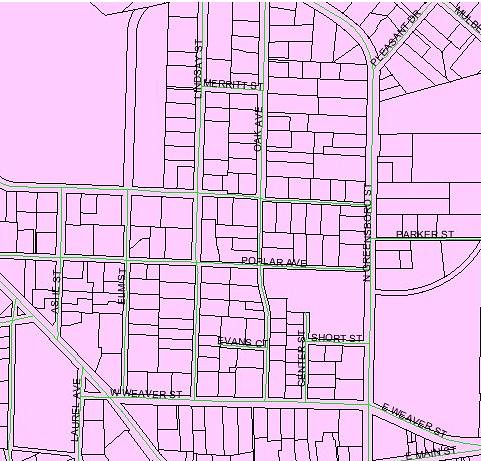

I got to wondering just where the Piper Donation was, so I made a bit of a mash up of the 1795 Plan of the Situation, the 1792 Daniel Map, and the 2009 Orange County GIS tax maps, tying together the dog leg western boundary of the campus, the lots at the corner of Franklin and Columbia Street and the position of the Patterson Donation shown on the Daniel map. The result is very interesting:

The Piper Donation was what would later become Downtown Carrboro. The tract appears to have run from the rail line on the east to Oak Avenue on the west and from Weaver Street south to the south edge of the lots along Main Street. The Orange Co Tax Assessor currently values the Piper Donation at about $20 Million.

![6 Piper_Donation[1]](http://farm3.static.flickr.com/2689/4297026797_9c832c9ea1.jpg)

Of course, back in 1792, there was not that much there in terms of development. Two roads ran through the property. The north fork was essentially what is now Weaver Street, turning northward and following Main Street, and then Hillsborough Road to Hillsborough. The south fork led to McCauley's Mill, a grist mill that stood about where University Lake dam is now; no modern road really tracks that course.

UNC sold off this future $20 Million in real estate in 1837 to John M Craig for $40 (ODB 28, pg 272). Thirty years later, Craig's estate sold a larger parcel to William L Saunders – apparently the same vicinity: "lying on the western outskirts of Chapel Hill upon both sides of the road leading from Chapel Hill to Greensboro adjoining the lands of John Weaver, Thomas Weaver, and others and bounded as follows: Beginning at the mud hole in Craigs Lane upon said Road running thence . . . to a locust on the road leading to Greensboro [now North Greensboro Street] then . . . to a rock in the road from Chapel Hill to Jones Ford on Haw River [Jones Ferry Road] thence E with the said Road” (ODB 39, pg 312). Saunders sold exactly the same property to Chapel Hill merchants Henry H Patterson and Fendal S Hogan in 1879 (ODB 46, pg 257). That 101 ½ acres became most of downtown Carrboro.

The Railroad

Notably, 1879 was quite a propitious year in which to have bought that land, as the State University Rail Road was just getting reorganized and preparing to actually build a rail line this time around – which they actually completed in 1882. In the middle of Patterson’s 101 ½ acres was where the rail line terminated – right where it reached the road leading to Hillsborough, Greensboro, and points westward. That extension of Rosemary Street in Chapel Hill, the street at which the railhead stopped, came to be called Main Street.

You will commonly hear it said that Carrboro grew up where it did because the railroad was prohibited from coming within one mile of the University campus. That is not correct. There was no statute from the Legislature nor any corporate charter provision nor any decision of the UNC Board of Trustees requiring that the railhead keep away from the campus. Quite the reverse of the claims of some, the Trustees were not at all shy about the railroad; they lobbied the legislature to get the use of convict labor for construction. And it appears that the project needed cheap labor as it was seriously underfunded and only barely got built.

Various alternative routes were considered in 1879 and the most promising two were the route that was actually built from Carrboro to University Station on the North Carolina Railroad and a route that would have run more or less along what is now 15-501 to the rail line in Durham. It is interesting to contemplate for a moment how different our community would be if that rail line had been built to Durham. However, the line to Durham was more expensive; without adequate investment from Durham businessmen, the shorter and cheaper route to University Station had to be used. Gen. Hoke's iron mine offered to provide the steel, which sealed the deal for the route that came by the iron mine to the west end of Chapel Hill.

That iron mine is now the Ironwoods neighborhood in Chapel Hill.

Durham industrialist and UNC benefactor Julian Shakespeare Carr was bitterly opposed to the route to University Station.

Carr wanted the line to come to Durham, but could not convince enough of his business associates in Durham to invest in the project. Carr wrote a letter to The Chapel Hill Ledger (1/24/1880) casting doubt on the success of a route that did not connect at Durham: “I trust that your railroad to University Station may prove of as much benefit to the good people of Chapel Hill as some of your very clever citizens seem to think it will, but, to be honest with you, I have very little hope of it myself.” As it turned out, the railroad to University Station was not only a benefit to “the good people of Chapel Hill,” but it was so successful that it spawned a new town that would, thirty-three years later, be named after Julian Shakespeare Carr.

