In the 1800's three African-Americans served on the Chapel Hill Town Council: Thomas Kirby and Green Brewer during Reconstruction, and Wilson Caldwell in the 1880's. These were what historian Eric Foner has called "Freedom's Lawmakers." I am reminded of the three of them by my post on the Congregationalist school that stood at the corner of Rosemary and Henderson Streets in Chapel Hill (see Freedman's School). I gave there a very brief sketch of one of the school's teachers, Wilson Caldwell. Now let me turn my attention to Thomas Kirby. I'll try to work up something on Green Brewer soon, but he is a more elusive figure.

Reliably, Kemp P. Battle tells us about a lot of 19th century figures in Chapel Hill and Thomas Kirby is no exception. Battle not only mentions Kirby in his History of the University of North Carolina, but also in his Sketch of the Life and Character of Wilson Caldwell. I also read W. J. Peele's A Pen-Picture of Wilson Caldwell, Colored, Late the Janitor of the University of North Carolina. Peele and Battle both give sterotypical views of Kirby (and Caldwell) which must be taken with a lot of salt ('slow shambling gate', 'burly yellow man') , but their comments are interesting nonetheless.

Battle tells us that Tom Kirby was "a big burly yellow man" and an "old issue free man of color" - that is, he was a free man from before the Civil War. Kirby was listed as "Mulatto" in the 1870 census. He worked for the University serving as an assistant janitor with and under Wilson Caldwell. Kirby served in the Old West building. In Battle's words, Kirby "never gained a high character for probity." Or in other words, he was viewed as being somewhat deceitful.

Both Battle and Peele relate parts of a tale about Kirby's purported lack of probity. Battle says: Kirby was "suspected in the days before the war of selling whiskey on the sly to students, a most lucrative business if detection did not follow, as the profits were from one hundred to a thousand per cent on the cost." Peele more graphically relates: "Pious-looking old Tom Kirby, the assistant janitor, was accused of bringing liquor to the students in his boot-legs - and they were indeed capacious enough to accommodate two or three pint ticklers each without impairing the gravity of his slow, shamblig gait." But Battle reassures us "Good behavior wiped out this suspicion, at least to the extent of making him eligible for employment by the University."

Battle also gives this curious account: "I witnessed, in truth I acted as judge, a ludicrous criminal trial of Kirby by a moot court, a trial conducted with all due colemnity, and as able as could be expected of neophytes in the law. Kirby was charged with mixing waters, that is of pouring fresh water from the well into buckets whos contents remained over from the night before. The fact was proved and then Frank Hines, a bright young man, soon afterwards drowned at Nag's Head, was brough in as a scientific expert, to prove that water kept for hours in a bedroom took in solution quantities of carbonic acid gas (carbon dioxide) and other deadly poistons. Of course Kirby was convicted by the jury but no punishment followed."

I found in the 1870 census, that Kirby's wife was Julia, born about 1825 in North Carolina; Kirby was ten years her senior, also born in NC. The 1870 census does not show any children, but Battle tells us that they had a son Edmund, "who was employed in the Chemical Laboratory. He was a preacher and some of his sermons are said to have contained most lurid metaphors, blazing with the transformations he had witnessed in the Laboratory." Battle also mentions that Thomas had a niece, Susan Kirby, who married Wilson Caldwell.

Regarding Green Brewer we know less, but he is listed in the 1880 census:

Green Brewer, Chapel Hill, Orange Co., North Carolina, Age: 48, born in North Carolina Wife: Cornelia, Occupation: Shoe Maker.

Saturday, March 28, 2009

The Freedman's School

In follow up to the essay below on the Preparatory School, let me say a little more that I have recently learned about the subsequent school for former slaves that stood a block to the south at the NE corner of Rosemary and Henderson Streets. Battle provides some more information about the matter in his Sketch of the Life of Wilson Caldwell (1895), but first let me explain (in case you don't know) who Wilson Caldwell was.

UNC Pres. Joseph Caldwell had a slave named November Caldwell who was highly regarded by the Chapel Hill community (as highly regarded as slaves could be said to have been). November's son Wilson was born a slave in 1841. Wilson's mother was a slave of David Swain, so he was given the name Wilson Swain at birth, but after emancipation Wilson went by Wilson Swain Cladwell. Wilson was also very highly thought of in Chapel Hill. He was appointed Justice of the Peace by Reconstruction Governor W. W. Holden. Wilson was also elected to the Chapel Hill Board of Commissioners in the 1880's (the third African American to serve on the Chapel Hill board). Wilson's descendants still live in this area and many of them have dedicated their lives to public service, particularly in the area of law enforcement.

So, here's the tie in with the school, Battle relates in his sketch: "This position [waiter at the University] he held until the beginning of 1869, when he resigned in disgust at the cutting down of his wages so low as not to be sufficient for a decent support in the style to which he had been accustomed . . . Caldwell, after throwing up his post in the University, applied for and obtained from Mr. Samuel Hughes, County Superintendent of Public Schools, a license to take charge of a free school for colored children in Chapel Hill at $17.50 per month . . . In his church relations, he differs from the most of his race at Chapel Hill. He is a memebr of the Congregational Church, which for several years has been supporting a school for the colored in the old Methodist church, bought when the Methodists moved into their larger more beautfiul building on Franklin (or main) street."

So it appears that Wilson Caldwell was the teacher/principal of the school house at the corner of Henderson and Rosemary. And based on the timing, it sounds as though he may have been the first teacher/principal of that school.

