Here's an interesting description of Swepsonville, NC in the 19th century. It came from The light of four candles by Cardenio Flournoy King (1908). Mr. King's mother was defrauded of her late husbands estate . . .

Sixty miles to the eastward was the little town of Swepsonville, in Alamance County—a Southern cotton-mill town. Mother was forced to go there, that the older children might work. She helped keep the family purse filled by taking boarders. We all worked as soon as we were able. I was a bobbin boy at ten.

There were four hundred hands in the mill, which was a three-story frame structure, and it ran night and day with two shifts. Its machinery was idle only from midnight Saturday night to midnight Sunday night. I was in the night shift. As I remember it, it did not seem to be especially unpleasant. I recall but one painful incident—being knocked across the room by a cruel overseer who found me asleep one night when I should have been at work.

We had religious services every Sunday in the saw-mill, Sunday school and occasional sermons from a Baptist preacher who came from the next town and preached for what he could raise in the collection box. We had singing lessons weekly. This was about the limit of our diversions.

They were good people in that town. Everybody was kind and generous. Everybody was hard-working. I think everybody was religious. The favorite tune sung or whistled was "In the Sweet Bye-and-Bye." I have sometimes wondered, since I grew up, if that was because they had very little to look forward to in this life.

Then came Swepsonville's calamity. The entire population, aroused by the loud clang of the bell on the hill, went up one night and stood in horror, watching the mill burn to the ground.

George W. Swepson, of Raleigh, the owner of the mill, was in town. I knew him quite well, for he boarded at our house when he was in Swepsonville, and I want to depart from the thread of my story just long enough to pay his memory a warm personal tribute. He was a good man, a strong man, a Southern gentleman. He appreciated the humanity of his employees and was interested in them personally. There was none of the soulless magnate about him. The people in his town admired him, respected him and loved him.

I worked my way through the crowd, at eleven or twelve o'clock that night, and stood beside George W. Swepson. Then and there I received my first lesson in bearing up under adversity, in turning defeat into victory. Standing there in the glare of the burning mill, which meant a terrible loss to him, Mr. Swepson made a drawing for the new mill which should be erected upon its ashes, and while the sparks were still shooting heavenward he gave orders to his general superintendent, Monroe Cooke, to order the materials from which the next structure, to be of brick, should be constructed.

This was on Thursday or Friday, and on Monday morning the brick yard was started. Left without a position by the destruction of the mill, I applied for work at the kilns and was given a place as brick bearer, at twenty-five cents a day.

For some weeks I bore brick from the molders to the sun-drying places. I earned a dollar and a half a week and turned it over to my mother. Then there came a day when she realized that the family was not earning enough to support itself. Some of us must go away from home, out into the world where wages were higher and opportunities greater. I was one of those to go and with four dollars in my pocket and my shoes in my carpet-bag I crossed the high bridge and struck out for the railroad and that fortune I never doubted I should some day have.

Saturday, October 24, 2009

Proceedings of the Good Roads Institute 1911

Continuing our NC Piedmont travel description series, here is the relevant portion of the Proceedings of the Good Roads Institute 1911, by Joseph Hyde Pratt and Hattie M. Berry:

From Durham to Graham, Alamance County, two routes are available —one, via Hillsboro (see Fig. 2), the county seat of Orange County, and the other, via Chapel Hill (see Fig. 3), Orange County.

[Fig.2 is essentially Old NC 10/US 70; Fig. 3 is Old Chapel Hill-Durham Road, just south of US 15-501]

At the present time the best route is via Chapel Hill. From Durham to the Orange County line the road is macadam and from the line to Chapel Hill it is sand-clay. There are a great many beautiful vistas along this road, and, when within one mile of Chapel Hill and immediately after crossing an iron bridge [Bolin Creek], the road begins to climb a long hill [Strowd Hill on Franklin Street in CH] (on an easy grade, however), which is the first hill climbing of any extent that the traveler has encountered since leaving Morehead City. When the top of the hill is reached a splendid view greets the traveler, and he can see across the broad valley nearly as far as Raleigh.