Twice during construction, the State University Railroad Company nearly went bankrupt and the whole mess was only barely saved by the intervention of the Richmond and Danville Railroad. In performing this bailout, the R&DRR entered into an agreement with the State University Railroad. The SURR was to complete the grading and the R&DRR would install the rails and provide the rolling stock. However, a misunderstanding arose between the two companies because each had expected the other to build the trestles over New Hope and Bolin Creeks. Ultimately the R&DRR went ahead and built the trestles, but consequently cut the budget somewhere else.

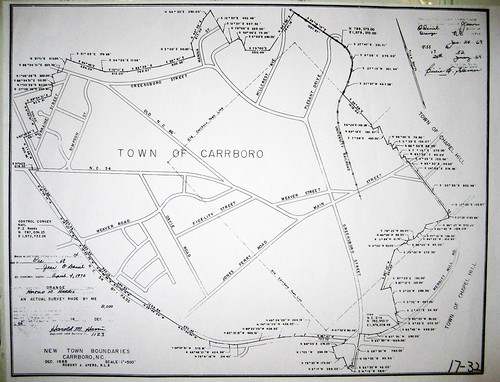

The written agreement is recorded in Hillsborough (ODB) and it explicitly states that the R&DRR was to complete the rail line "to the Town Line." But instead they stopped about 1/2 mile short of Merritt Mill Road where the town line was then and is now. So, realistically the most likely thing appears that the railhead is where it is because that was as close as they could get with the desperately strapped budget they had and everyone concluded that that was close enough. Also, the area that is now downtown Carrboro afforded a large flat area in which to build the wye.

The wye was the triangular rail configuration that allowed the engine to turn around. Two thirds of the wye still exists, the main line and the spur leading into the Fitch parking lot.

The Cotton and Hosiery Mills

12 [Slide of Lloyd Grist Mill]

Almost immediately after the railroad was complete, Thomas F. Lloyd built a steam powered gristmill and cotton gin next to the railhead in 1883. This building, which in recent years has been called the Broad Street Building, still stands near the northeast corner of the intersection of Main Street and the railroad tracks.

14 [Slide of Carr Mill]

In the northwest corner of the intersection Lloyd built a cotton and hosiery mill in 1898, creating an industry that Carrboro was built on.

That site is still the focal point of the community today.

Dr. John Florin co-authored an excellent narrative of the history of this phase of mill development as a preface to Carrboro, NC: An architectural and historical inventory, which I will not attempt to compete with.

After 10 years, Lloyd sold his Alberta Cotton Mill to Julian Shakespeare Carr. Carr also purchase another smaller mill that stood where Fitch lumber Co is today. Lloyd immediately set about building yet another mill (now gone) just south of the Alberta Mill. The textile industry was good to Carrboro for many years, but by the mid-1950’s Pacific Woolen Mills, the successors to Carr, closed shop for good.

During the golden age of mill development in Carrboro, many houses were built by the mill owners in order to supply their own workers with housing, much as was the case in mill villages across the South. And in this way, the old mill village of Carrboro grew largely the same way that many other company towns did. However by the time of the Depression business trends wandered away from the mill owner as residential landlord; the free market seemed to be a simpler way to address the mill worker housing problem. In 1939, the mills sold off most of Carrboro’s mill houses.

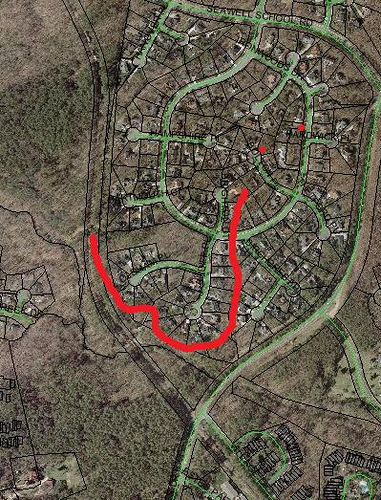

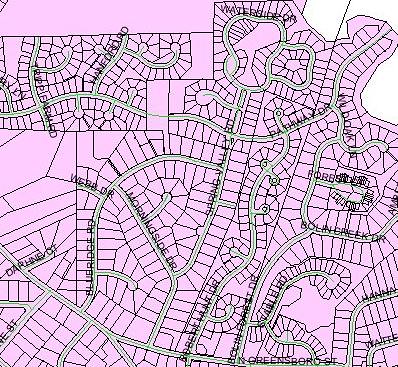

The relative flatness of downtown Carrboro was particularly helpful for laying out a rectilinear street grid initially:

But as with the old parts of Chapel Hill, as the street grid ran into topographic challenges, the grid was abandoned.