Also it seems clear that Wilson Caldwell's school was in the exact same building that had been the Methodist Church. The website of University UMC Church states: "In 1850, Samuel Milton Frost, a university student, served as minister. Determined to carry out Deems’ plan to build a church, Frost traveled the state and raised $5,000 for a church building. The church — dedicated in 1853 — still stands on Rosemary Street."

Battle's History also relates: "he joined the Congregational Church. This denomination did not flourish in Chapel Hill. Soon after Caldwell's death [in 1898] its authorities sold their church building and schoolhouse and left the village."

So here is the approximate chronology of the corner of Henderson and Rosemary Streets:

1853 Methodists build church

1868 Methodists buy new lot on Franklin Street

1869 Congregationalists open school for African Americans

1898 Congregationalists sell school building

UNC Pres. Joseph Caldwell had a slave named November Caldwell who was highly regarded by the Chapel Hill community (as highly regarded as slaves could be said to have been). November's son Wilson was born a slave in 1841. Wilson's mother was a slave of David Swain, so he was given the name Wilson Swain at birth, but after emancipation Wilson went by Wilson Swain Cladwell. Wilson was also very highly thought of in Chapel Hill. He was appointed Justice of the Peace by Reconstruction Governor W. W. Holden. Wilson was also elected to the Chapel Hill Board of Commissioners in the 1880's (the third African American to serve on the Chapel Hill board). Wilson's descendants still live in this area and many of them have dedicated their lives to public service, particularly in the area of law enforcement.

So, here's the tie in with the school, Battle relates in his sketch: "This position [waiter at the University] he held until the beginning of 1869, when he resigned in disgust at the cutting down of his wages so low as not to be sufficient for a decent support in the style to which he had been accustomed . . . Caldwell, after throwing up his post in the University, applied for and obtained from Mr. Samuel Hughes, County Superintendent of Public Schools, a license to take charge of a free school for colored children in Chapel Hill at $17.50 per month . . . In his church relations, he differs from the most of his race at Chapel Hill. He is a memebr of the Congregational Church, which for several years has been supporting a school for the colored in the old Methodist church, bought when the Methodists moved into their larger more beautfiul building on Franklin (or main) street."

So it appears that Wilson Caldwell was the teacher/principal of the school house at the corner of Henderson and Rosemary. And based on the timing, it sounds as though he may have been the first teacher/principal of that school.

Also it seems clear that Wilson Caldwell's school was in the exact same building that had been the Methodist Church. The website of University UMC Church states: "In 1850, Samuel Milton Frost, a university student, served as minister. Determined to carry out Deems’ plan to build a church, Frost traveled the state and raised $5,000 for a church building. The church — dedicated in 1853 — still stands on Rosemary Street."

Battle's History also relates: "he joined the Congregational Church. This denomination did not flourish in Chapel Hill. Soon after Caldwell's death [in 1898] its authorities sold their church building and schoolhouse and left the village."

So here is the approximate chronology of the corner of Henderson and Rosemary Streets:

1853 Methodists build church

1868 Methodists buy new lot on Franklin Street

1869 Congregationalists open school for African Americans

1898 Congregationalists sell school building

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

The Perparatory School

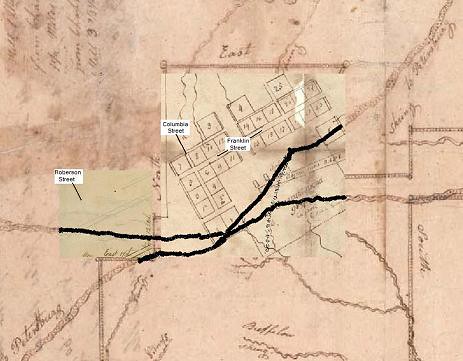

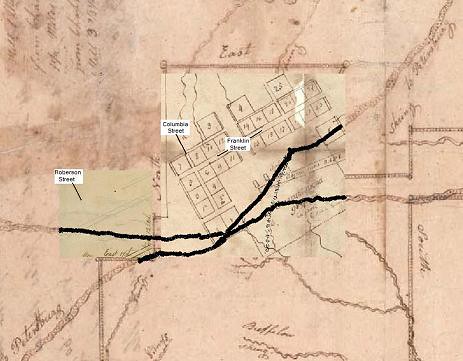

Recently I took note of an interesting detail on the 1817 Plan of Chapel Hill. At the north end of town the map shows the Preparatory School:

As you can see by comparing the modern tax map (on which I have drawn the original lots in red), the Preparatory School was originally at the site that is now the NE corner of Henderson and Rosemary Streets.

Battle's History relates a lot of detail about the Grammar or Preparatory School. A few highlights follow: "In December, 1795 . . . the Board determined to erect a house for a Grammar School . . . a place peculiarly lonely, but near two never-failing springs of purest water."

Presumably Battle means the two springs shown on the 1817 Plan of Chapel Hill. These are not very discernible today, but must be in the vicinity of the old Post Office and somewhat east of there. These springs are the headwaters of Foxhall Branch, a tributary of Bolin Creek.

Battle continues "When Abner W. Clopton gave up the Grammar School in 1819, the University abandoned it . . left to the bats and owls" and under financial pressure in 1831, the University sold "the Preparatory School Acre . . . after some years in the occupancy of a . . . professional hunter . . . Peyton Clements."

A nearby lot has long been said to have been the site of a Freedmen's School, that is, a school for the education of freed slaves after the Civil War. Joe Herzenberg (who lived a block away) often told me so.

Battle mentions later: "Another portion of Grand Avenue was bought by the Methodists as a site for their church, and, when they concluded to build another, some northern Congregationalists bought it for a school and church for the colored. It has since been sold into private hands." By Grand Avenue, Battle means the broad avenue that was once planned to run between lots 11 & 13 and between lots 12 & 14, so it appears that Battle is describing the corner of Rosemary and Henderson Streets.