Chapel Hill, the seat of the State University, is located on the summit of a long, high hill, and the highway passes through the main street of the town. Entering from the east, the broad street, with its beautiful homes and well-kept yards on each side, gives some idea of the beauty and dignity of this delightful old town. Sufficient time should be taken to ride through the campus of the oldest State University in the country. Just before reaching the center of the town, the Episcopal Church will be passed. This beautiful, ivy-covered building [Chapel of the Cross] attracts the attention of all who pass and reminds one of old English churches. It was designed by Upjohn, the architect who designed Old Trinity Church of New York.

As one leaves Chapel Hill and rides toward Saxapahaw, Alamance County, he realizes that he has entered the rolling and hilly country of the Piedmont Plateau region. [No mention of Carrboro!]The highway, however, will take the hills by easy grades and the scenery claims the attention of the traveler for the whole distance. [Just as true 98 years later!] At Saxapahaw the road twines down to Haw River, which is crossed on an iron bridge. This little mill town, situated about 9 miles from a railroad, is a city unto itself.

The road from Saxapahaw to Graham has just been completed and is partly sand-clay and partly macadam.

The other route from Durham to Graham, via Hillsboro, passes through West Durham, where the large Methodist College (Trinity) [Duke University, obviously] is located. The road to the Durham line will be macadam and across Orange County it will be gravel or sand-clay. [This is Old NC 10/US 70.] Within a few miles of Hillsboro the road passes through two of the noted farms of the State, the Duke farm and the Occoneechee farm. Hillsboro was formerly the capital of the State, and contains many very attractive old homes.

Cornwallis began the construction of paved roads at Hillsboro during the year 1780 of the Revolutionary War, when he had his army quartered for the winter at that place. At the time the roads were practically impassable and he had his soldiers fill the mudholes with rocks. While it did not make a smooth or good road, it did make them passable, so that he was able to haul his cannon and wagons. Some of Cornwallis's road improvement is still to be seen. Most of it, however, has been replaced recently by a good macadam. This old historic town is well worth a visit by the tourist, and most delightful accommodations can be had at the Corbinton Inn.

On leaving Hillsboro the road to Mebane is very hilly and rough, but a new location has been made and the new road should be finished within the next year.

At nearly every town that the highway passes through since leaving Raleigh are one or more cotton mills, and these mills continue to be conspicuous landmarks until the highway passes Mooresville and Statesville. At West Durham the Erwin Cotlon Mills represent the largest in the South and one of them covers a greater area than any other cotton mill in the country.

At Mebane is the plant of the White Furniture Company. This is the beginning of a series of furniture factories that will be observed in many of the towns from this point westward. From Mebane the highway passes through Haw River to Graham, where it intersects with the Chapel Hill road. On leaving Graham the traveler will find a splendid macadam road for a distance of 50 miles, passing through Burlington and Elon College, Alamance County, and Gibsonville, Greensboro, Jamestown, and High Point, Guilford County.

At Greensboro, the county seat of Guilford County, the Central Highway intersects the National Highway and the two highways coincide as far as Landis, Rowan County, 62 miles to the south. Good hotel accom- ' modations can be obtained in Greensboro, at the Guilford and McAdoo hotels. The State Normal College, the Greensboro Female College, and the A. and M. College for the colored race are located in this city. Guilford County received the $1,000 offered by the Atlanta Journal for the county south of Roanoke, Virginia, through which the National Highway passed that had the best roads. The county is keeping up its reputation and still has the best system of roads of any county in the State. The macadam road between Greensboro and High Point, 15 miles, has been treated with tarvia.

It was only a few years ago that High Point was a small village whose only distinction was the fact that it was the highest point on the Southern Railway between Danville and Charlotte. Now it is the second city in the country in the manufacture of furniture, the only city exceeding it being Grand Rapids, Michigan. Soon after leaving High Point the Highway enters Davidson County, and the roads during rainy weather have caused travelers a great many anxious moments. The route through this country has recently been resurveyed and the long hills have been eliminated. Revenue will also be available to convert the heavy clay road into a beautiful, smooth, sand-clay road.