Also, later trends in city planning led away from street grids.

By 1969, the municipal boundaries of Carrboro encompassed about twice the area of the original municipal boundaries.

And then the Aldermen got a big idea.

They started approving large apartment complexes along the NC-54 Bypass in order to gain taxbase, mostly on the backs of UNC students who were no kind of political factor in Carrboro. However ultimately this theory backfired. As more and more students and recent graduates moved to Carrboro, they became a significant political force, especially with relation to the creation of Chapel Hill Transit, as well as the initiation of a policy requiring sidewalks in new developments, among numerous other environmental initiatives. Also, the 26th amendment lowered the voting age to 18 in 1972 and within a decade the students, hippies and recent graduates had taken over Carrboro town government.

This new school of Carrboro politics came along at the same time that a proposal surfaced to tear down the abandoned Pacific Woolen Mills, formerly Durham Hosiery Mill #5, the mill that Thomas Lloyd sold to Julian Shakespeare Carr, that place from which our community takes its name. A coalition of people came together including many new and old residents of Carrboro to oppose the demolition and eventually convinced a group of investors to step in and save the building, in part using a federal grant that came through the Town of Carrboro.

The combination of the political movement that initiated bus service in Carrboro and the local coalition that saved the historic mill building formed the foundation of modern politics in Carrboro – a paradigm that has its roots in the early 1970’s planning decisions made by the Board of Aldermen.

This was, of course, the furthest thing from the minds of the Carrboro born and bred men who made up the Board in the early 1970’s. I cannot help but wonder whether we are presently undergoing the same process, but in reverse. As more and more extremely expensive housing is built in suburban Carrboro, I wonder whether this will eventually change the character of our town.

Landscape and Memory

Having brought you more or less up to the present, it seems appropriate to move on to a discussion of the future of Carrboro, but before we go there, we need to discuss a curious aspect of life in Carrboro and Chapel Hill.

It has sometimes been said that everyone seems to think that Chapel Hill was perfect right about the time they got there. Along those lines, R. L. Gray in his 1904 essay on Chapel Hill wrote (from the News & Observer reprinted in NC Journal of Law, Vol 1, pp 516-518, 1904):

"Let the man have been tarred with the University stick and he will tell you along with his after-dinner cigar that he has a notion of some day building a house at Chapel Hill – and there remain to the end of the chapter in the one place where he believes he can obtain a large and perfect peace. There men cling to the town and its surroundings with a memory that is both tenacious and jealous of details.

"A friend was describing to one of these - a graduate before the [Civil] war – the site of the present Alumni Building. Suddenly the old graduate’s eyes flashed fire: “What!” he exclaimed. “You don’t tell me they’ve cut down the old college linden! I’d rather they’d have gone without that building forever than that they should have touched that tree!

"And so it goes. Living in the hearts of its scattered children, each tree shrub and rose bush, almost each stone of its serried ranks of rough built walls, bears its own faint story; and it is the indefinable suggestion that seems in time to float out from the inanimate things that have brushed on human hopes that strangely strikes the newcomer at the moment he places foot upon the campus and brings to the returned a tingling of the blood and a half forgotten smell of the air that at once exhilarate and recall to half sad dreams of bygone days."

Gray’s argument is essentially that the landscape of Chapel Hill is a part of the experience of being young and full of life in Chapel Hill. Revisiting the landscape of your young adulthood brings back fond memories of days gone by. Or in other words, there’s nothing like walking down Franklin Street to make you feel young again. And any change at UNC (or in Chapel Hill) detracts from that feeling.

Gray’s theory explains the experience of returning alumni, who for example are sometimes crestfallen to find that the Rathskeller is no more, or similarly are shocked to see Greenbridge rising on Chapel Hill’s western border. I am not sure that the experience is exactly the same for those who live in and near Chapel Hill and return to UNC and downtown on a regular basis, but it is at least part of that story.

Gray makes no remark on Carrboro in part because the village scarcely existed in 1904, but Carrboro is not immune to this same issue. Probably the greatest challenge facing our town is how our downtown can grow without compromising the sense of place that is Carrboro. And I suppose such things are challenges for any community, but I think Gray is suggesting that this phenomenon is especially strong in Chapel Hill because so many people discover the town as 18-year-olds, entering the prime of life and for the first time living with new found freedom. This is true for Carrboro as well, although somewhat less so because Carrboro is less a part of the undergraduate experience for most students.