As you can see by comparing the modern tax map (on which I have drawn the original lots in red), the Preparatory School was originally at the site that is now the NE corner of Henderson and Rosemary Streets.

Battle's History relates a lot of detail about the Grammar or Preparatory School. A few highlights follow: "In December, 1795 . . . the Board determined to erect a house for a Grammar School . . . a place peculiarly lonely, but near two never-failing springs of purest water."

Presumably Battle means the two springs shown on the 1817 Plan of Chapel Hill. These are not very discernible today, but must be in the vicinity of the old Post Office and somewhat east of there. These springs are the headwaters of Foxhall Branch, a tributary of Bolin Creek.

Battle continues "When Abner W. Clopton gave up the Grammar School in 1819, the University abandoned it . . left to the bats and owls" and under financial pressure in 1831, the University sold "the Preparatory School Acre . . . after some years in the occupancy of a . . . professional hunter . . . Peyton Clements."

A nearby lot has long been said to have been the site of a Freedmen's School, that is, a school for the education of freed slaves after the Civil War. Joe Herzenberg (who lived a block away) often told me so.

Battle mentions later: "Another portion of Grand Avenue was bought by the Methodists as a site for their church, and, when they concluded to build another, some northern Congregationalists bought it for a school and church for the colored. It has since been sold into private hands." By Grand Avenue, Battle means the broad avenue that was once planned to run between lots 11 & 13 and between lots 12 & 14, so it appears that Battle is describing the corner of Rosemary and Henderson Streets.

Sunday, March 22, 2009

Leroy Couch of Couchtown

In Battle's History of UNC, on page 607, Kemp P. Battle relates the tale of Leroy Couch and the long forgotten community of Couchtown: "The name of a singular character should be recorded - Leroy Couch, a white man. He once owned, it is said, considerable substance, but lost it by dissipation. He seems to have no kin. He sought no acquaintances. He bought or squatted on an acre near the eastern edge of the town and with the remnants of his possessions lived a hard, squalid and solitary life."

In the 1850 census Lee Couch is listed with wife Sally and children William (15), Louisa (12), and Jonathan (9). But by the 1860 census he was listed as living alone, so something must have happened to his family. Both census entries list him as owning real estate.

Battle continues: "In some way it was discovered that he was a faithful and skillful nurse and, on petition of nearly the entire student body, he was employed for years in all cases of severe sickness among the students."

Perhaps Mr. Couch's family died of disease and he gained experience as a nurse through their suffering. Battle's statments about the student petition are confirmed by a petition contained in University Papers #40005 from 1853 or 1854, which recognizes Lee Couch, who "has devoted himself entirely to [the students'] service." The petition continues: "The College servants for some year or two past have been-as they say-unable to perform the various duties assigned to them."

Battle's History continues: "Without pretending to independent knowledge, he implicitly obeyed the doctors, watched his patients with unsleeping vigilance and rendered the needful service with regularity. When the University was closed [2/1/1871], as if his mission was finished, he returned to his solitary life, was extremely poor, but never begged and, when decrepit, died in the county home for paupers."

Here again, independent records support Battle. The County Home death records include this item:

Lee (Leroy) Couch

Born: c. 1800 [the 1870 census gives his YOB as 1802]

Died: June 25, 1876

Race: White

Battle further relates: "Two or three other houses were built near his, and the settlement, seperate from the village habitations, was called Couchtown. Handsome residences extend to this distant and obscure hamlet." In his prior book Sketches of the History of UNC, Battle also mentions that in the 1850's the University grew so much that students "overflowed the old buildings and were camped in little cottages all over the town from Couchtown to Craig's." In response, New East and New West were completed in 1859 to accomodate the expanded student body. Battle also mentions Couchtown in Volume II of his History on page 92: "When [Francis and Robert Winston's] reached the boundary line of Chapel Hill at the hamlet of Couchtown, the hilltop on the Durham road, the elder suddenly leaped from the vehicle and dashed forward with the amazing speed for which duck-legged youths are often famous, shouting, 'Hurrah! I am the first student on the Hill!'" This was at the reopening of the University in 1875.

In all, it would appear that Couchtown was somewhere "near the eastern edge of the town" [Boundary Street], at "the hilltop on the Durham road" [Franklin Street] at a place to which "handsome residences" extended in 1907. I assume that this was in the vicinity of Davie Circle.

In the 1850 census Lee Couch is listed with wife Sally and children William (15), Louisa (12), and Jonathan (9). But by the 1860 census he was listed as living alone, so something must have happened to his family. Both census entries list him as owning real estate.

Battle continues: "In some way it was discovered that he was a faithful and skillful nurse and, on petition of nearly the entire student body, he was employed for years in all cases of severe sickness among the students."

Perhaps Mr. Couch's family died of disease and he gained experience as a nurse through their suffering. Battle's statments about the student petition are confirmed by a petition contained in University Papers #40005 from 1853 or 1854, which recognizes Lee Couch, who "has devoted himself entirely to [the students'] service." The petition continues: "The College servants for some year or two past have been-as they say-unable to perform the various duties assigned to them."

Battle's History continues: "Without pretending to independent knowledge, he implicitly obeyed the doctors, watched his patients with unsleeping vigilance and rendered the needful service with regularity. When the University was closed [2/1/1871], as if his mission was finished, he returned to his solitary life, was extremely poor, but never begged and, when decrepit, died in the county home for paupers."