People who have driven across Davidson County have not had an opportunity to appreciate the beauties of the county, as their thoughts have been too much centered on the road. Another six months will see the road in good condition, and then the traveler will realize that he is passing through a most delightful section of the State, where productive and prosperous farms are very numerous, and, with the beautiful views from the ridge and up the long rich valleys, will impress one that this county is one in which it would be good to live. Thomasville and the county seat, Lexington, are two rapidly growing towns of this section. Lexington Township has recently issued $100,000 in bonds for the construction of good roads.

Just before reaching the Yadkin River, which is the boundary line between Davidson and Rowan counties, the highway passes near the Daniel Boone Memorial Cabin, which marks the birthplace of that great American pioneer and noted character in American history. Yadkin River is crossed by a tollbridge, but plans are now under way to have a free bridge across this river. At the time of the Automobile Run from !N"ew York to Atlanta under the auspices of the New York Herald and the Atlanta Journal, this tollgate at the end of the bridge was the only tollgate that was raised without charging the tourists toll.

First-class sand-clay and macadam roads are again encountered as the highway reaches Rowan County. The steep hill immediately beyond the bridge will soon be a thing of the past. A new location has been surveyed for the highway, and the new road will be ready by spring. For the next 50 to 60 miles the highway is a joy to all who ride over it, smooth surface and easy grades. Spencer, where are located the large shops of the Southern Railway, is soon passed and Salisbury is in sight. This town, the county seat of Rowan County, is of historic interest in connection with scenes enacted during the Civil War. One of the Confederate prisons was located here. One of the Federal cemeteries is at Salisbury, and, during the past few years, several very handsome monuments have been erected by Northern States to the memory of their soldiers buried at this place.

From Durham to Graham, Alamance County, two routes are available —one, via Hillsboro (see Fig. 2), the county seat of Orange County, and the other, via Chapel Hill (see Fig. 3), Orange County.

[Fig.2 is essentially Old NC 10/US 70; Fig. 3 is Old Chapel Hill-Durham Road, just south of US 15-501]

At the present time the best route is via Chapel Hill. From Durham to the Orange County line the road is macadam and from the line to Chapel Hill it is sand-clay. There are a great many beautiful vistas along this road, and, when within one mile of Chapel Hill and immediately after crossing an iron bridge [Bolin Creek], the road begins to climb a long hill [Strowd Hill on Franklin Street in CH] (on an easy grade, however), which is the first hill climbing of any extent that the traveler has encountered since leaving Morehead City. When the top of the hill is reached a splendid view greets the traveler, and he can see across the broad valley nearly as far as Raleigh.

Chapel Hill, the seat of the State University, is located on the summit of a long, high hill, and the highway passes through the main street of the town. Entering from the east, the broad street, with its beautiful homes and well-kept yards on each side, gives some idea of the beauty and dignity of this delightful old town. Sufficient time should be taken to ride through the campus of the oldest State University in the country. Just before reaching the center of the town, the Episcopal Church will be passed. This beautiful, ivy-covered building [Chapel of the Cross] attracts the attention of all who pass and reminds one of old English churches. It was designed by Upjohn, the architect who designed Old Trinity Church of New York.

As one leaves Chapel Hill and rides toward Saxapahaw, Alamance County, he realizes that he has entered the rolling and hilly country of the Piedmont Plateau region. [No mention of Carrboro!]The highway, however, will take the hills by easy grades and the scenery claims the attention of the traveler for the whole distance. [Just as true 98 years later!] At Saxapahaw the road twines down to Haw River, which is crossed on an iron bridge. This little mill town, situated about 9 miles from a railroad, is a city unto itself.

The road from Saxapahaw to Graham has just been completed and is partly sand-clay and partly macadam.

The other route from Durham to Graham, via Hillsboro, passes through West Durham, where the large Methodist College (Trinity) [Duke University, obviously] is located. The road to the Durham line will be macadam and across Orange County it will be gravel or sand-clay. [This is Old NC 10/US 70.] Within a few miles of Hillsboro the road passes through two of the noted farms of the State, the Duke farm and the Occoneechee farm. Hillsboro was formerly the capital of the State, and contains many very attractive old homes.

Cornwallis began the construction of paved roads at Hillsboro during the year 1780 of the Revolutionary War, when he had his army quartered for the winter at that place. At the time the roads were practically impassable and he had his soldiers fill the mudholes with rocks. While it did not make a smooth or good road, it did make them passable, so that he was able to haul his cannon and wagons. Some of Cornwallis's road improvement is still to be seen. Most of it, however, has been replaced recently by a good macadam. This old historic town is well worth a visit by the tourist, and most delightful accommodations can be had at the Corbinton Inn.