As an aside, I love the detail that the fierce critic of change in Gray’s essay “has a notion of some day building a house at Chapel Hill.” Just one more house won’t hurt, as long as it is mine. From today’s vantage point, it also seems ironic that the critic would lament the construction of Alumni Hall:

Alumni Hall is one of the buildings that gives secondary definition to McCorkle Place and has many beautiful architectural details. That anti-Alumni Hall sentiment seems particularly ironic in light of Davie Hall, which UNC went on to build only 200 yards away:

The desire to return to a Chapel Hill that was known from earlier days goes still further back in UNC's history. William D. Moseley, a member of the UNC class of 1818, wrote a letter to his former professor Elisha Mitchell in 1853: “I know of no earthly pleasure which would afford me more heartfelt satisfaction than a short stay at that village [Chapel Hill]; where I could again refresh my memory with a review of the places and things that still remain as mementos of days that are past; when the future was looked to with hopes, never to be realized.”

And I must give credit where it is due, UNC has been creative in preserving some aspects of the historical landscape. Among Moseley’s other comments in his 1853 letter: “I would like too to visit the Old Poplar, in the right of the path leading from the Chapel to Dr Caldwell's. Is it still living?”

Not only was it still living in 1853, but it is still living today:

Moseley’s letter indicates that the Davie Poplar was a noted landmark even when the University was young. And clearly it was called “the Old Poplar” even by members of the class of 1818. It was already at least 100 years old when Moseley graduated. The Davie Poplar is now at least 300 years old and some think it may be approaching 400.

But nothing in this world lasts forever, and UNC began preparing for the inevitable about 90 years ago by grafting a cutting of the Davie Poplar to create Davie Poplar, Jr., which grows in the shadows of the original. And more recently a seedling of the Davie Poplar was cultivated and planted nearby with the appellation Davie Poplar, III. It's right in front of Alumni Hall as it happens. Maybe they could replant a college linden there? While obviously no one is hoping for the day when the Davie Poplar falls, it is reassuring to know that UNC has long since begun to prepare for that day.

Likewise, no one hopes for the day when our community will face dramatic changes brought about by greenhouse gasses as well as the ever-increasing cost (and ever-decreasing supply) of petroleum. But we cannot bury our heads in the sand and hope that such challenges will never come. At the local level, Carrboro, UNC and Chapel Hill can make only the most incremental changes to the composition of the atmosphere or the supply of available petroleum. But we can and we must prepare for the future that we know is coming.

Preparing for a world with fewer cars and less petroleum will partly involve technological breakthroughs in sustainable energy, but it must also involve dramatic improvements in energy efficiency. And one way for us to reduce our society’s demand for energy - a way that is entirely within the control of local government in North Carolina - is to change our built landscape – to create a more pedestrian, bicycle and transit friendly landscape. And that will involve a more compact form of development, focused on key transportation corridors.

One area that is appropriate for the new landscape that our community will need is the NC 54 corridor between Meadowmont and UNC, along the planned route of the Triangle’s light-rail system. Downtown Carrboro and downtown Chapel Hill are also areas where outstanding public transportation is already readily available and are appropriate places for more intense development. Yet, the importance of the landscape, the sense of place in these locations cannot be ignored.

How would Carrboro be Carrboro without these buildings:

On the other hand, some downtown Carrboro buildings seem considerably less essential:

To be clear these businesses are essential, but the buildings are not.

Likewise, the Best Western University Inn was a pretty unremarkable building. The grassy areas out front were pleasant, but it was mostly a low utilitarian building with a sea of asphalt in front. The picture above was taken as a publicity photo and it still makes the building and lot look unremarkable (at best). East54's critics only ever acknowledge this reality when prompted to do so. Likewise there seems to be no public acknowledgement that the site of Greenbridge was not long ago a flophouse for crack dealers. Does any of this mean that East54, Greenbridge or 300 E. Main Street will be perfect? Of course not. But let’s be clear, what they are replacing was not so terrific as some would like to pretend.

Change is inevitable for Carrboro and Chapel Hill. The challenge is to keep the elements that are central to our landscape from the past, while creating a more energy-efficient and pedestrian friendly landscape for the future. Personally, I think that is something that Carrboro, UNC and Chapel Hill can do.

Really good, Mark. Thanks for posting, and for putting so much work into it.

ReplyDeleteA great piece Mayor. Would have loved to have heard it in person.

ReplyDeleteMark K.

Thank you for the insight and the wonderful history lesson. Making my way through your older essays for the first time. Any new content going up in the future?

ReplyDeleteI am the 4th great granddaughter of Matthew McCauley and Martha Johnstone through their daughter Eleanore who married Wilson Atwater. I recently found your website while investigating the history of my McCauley family and I am thoroughly enjoying your information.

ReplyDelete