Here again, independent records support Battle. The County Home death records include this item:

Lee (Leroy) Couch

Born: c. 1800 [the 1870 census gives his YOB as 1802]

Died: June 25, 1876

Race: White

Battle further relates: "Two or three other houses were built near his, and the settlement, seperate from the village habitations, was called Couchtown. Handsome residences extend to this distant and obscure hamlet." In his prior book Sketches of the History of UNC, Battle also mentions that in the 1850's the University grew so much that students "overflowed the old buildings and were camped in little cottages all over the town from Couchtown to Craig's." In response, New East and New West were completed in 1859 to accomodate the expanded student body. Battle also mentions Couchtown in Volume II of his History on page 92: "When [Francis and Robert Winston's] reached the boundary line of Chapel Hill at the hamlet of Couchtown, the hilltop on the Durham road, the elder suddenly leaped from the vehicle and dashed forward with the amazing speed for which duck-legged youths are often famous, shouting, 'Hurrah! I am the first student on the Hill!'" This was at the reopening of the University in 1875.

In all, it would appear that Couchtown was somewhere "near the eastern edge of the town" [Boundary Street], at "the hilltop on the Durham road" [Franklin Street] at a place to which "handsome residences" extended in 1907. I assume that this was in the vicinity of Davie Circle.

The Original Intersection

Today, the 100% corner in Chapel Hill is the intersection of Franklin Street and Columbia Street - the very heart of the town. But orginally, the center of development was a couple blocks south of there. Let's take a closer look.

Chapel Hill, as you probably already know, was developed by European settlers as a "chapel of ease" on top of a hill. The New Hope Chapel was about where the Carolina Inn stands now. The New Hope Chapel was located at the intersection of two early roads. One road went from Pittsboro to Oxford (essentially what is now US Highway 15) and the other road came west from Raleigh and headed into what is now Carrboro connecting to modern day Old Fayetteville Road/Old NC 86.

The original route of the Pittsboro-Oxford road went through the middle of the UNC campus, travelling right between South Building and Old East. From there it wandered north of Cameron Avenue turning into, approximately, Hooper Lane then Park Place and then following Franklin Street's great curving route down Strowd Hill. To the west, this same road wandered a bit south of West Cameron Ave. and then ran right along Cameron a short ways, bending south along what is now Merritt Mill Road and probably following Smith Level Road out of Orange County.

To piece together what that route looked like, I scaled and superimposed several different maps of the area, including the 1852 Grandy map, the 1792 Daniel map and the 1795 Plan of the Situation of the University. Here's the result:

The other road was essentially modern-day Raleigh Road approaching from the east and wandering at an odd angle to Franklin Street etc., more or less becoming Main Street/Weaver Street, N. Greensboro Street in Carrboro.

Chapel Hill, as you probably already know, was developed by European settlers as a "chapel of ease" on top of a hill. The New Hope Chapel was about where the Carolina Inn stands now. The New Hope Chapel was located at the intersection of two early roads. One road went from Pittsboro to Oxford (essentially what is now US Highway 15) and the other road came west from Raleigh and headed into what is now Carrboro connecting to modern day Old Fayetteville Road/Old NC 86.

The original route of the Pittsboro-Oxford road went through the middle of the UNC campus, travelling right between South Building and Old East. From there it wandered north of Cameron Avenue turning into, approximately, Hooper Lane then Park Place and then following Franklin Street's great curving route down Strowd Hill. To the west, this same road wandered a bit south of West Cameron Ave. and then ran right along Cameron a short ways, bending south along what is now Merritt Mill Road and probably following Smith Level Road out of Orange County.

To piece together what that route looked like, I scaled and superimposed several different maps of the area, including the 1852 Grandy map, the 1792 Daniel map and the 1795 Plan of the Situation of the University. Here's the result:

The other road was essentially modern-day Raleigh Road approaching from the east and wandering at an odd angle to Franklin Street etc., more or less becoming Main Street/Weaver Street, N. Greensboro Street in Carrboro.

Friday, March 20, 2009

Abolitionism at UNC?

I came across a couple of interesting quotes in William Hooper's An Oration Delivered at Chapel Hill on Wednesday, June 24, 1829 (Hillsborough: D. Heartt, 1829). This was the grandson of William Hooper, the signer of the Declaration of Independence. The grandson was a professor at UNC and gave this address to the students on the eve of graduation in 1829.

“Let every American believe, let every child be brought up to think, that as soon as the chain of our union is broken, this continent, hitherto so peaceful and harmonious, will become, what Europe has so long been, the bloody arena of perpetual strife between neighboring nations . . .”

“That slavery is the baneful parent of the vilest morals, every virtuous family in this southern country knows full well, and deplores that it holds within its own walls a fountain of moral poison, which, in spite of the most watchful care, is continually diffusing around its baleful influence and infecting the health of all the household; while public testimony to the same mournful fact is furnished by every jail and gibbet in the land. Many of the state governments have awaked to the importance of this subject, and we may hope that the progress of political wisdom and an increasing sense of the magnitude of the evil, will enlist the remainder, who now stand back in indifference or despair, until at length a unanimity shall be effected, by which the collective wisdom and resources of the nation shall be put into action for the extirpation of the bitter root from our soil.”

I wonder what sort of stir these comments caused on campus!

“Let every American believe, let every child be brought up to think, that as soon as the chain of our union is broken, this continent, hitherto so peaceful and harmonious, will become, what Europe has so long been, the bloody arena of perpetual strife between neighboring nations . . .”