On leaving Hillsboro the road to Mebane is very hilly and rough, but a new location has been made and the new road should be finished within the next year.

At nearly every town that the highway passes through since leaving Raleigh are one or more cotton mills, and these mills continue to be conspicuous landmarks until the highway passes Mooresville and Statesville. At West Durham the Erwin Cotlon Mills represent the largest in the South and one of them covers a greater area than any other cotton mill in the country.

At Mebane is the plant of the White Furniture Company. This is the beginning of a series of furniture factories that will be observed in many of the towns from this point westward. From Mebane the highway passes through Haw River to Graham, where it intersects with the Chapel Hill road. On leaving Graham the traveler will find a splendid macadam road for a distance of 50 miles, passing through Burlington and Elon College, Alamance County, and Gibsonville, Greensboro, Jamestown, and High Point, Guilford County.

At Greensboro, the county seat of Guilford County, the Central Highway intersects the National Highway and the two highways coincide as far as Landis, Rowan County, 62 miles to the south. Good hotel accom- ' modations can be obtained in Greensboro, at the Guilford and McAdoo hotels. The State Normal College, the Greensboro Female College, and the A. and M. College for the colored race are located in this city. Guilford County received the $1,000 offered by the Atlanta Journal for the county south of Roanoke, Virginia, through which the National Highway passed that had the best roads. The county is keeping up its reputation and still has the best system of roads of any county in the State. The macadam road between Greensboro and High Point, 15 miles, has been treated with tarvia.

It was only a few years ago that High Point was a small village whose only distinction was the fact that it was the highest point on the Southern Railway between Danville and Charlotte. Now it is the second city in the country in the manufacture of furniture, the only city exceeding it being Grand Rapids, Michigan. Soon after leaving High Point the Highway enters Davidson County, and the roads during rainy weather have caused travelers a great many anxious moments. The route through this country has recently been resurveyed and the long hills have been eliminated. Revenue will also be available to convert the heavy clay road into a beautiful, smooth, sand-clay road.

People who have driven across Davidson County have not had an opportunity to appreciate the beauties of the county, as their thoughts have been too much centered on the road. Another six months will see the road in good condition, and then the traveler will realize that he is passing through a most delightful section of the State, where productive and prosperous farms are very numerous, and, with the beautiful views from the ridge and up the long rich valleys, will impress one that this county is one in which it would be good to live. Thomasville and the county seat, Lexington, are two rapidly growing towns of this section. Lexington Township has recently issued $100,000 in bonds for the construction of good roads.

Just before reaching the Yadkin River, which is the boundary line between Davidson and Rowan counties, the highway passes near the Daniel Boone Memorial Cabin, which marks the birthplace of that great American pioneer and noted character in American history. Yadkin River is crossed by a tollbridge, but plans are now under way to have a free bridge across this river. At the time of the Automobile Run from !N"ew York to Atlanta under the auspices of the New York Herald and the Atlanta Journal, this tollgate at the end of the bridge was the only tollgate that was raised without charging the tourists toll.

First-class sand-clay and macadam roads are again encountered as the highway reaches Rowan County. The steep hill immediately beyond the bridge will soon be a thing of the past. A new location has been surveyed for the highway, and the new road will be ready by spring. For the next 50 to 60 miles the highway is a joy to all who ride over it, smooth surface and easy grades. Spencer, where are located the large shops of the Southern Railway, is soon passed and Salisbury is in sight. This town, the county seat of Rowan County, is of historic interest in connection with scenes enacted during the Civil War. One of the Confederate prisons was located here. One of the Federal cemeteries is at Salisbury, and, during the past few years, several very handsome monuments have been erected by Northern States to the memory of their soldiers buried at this place.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Fur Craig’s