“That slavery is the baneful parent of the vilest morals, every virtuous family in this southern country knows full well, and deplores that it holds within its own walls a fountain of moral poison, which, in spite of the most watchful care, is continually diffusing around its baleful influence and infecting the health of all the household; while public testimony to the same mournful fact is furnished by every jail and gibbet in the land. Many of the state governments have awaked to the importance of this subject, and we may hope that the progress of political wisdom and an increasing sense of the magnitude of the evil, will enlist the remainder, who now stand back in indifference or despair, until at length a unanimity shall be effected, by which the collective wisdom and resources of the nation shall be put into action for the extirpation of the bitter root from our soil.”

I wonder what sort of stir these comments caused on campus!

Thursday, March 12, 2009

Dimmocks Mill

Well . . . wrong again. So I looked up Thomas D. Crain deeds to see whether the mill that he advertsied in the Hillsborough Recorder (see The Life and Times of Buck Taylor posted earlier this month) was on Bolin Creek, but it wasn't. First, it was not Buck taylor at all. It was his son John Taylor jr. Second, it appears to have been on the Eno River. The mill was best known as Dimmocks Mill and was located near the confluence of Seven Mile Creek and the Eno River (where Dimmocks Mill Road crosses the river today).

I figured that as long as I am at it, I might as well run out the title history on Dimmocks Mill, so here's what I found:

John Thompson to John Taylor jr. (1817 & 1820) Orange Deed Book (ODB) 21, pages 506&507

John Taylor jr to Thomas D. Crain & Alfred Moore (12/9/1823) ODB 21, page 508

Thomas D. Crain to Dr. J S Smith ODB 28, page 436

Francis J Smith to W H Brown (11/25/1847) ODB 34, page 122

Brown to Dickson & Parks - did not find connecting deeds

Thomas Dickson & David C Parks to Edwin Dimmock, Thomas B Thompson & Samuel K Scott (4/29/1875) ODB 43, page 294

I stopped here because I think the Dimmock family was the last owner before the mill closed. Plus I ran out of time.

Incientally, John Taylor jr. only bought part of the property in the two transactions with John Thompson, but one of the deeds mentions that the transaction is being entered into because John Taylor jr. wants to build a grist and saw mill. So there apparently was no mill prior to that time.

I figured that as long as I am at it, I might as well run out the title history on Dimmocks Mill, so here's what I found:

John Thompson to John Taylor jr. (1817 & 1820) Orange Deed Book (ODB) 21, pages 506&507

John Taylor jr to Thomas D. Crain & Alfred Moore (12/9/1823) ODB 21, page 508

Thomas D. Crain to Dr. J S Smith ODB 28, page 436

Francis J Smith to W H Brown (11/25/1847) ODB 34, page 122

Brown to Dickson & Parks - did not find connecting deeds

Thomas Dickson & David C Parks to Edwin Dimmock, Thomas B Thompson & Samuel K Scott (4/29/1875) ODB 43, page 294

I stopped here because I think the Dimmock family was the last owner before the mill closed. Plus I ran out of time.

Incientally, John Taylor jr. only bought part of the property in the two transactions with John Thompson, but one of the deeds mentions that the transaction is being entered into because John Taylor jr. wants to build a grist and saw mill. So there apparently was no mill prior to that time.

Wednesday, March 11, 2009

Old Cape Fear River Charts

I admit this goes outside the Piedmont, but lately I have been looking at old governmental charts of the Cape Fear River. Many of these can be found on the NC Maps website:

http://www.lib.unc.edu/dc/ncmaps/browse_location.html

But some have not found their way onto that site (yet). Here's an effort at a checklist of charts of the Cape Fear River (bold indicates that it is NOT on the NC Maps site):

The James Glynn Maps:

Cape Fear River, [1839].

A Chart of the Entrance of Cape Fear River, 1839. UNC has a paper copy.

Continuation of the survey of Cape Fear River, [1839].

United States Coast Survey:

D-6 Sketch showing the progress of the survey at Cape Fear River & Frying Pan Shoals, 1851. From 1851 Report of USCS.

D-7 Sketch of Frying Pan Shoals and Cape Fear River, 1851. From 1851 Report of USCS.

D-2 Progress of Survey of Cape Fear and Vicinity to New River, 1852. From 1852 Report of USCS. Retitled "Sketch of Progress of Survey of Cape Fear and Vicinity to South Carolina" in 1853 Report of USCS.

D-? Preliminary chart of the entrances to Cape Fear River and New Inlet, 1853. I think this was included in the 1853 Report of USCS. UNC has a paper copy.

Preliminary sketch of the entrances to Cape Fear River and New Inlet, 1853.

Chart of Bar Cape Fear River, 1853.

Chart of New Inlet Cape Fear River, 1853.

#16 or D-3 Preliminary chart of lower part of Cape Fear River, 1855. From 1855 Report of USCS. Also 1856 edition in the 1856 Report of USCS. Later became #424 below.

#32 Preliminary chart of Frying Pan Shoals and entrances to Cape Fear River, 1857. UNC has a paper copy of this.

Comparative chart of Cape Fear River entrances, 1857. UNC has a paper copy.

Cape Fear River, 1858?-1865?

Comparative chart of Cape Fear River Bars, 1858. From 1858 USCS Report. UNC does not have this.

#12 Comparative chart of New Inlet Bar, northern entrance of Cape Fear River, 1858? UNC has a paper copy.

#48 Cape Fear and approaches, including the river to Wilmington, 1863. Also undated.

Army Corps of Topographical Engineers:

Chart of New Inlet, Cape Fear River, 1853?

Chart of Bar, Cape Fear River, 1853?

Both of these are in Message from the President of the United States to Congress, 1853.

US Coast and Geodetic Survey:

#149 Old Topsail Inlet to Cape Fear, 1889. Also 1897.

#150 Masonboro Inlet to Shallotte Inlet, including Cape Fear, 1888. Also 1897.

#424 Cape Fear River, from entrance to Reeves Point, 1866. Also 1887, 1888, & 1897. Included in 1865 Report of USCS under title "Entrances to Cape Fear River."

#425 Cape Fear River, from Reeves Point to Wilmington, 1888. Also 1893, 1897 & 1899. AKA "Federal Point to Wilmington."

Army Corps of Engineers:

1. Present Progress Cape Fear River (below Wilmington), 1884-1885. From the 1885 Report.

2. Fayetteville Shoals and McCarter's Cross, 1885. From the 1885 Report.

The 1886 Report has a fold-out map that I have not seen.

3. Wilmington . . . Snow's Marsh Channel, 1888. The 1888 Report contains a fold-out map, but I am not sure what the title is - something along the above lines.

4. Cape Fear River, NC Above Wilmington - Shoals and Jetties Sheet 1, 1889. There were apparently three sheets with this title and I suppose they came from the 1890 Report. I have only seen sheets 2 and 3.

5. Cape Fear River, NC Above Wilmington - Shoals and Jetties Sheet 2, 1889. Covers McCarter's Cross Shoal, Old Jetties Shoal, Evans Narrows Shoal, Smith's Cross Shoal, Rockfish Creek Shoal.

6. Cape Fear River, NC Above Wilmington - Shoals and Jetties Sheet 3, 1889. Covers Thames Shoal, The Dodge Shoals and Windom's Shoal.

7. Improvement of Cape Fear River, N.C. above Wilmington - McCarter's Cross Shoals and Cypress Shoals, 1896.

8. ? There were at least two other pertinent fold-outs in the 1896 Report of the Chief of Engineers, but I have not seen them.

9. ?

Apparently maps were produced in 1895 for possible improvments above Fayetteville, but they were not included in the 1896 Report; however the maps were included in House Document 65 from the 54th session. No copy of that House Document has been located.

The 1872 Report includes more information on possible improvements above Fayetteville on pages 741-749. The 1873 Report has a lengthy discussion of the river below Wilmington and old charts that were then available, but none of the charts were reproduced for the report.

There were several other charts of the work of the ACE and I am gradually assembling a list of those.

http://www.lib.unc.edu/dc/ncmaps/browse_location.html

But some have not found their way onto that site (yet). Here's an effort at a checklist of charts of the Cape Fear River (bold indicates that it is NOT on the NC Maps site):

The James Glynn Maps:

Cape Fear River, [1839].

A Chart of the Entrance of Cape Fear River, 1839. UNC has a paper copy.

Continuation of the survey of Cape Fear River, [1839].

United States Coast Survey:

D-6 Sketch showing the progress of the survey at Cape Fear River & Frying Pan Shoals, 1851. From 1851 Report of USCS.

D-7 Sketch of Frying Pan Shoals and Cape Fear River, 1851. From 1851 Report of USCS.

D-2 Progress of Survey of Cape Fear and Vicinity to New River, 1852. From 1852 Report of USCS. Retitled "Sketch of Progress of Survey of Cape Fear and Vicinity to South Carolina" in 1853 Report of USCS.

D-? Preliminary chart of the entrances to Cape Fear River and New Inlet, 1853. I think this was included in the 1853 Report of USCS. UNC has a paper copy.

Preliminary sketch of the entrances to Cape Fear River and New Inlet, 1853.

Chart of Bar Cape Fear River, 1853.

Chart of New Inlet Cape Fear River, 1853.

#16 or D-3 Preliminary chart of lower part of Cape Fear River, 1855. From 1855 Report of USCS. Also 1856 edition in the 1856 Report of USCS. Later became #424 below.

#32 Preliminary chart of Frying Pan Shoals and entrances to Cape Fear River, 1857. UNC has a paper copy of this.

Comparative chart of Cape Fear River entrances, 1857. UNC has a paper copy.

Cape Fear River, 1858?-1865?

Comparative chart of Cape Fear River Bars, 1858. From 1858 USCS Report. UNC does not have this.

#12 Comparative chart of New Inlet Bar, northern entrance of Cape Fear River, 1858? UNC has a paper copy.

#48 Cape Fear and approaches, including the river to Wilmington, 1863. Also undated.

Army Corps of Topographical Engineers:

Chart of New Inlet, Cape Fear River, 1853?

Chart of Bar, Cape Fear River, 1853?

Both of these are in Message from the President of the United States to Congress, 1853.

US Coast and Geodetic Survey:

#149 Old Topsail Inlet to Cape Fear, 1889. Also 1897.

#150 Masonboro Inlet to Shallotte Inlet, including Cape Fear, 1888. Also 1897.

#424 Cape Fear River, from entrance to Reeves Point, 1866. Also 1887, 1888, & 1897. Included in 1865 Report of USCS under title "Entrances to Cape Fear River."

#425 Cape Fear River, from Reeves Point to Wilmington, 1888. Also 1893, 1897 & 1899. AKA "Federal Point to Wilmington."

Army Corps of Engineers:

1. Present Progress Cape Fear River (below Wilmington), 1884-1885. From the 1885 Report.

2. Fayetteville Shoals and McCarter's Cross, 1885. From the 1885 Report.

The 1886 Report has a fold-out map that I have not seen.

3. Wilmington . . . Snow's Marsh Channel, 1888. The 1888 Report contains a fold-out map, but I am not sure what the title is - something along the above lines.

4. Cape Fear River, NC Above Wilmington - Shoals and Jetties Sheet 1, 1889. There were apparently three sheets with this title and I suppose they came from the 1890 Report. I have only seen sheets 2 and 3.