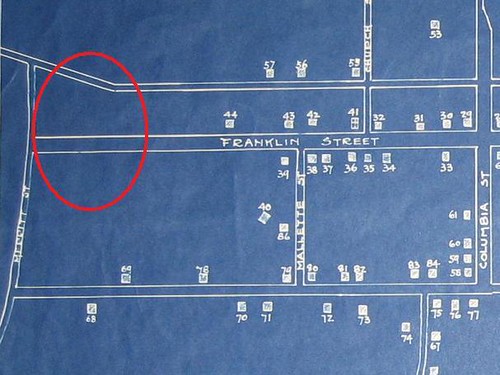

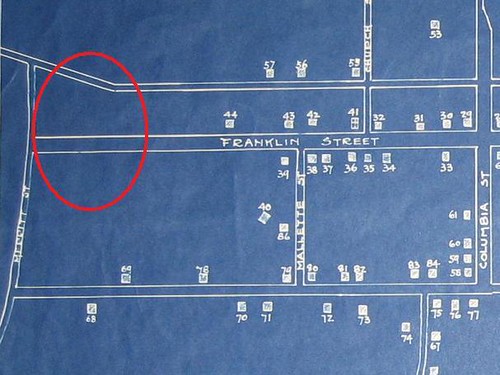

In 1792, as the University Trustees were deciding where to establish UNC, local farmers offered up over 1,000 acres to entice UNC to Chapel Hill. Among the ten land donors, the smallest was John Craig, who donated just 5 acres. The Craig donation was that funny crook in the western boundary of the original University lands:

Although John Craig donated only 5 acres, his family clearly owned some other land nearby. James Craig's farmhouse was known to the early students of the University as Fur Craig’s, as both Battle’s History and Hooper’s Tis Fifty Years Since tell us. It was called Fur Craig’s, as Battle says, “in distinction from the habitation of a man of the same name on the Durham road.” That is, it was not Near Craig’s; it was Fur Craig's. This picture from Steve Rankin is said to be Fur Craig's:

Battle hints at the location of Fur Craig’s: “James Craig lived in the house still [ie in 1910] occupied by one of his descendants in the extreme western part of the village . . . a favorite boarding house for those not adverse to long walks . . . a farm house a mile from the town.” Battle’s description would seem to place Fur Craig’s somewhere near Merritt Mill Road, nearly in what is now Carrboro.

The legal description of Alexander Piper's 1793 land donation to UNC (20 acres in what would later become downtown Carrboro) reads: “beginning at a post oak, James Craig's corner, thence West 80 poles . . .” clearly indicating that Craig’s land was just east of the Piper donation, which would place it just east of Carr Mill Mall.

UNC sold the Piper donation to James Craig's son, John M. Craig, in 1837 (Orange DB 28, pg 272). And John M. Craig sold a larger parcel in 1867 “lying on the western outskirts of Chapel Hill upon both sides of the road leading from Chapel Hill to Greensboro adjoining the lands of John Weaver, Thomas Weaver . . . beginning at the mud hole in Craigs Lane . . . to a locust on the road leading to Greensboro . . . to a rock in the road from Chapel Hill to Jones Ford on Haw River . . . containing 101 ½ acres more or less." So the property straddled Weaver Street (the road leading to Gboro) and was bounded on the south by Jones Ferry Road (the road from CH to Jones Ford). This must have constituted most of downtown Carrboro, including the Piper donation and then some.

But it is also clear that the John M. Craig tract was not “Fur Craig’s” as Battle mentions that the Craig’s still lived there in 1910, whereas John M Craig sold that tract in 1867. Also an 1879 further conveyance of the John M Craig tract to Henry H Patterson and Fendal S Hogan (ODB 46, pg 257) mentions specifically that James F. Craig owned land just to the east. Battle tells us: “James Francis Craig, his [James Craig’s] grandson, a student of the University in 1852, recently [1910] died on the old homestead.” Also, I believe James F. Craig was a member of the Chapel Hill Board of Commissioners (now Town Council) in the 1880’s, suggesting the Fur Craig’s may have been within town limits in the 1880's (ie east of Merritt Mill Road.)