5. Cape Fear River, NC Above Wilmington - Shoals and Jetties Sheet 2, 1889. Covers McCarter's Cross Shoal, Old Jetties Shoal, Evans Narrows Shoal, Smith's Cross Shoal, Rockfish Creek Shoal.

6. Cape Fear River, NC Above Wilmington - Shoals and Jetties Sheet 3, 1889. Covers Thames Shoal, The Dodge Shoals and Windom's Shoal.

7. Improvement of Cape Fear River, N.C. above Wilmington - McCarter's Cross Shoals and Cypress Shoals, 1896.

8. ? There were at least two other pertinent fold-outs in the 1896 Report of the Chief of Engineers, but I have not seen them.

9. ?

Apparently maps were produced in 1895 for possible improvments above Fayetteville, but they were not included in the 1896 Report; however the maps were included in House Document 65 from the 54th session. No copy of that House Document has been located.

The 1872 Report includes more information on possible improvements above Fayetteville on pages 741-749. The 1873 Report has a lengthy discussion of the river below Wilmington and old charts that were then available, but none of the charts were reproduced for the report.

There were several other charts of the work of the ACE and I am gradually assembling a list of those.

Wednesday, March 4, 2009

The Life and Times of Buck Taylor

John "Buck" Taylor was a Chapel Hill character from the early days. After serving in the Continental Army during the Revolution, Taylor was hired as the first Steward of the University of North Carolina. As Battle's History relates: "In addition to furnishing food, the Board required the steward to give the floors, passages and staircases a fortnightly washing, to have the students' rooms swept and beds made once a day, and to have brought from ‘the spring' at least four times a day a sufficient quantity of water."

Evidently Taylor's meals were not popular with the students and after three years of service, Taylor quit. Not long after, Taylor began the operation of tavern on Franklin Street in Chapel Hill. The tavern stood more or less where Graham Memorial Hall is today and was in operation up into the 1820's. Later in life, Taylor served as the Clerk of Court for Orange County. Taylor also had a brief stint as Superintendant of Buildings and Grounds at UNC.

It has long been reputed that Taylor was overly fond of whiskey, so much so that local legend tells us that Taylor was buried standing upright - with a whiskey jug in each hand! While I doubt that he was buried upright, claims about Taylor's dipsomania are apparently substantiated by an entry I found in the minutes of the November 1799 Orange County Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions:

"John Taylor Esquire appearing in open Court intoxicated with liquor and having shewn and committed great contempt to the authority of this court sitting in its judicial capacity . . .It is commanded by the said Court that the said John Taylor be fined in the sum of ten pounds and that he be committed to close custody in the Gaol of this County until the end of this present term (about a week) without bail . . ."

Mind you, this happened while Taylor was serving as the Clerk of Court!

The tale of Taylor's upright burial has an alternate (but similarly apocraphyl) explanation, as Battle's History relates: "When he came to his death-bed he requested to be buried on the summit of a woody hill overlooking cultivated fields, so that he could watch the negroes and keep them at their work." I haven't found anything which demonstrates how Taylor treated his slaves, but there is certainly plenty of evidence in the Orange County deed books and the Hillsborough Recorder that Taylor owned several slaves.

At some point, Taylor apparently bought a farm in the vicinity of what is now the Cates Farm and Cobblestone neighborhoods in Carrboro. His name is memorialized by the street named Buck Taylor Trail in Cates Farm, and his much-discussed grave is in the yard of one of the houses on Buck Taylor Trail. Battle relates that "The monument is a sandstone slab, and on it. 'To the Memory of John Taylor. Born June 22, 1747; died May 28, 1828. A Patriot of 1776.'"

It has long been said around this area that Taylor was also the owner of the now-ruined gristmill on Bolin Creek. While no deeds have yet been found that would prove whether John "Buck" Taylor owned that mill, I just yesterday stumbled across an ad in the Nov 19, 1828 Hillsborough Recorder: "PUBLIC SALE. THOMAS D CRANE will offer for sale, on accomodating terms, on the second day of next County Court, being the 25th instant, all his interest in the mill formerly owned by John Taylor, Esq."

UPDATE:

Well . . . wrong again. So I looked up Thomas D. Crain deeds in Hillsborough and it turns out that the mill he owned (formerly the property of John Taylor Esq) was on the Eno River. The mill was best known as Dimmocks Mill and was located near the confluence of Seven Mile Creek and the Eno River (where Dimmocks Mill Road crosses the river today). So apparently Buck Taylor owned Dimmocks Mill; that does not rule out the possibility that Taylor also owned Castleberry site. But we are just back to rumor and conjecture on that. Orange Deed Book 28, pg 436 Thomas D Crain to Dr. J S Smith conveying three parcels including Dimmocks Mill.

Evidently Taylor's meals were not popular with the students and after three years of service, Taylor quit. Not long after, Taylor began the operation of tavern on Franklin Street in Chapel Hill. The tavern stood more or less where Graham Memorial Hall is today and was in operation up into the 1820's. Later in life, Taylor served as the Clerk of Court for Orange County. Taylor also had a brief stint as Superintendant of Buildings and Grounds at UNC.

It has long been reputed that Taylor was overly fond of whiskey, so much so that local legend tells us that Taylor was buried standing upright - with a whiskey jug in each hand! While I doubt that he was buried upright, claims about Taylor's dipsomania are apparently substantiated by an entry I found in the minutes of the November 1799 Orange County Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions:

"John Taylor Esquire appearing in open Court intoxicated with liquor and having shewn and committed great contempt to the authority of this court sitting in its judicial capacity . . .It is commanded by the said Court that the said John Taylor be fined in the sum of ten pounds and that he be committed to close custody in the Gaol of this County until the end of this present term (about a week) without bail . . ."