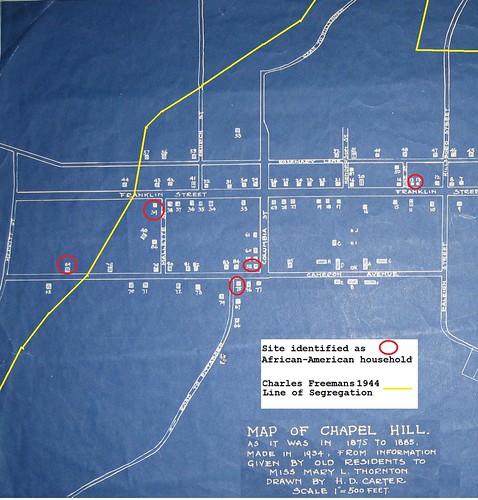

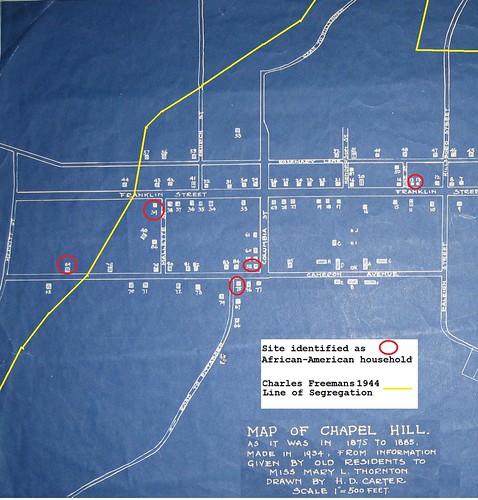

So the upshot of that would seem to be that Fur Craig’s must have been somewhere east of Merritt Mill Road, more or less in the vicinity of what is now Greenbridge. However, the Map of Chapel Hill as it was 1875-1885 shows no dwelling in that area:

Although John Craig donated only 5 acres, his family clearly owned some other land nearby. James Craig's farmhouse was known to the early students of the University as Fur Craig’s, as both Battle’s History and Hooper’s Tis Fifty Years Since tell us. It was called Fur Craig’s, as Battle says, “in distinction from the habitation of a man of the same name on the Durham road.” That is, it was not Near Craig’s; it was Fur Craig's. This picture from Steve Rankin is said to be Fur Craig's:

Battle hints at the location of Fur Craig’s: “James Craig lived in the house still [ie in 1910] occupied by one of his descendants in the extreme western part of the village . . . a favorite boarding house for those not adverse to long walks . . . a farm house a mile from the town.” Battle’s description would seem to place Fur Craig’s somewhere near Merritt Mill Road, nearly in what is now Carrboro.

The legal description of Alexander Piper's 1793 land donation to UNC (20 acres in what would later become downtown Carrboro) reads: “beginning at a post oak, James Craig's corner, thence West 80 poles . . .” clearly indicating that Craig’s land was just east of the Piper donation, which would place it just east of Carr Mill Mall.

UNC sold the Piper donation to James Craig's son, John M. Craig, in 1837 (Orange DB 28, pg 272). And John M. Craig sold a larger parcel in 1867 “lying on the western outskirts of Chapel Hill upon both sides of the road leading from Chapel Hill to Greensboro adjoining the lands of John Weaver, Thomas Weaver . . . beginning at the mud hole in Craigs Lane . . . to a locust on the road leading to Greensboro . . . to a rock in the road from Chapel Hill to Jones Ford on Haw River . . . containing 101 ½ acres more or less." So the property straddled Weaver Street (the road leading to Gboro) and was bounded on the south by Jones Ferry Road (the road from CH to Jones Ford). This must have constituted most of downtown Carrboro, including the Piper donation and then some.

But it is also clear that the John M. Craig tract was not “Fur Craig’s” as Battle mentions that the Craig’s still lived there in 1910, whereas John M Craig sold that tract in 1867. Also an 1879 further conveyance of the John M Craig tract to Henry H Patterson and Fendal S Hogan (ODB 46, pg 257) mentions specifically that James F. Craig owned land just to the east. Battle tells us: “James Francis Craig, his [James Craig’s] grandson, a student of the University in 1852, recently [1910] died on the old homestead.” Also, I believe James F. Craig was a member of the Chapel Hill Board of Commissioners (now Town Council) in the 1880’s, suggesting the Fur Craig’s may have been within town limits in the 1880's (ie east of Merritt Mill Road.)