Mind you, this happened while Taylor was serving as the Clerk of Court!

The tale of Taylor's upright burial has an alternate (but similarly apocraphyl) explanation, as Battle's History relates: "When he came to his death-bed he requested to be buried on the summit of a woody hill overlooking cultivated fields, so that he could watch the negroes and keep them at their work." I haven't found anything which demonstrates how Taylor treated his slaves, but there is certainly plenty of evidence in the Orange County deed books and the Hillsborough Recorder that Taylor owned several slaves.

At some point, Taylor apparently bought a farm in the vicinity of what is now the Cates Farm and Cobblestone neighborhoods in Carrboro. His name is memorialized by the street named Buck Taylor Trail in Cates Farm, and his much-discussed grave is in the yard of one of the houses on Buck Taylor Trail. Battle relates that "The monument is a sandstone slab, and on it. 'To the Memory of John Taylor. Born June 22, 1747; died May 28, 1828. A Patriot of 1776.'"

It has long been said around this area that Taylor was also the owner of the now-ruined gristmill on Bolin Creek. While no deeds have yet been found that would prove whether John "Buck" Taylor owned that mill, I just yesterday stumbled across an ad in the Nov 19, 1828 Hillsborough Recorder: "PUBLIC SALE. THOMAS D CRANE will offer for sale, on accomodating terms, on the second day of next County Court, being the 25th instant, all his interest in the mill formerly owned by John Taylor, Esq."

UPDATE:

Well . . . wrong again. So I looked up Thomas D. Crain deeds in Hillsborough and it turns out that the mill he owned (formerly the property of John Taylor Esq) was on the Eno River. The mill was best known as Dimmocks Mill and was located near the confluence of Seven Mile Creek and the Eno River (where Dimmocks Mill Road crosses the river today). So apparently Buck Taylor owned Dimmocks Mill; that does not rule out the possibility that Taylor also owned Castleberry site. But we are just back to rumor and conjecture on that. Orange Deed Book 28, pg 436 Thomas D Crain to Dr. J S Smith conveying three parcels including Dimmocks Mill.

Sunday, March 1, 2009

The Robber's Den

UNC Pres. Kemp Plummer Battle relates the following in the History of the University of North Carolina (which this blog will hereafter just call Battle's History because I intend to blog about it quite a bit more):

"About a mile toward the northeast from Piney Prospect, on what was evidently an inlet in the ancient sea, is a copse of woods on a hillside. Near its center is a cluster of massive rocks, closed on three sides and partially covered overhead by the beetling cliff. In this dismal retreat a runaway slave, named Tom Morgan, lay hidden for many months, emerging at night to subsist by robbery. Such terror was caused by his depredations that a force of men, armed with shotguns, scoured the forest, succeeded in finding the hiding place and capturing the robber. This is the "Robber's Den" or "Black Tom's Lair." With boyish curiosity I visited it the day after his capture and gazed with awe and pity on his bed of leaves, his shoemaker's bench, the charred firelogs and the bones of pigs and fowls, relics of his lawless life. He ran away because he had been sold to a speculator and was un-willing to be carried to a distant Southern plantation."

Okay, long quote. So the questions are: Where is the Robber's Den? Does anyone know of any other source that mentions this incident?

When Battle mentions Point Prospect, he means, of course, the overlook to the east from the vicnity of Gimghoul Castle. A mile to the northeast of there "on a hillside" would seem to be somewhere on the hill that is the Greenwood neighborhood in Chapel Hill. Near Paul Green's house? I don't know. There is a lot of private land back there and it would take the permission of a lot of landowners to really explore the area.

According to Wikipedia, Battle was born in 1831 and graduated from UNC in 1849 (at the age of 18?). So I take it that the capture (and presumable execution) of poor Tom Morgan must have occurred in the 1840's some time. I wonder if these events were ever mentioned in the Hillsborough Recorder?

"About a mile toward the northeast from Piney Prospect, on what was evidently an inlet in the ancient sea, is a copse of woods on a hillside. Near its center is a cluster of massive rocks, closed on three sides and partially covered overhead by the beetling cliff. In this dismal retreat a runaway slave, named Tom Morgan, lay hidden for many months, emerging at night to subsist by robbery. Such terror was caused by his depredations that a force of men, armed with shotguns, scoured the forest, succeeded in finding the hiding place and capturing the robber. This is the "Robber's Den" or "Black Tom's Lair." With boyish curiosity I visited it the day after his capture and gazed with awe and pity on his bed of leaves, his shoemaker's bench, the charred firelogs and the bones of pigs and fowls, relics of his lawless life. He ran away because he had been sold to a speculator and was un-willing to be carried to a distant Southern plantation."

Okay, long quote. So the questions are: Where is the Robber's Den? Does anyone know of any other source that mentions this incident?

When Battle mentions Point Prospect, he means, of course, the overlook to the east from the vicnity of Gimghoul Castle. A mile to the northeast of there "on a hillside" would seem to be somewhere on the hill that is the Greenwood neighborhood in Chapel Hill. Near Paul Green's house? I don't know. There is a lot of private land back there and it would take the permission of a lot of landowners to really explore the area.

According to Wikipedia, Battle was born in 1831 and graduated from UNC in 1849 (at the age of 18?). So I take it that the capture (and presumable execution) of poor Tom Morgan must have occurred in the 1840's some time. I wonder if these events were ever mentioned in the Hillsborough Recorder?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)