So the upshot of that would seem to be that Fur Craig’s must have been somewhere east of Merritt Mill Road, more or less in the vicinity of what is now Greenbridge. However, the Map of Chapel Hill as it was 1875-1885 shows no dwelling in that area:

The Life of Edmund Fanning

Benson Lossing’s Pictorial Fieldbook of the Revolution includes a convenient sketch of the life of Edmund Fanning, which I thought would make a nice post on the blog. Foremost, note that Edmund Fanning is more or less no relation to the infamous Tory raider Col. David Fanning of Randolph County fame. Edmund was a notorious lawyer and loyalist who was hated by the Regulators. He was just the sort of person that John F D Stuart-Smyth was referring to when he wrote that before the Revolution some in Orange County became wealthy “by the practice of law, which in this province is peculiarly lucrative and extremely oppressive.”

Here’s Lossing’s sketch [with my comments in square brackets]:

Edmund Fanning was a native of Long Island, New York, son of Colonel Phineas Fanning. [He was Southold, Long Island per wikipedia; also the Canadian Dictionary of Biography says he was the son of James Fanning and Hannah Smith.] He was educated at Yale College, and graduated with honor in 1757. He soon afterward [1761] went to North Carolina, and began the profession of a lawyer at Hillsborough, then called Childsborough. In 1760, the degree of L.L.D. was conferred upon him by his alma mater. In 1763, he was appointed colonel of Orange county, and in 1765 was made clerk of the Superior Court at Hillsborough. He also represented Orange county in the Colonial Legislature. In common with other lawyers, he appears to have exacted exorbitant fees for legal services, and consequently incurred the dislike of the people, which was finally manifested by acts of violence. He accompanied Governor Tryon to New York, in 1771, as his secretary. Governor Martin asked the Legislature to indemnify Colonel Fanning for his losses; the representatives of the people rebuked the governor for presenting such a petition. In 1776, General Howe gave Fanning the commission of colonel, and he raised and commanded a corps called the King's American Regiment of Foot. He was afterward appointed to the lucrative office of surveyor general, which he retained until his flight, with other Loyalists, to Nova Scotia, in 1783. In 1786 he was made lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia, and in 1794 he was appointed governor of Prince Edward's Island. He held the latter office about nineteen years, a part of which time he was also a brigadier in the British army, having received his commission in 1808. He married in Nova Scotia, where some of his family yet reside. General Fanning died in London, in 1818, at the age of about eighty-one years. His widow and two daughters yet (1852) survive. One daughter, Lady Wood, a widow, resides near London with her mother; the other, wife of Captain Bentwick Cumberland, a nephew of Lord Bentwick, resides at Charlotte's Town, New Brunswick. I am indebted to John Fanning Watson, Esq., the Annalist of Philadelphia and New York, for the portrait here given.

General Fanning's early career, while in North Carolina, seems not to have given promise of that life of usefulness which he exhibited after leaving Republican America. It has been recorded, it is true, by partisan pens, yet it is said that he often expressed regrets for his indiscreet course at Hillsborough. His after life bore no reproaches, and the Gentlemen's Magazine (1818), when noting his death, remarked, "The world contained no better man in all the relations of life." [Although it should be noted that almost all 19th century obituaries have a hagiographic aspect to them.]

Here’s Lossing’s sketch [with my comments in square brackets]:

Edmund Fanning was a native of Long Island, New York, son of Colonel Phineas Fanning. [He was Southold, Long Island per wikipedia; also the Canadian Dictionary of Biography says he was the son of James Fanning and Hannah Smith.] He was educated at Yale College, and graduated with honor in 1757. He soon afterward [1761] went to North Carolina, and began the profession of a lawyer at Hillsborough, then called Childsborough. In 1760, the degree of L.L.D. was conferred upon him by his alma mater. In 1763, he was appointed colonel of Orange county, and in 1765 was made clerk of the Superior Court at Hillsborough. He also represented Orange county in the Colonial Legislature. In common with other lawyers, he appears to have exacted exorbitant fees for legal services, and consequently incurred the dislike of the people, which was finally manifested by acts of violence. He accompanied Governor Tryon to New York, in 1771, as his secretary. Governor Martin asked the Legislature to indemnify Colonel Fanning for his losses; the representatives of the people rebuked the governor for presenting such a petition. In 1776, General Howe gave Fanning the commission of colonel, and he raised and commanded a corps called the King's American Regiment of Foot. He was afterward appointed to the lucrative office of surveyor general, which he retained until his flight, with other Loyalists, to Nova Scotia, in 1783. In 1786 he was made lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia, and in 1794 he was appointed governor of Prince Edward's Island. He held the latter office about nineteen years, a part of which time he was also a brigadier in the British army, having received his commission in 1808. He married in Nova Scotia, where some of his family yet reside. General Fanning died in London, in 1818, at the age of about eighty-one years. His widow and two daughters yet (1852) survive. One daughter, Lady Wood, a widow, resides near London with her mother; the other, wife of Captain Bentwick Cumberland, a nephew of Lord Bentwick, resides at Charlotte's Town, New Brunswick. I am indebted to John Fanning Watson, Esq., the Annalist of Philadelphia and New York, for the portrait here given.

General Fanning's early career, while in North Carolina, seems not to have given promise of that life of usefulness which he exhibited after leaving Republican America. It has been recorded, it is true, by partisan pens, yet it is said that he often expressed regrets for his indiscreet course at Hillsborough. His after life bore no reproaches, and the Gentlemen's Magazine (1818), when noting his death, remarked, "The world contained no better man in all the relations of life." [Although it should be noted that almost all 19th century obituaries have a hagiographic aspect to them.]

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

Sketch of the Life of the Rev. Dr. Alexander Wilson

Rev. Dr. Alexander Wilson's father was reportedly a wealthy man in Ireland who is said to have lost his fotune as a result of acting as a guarantor of the debts of others. It is said that the father was also named Alexander Wilson. But Rev. Alexander Wilson was called Alexander Wilson, Sr. and his son was Alexander, Jr., so it seems unlikely that the Reverend's father was also named Alexander.

In any case, the subject of this sketch was born in 1799 in County Down, Ireland, at Ballylesson. The younger Alexander Wilson grew up in Ireland, studying to become a physician. Around 1817 he graduated from Apothecaries Hall, Dublin. Wilson probably married shortly after graduation. In July 1818 he immigrated to America. Some sources say he lived for a time in New York and taught school there, but others say that North Carolina was his only state of residence in America.

Soon his wife, Mary, came to America as well and about 1820 they were in Raleigh, North Carolina. Wilson taught under Rev. William McPheeters at Raleigh Academy for a year, but then took up teaching in 1821 in Granville County at Williamsboro Academy. In 1826, Wilson was granted his United States citizenship by the Granville County Court. Wilson worked for many years in Granville County, living in Oak Hill. He was the Presbyterian minister to several congregations, including Grassy Creek Presbyterian (which moved and is now Oak Hill Presb.) and Nut Bush Presbyterian which was in the community of Williamsboro. Williamsboro is now called ___ and is in that part of old Granville County which is Vance County today. Rev. Wilson also attended the 1833 founding of Geneva Presbyterian Church in Granville County, as well as probably others.

Rev. Wilson’s work in Granville County was done under the auspices of the New Hope Presbytery. Later, Rev. Wilson became involved in the Orange Presbytery. I don’t know whether this reflects any ideological difference between these Presbyteries. The Grassy Creek Presbyterian Church history notes: “[T]he first African Americans admitted into membership of the Church was between 1833-34. In 1835 service began to be held also in a meeting house between Oak Hill and the Virginia Line, near the residence of the late Graham E. Royster.” This change occurred shortly before Wilson left the New Hope Presbytery, but it is unclear whether these events are related.

In 1833 the Orange Presbytery appointed Rev. Wilson to a committee on Presbyterian education, along with UNC Pres. David Caldwell and a number of others. The committee concluded that a Presbyterian school was needed. The Presbytery concurred and the Caldwell Institute was founded in Greensboro in 1836 with Rev. Wilson as Principal. Mary Wilson initially remained in Granville County, but probably moved to Greensboro around 1837 or 1838.

Around 1845 there was apparently an epidemic in Greensboro and so it was decided to move the school. In the summer of 1845 the Presbytery decided to move the school to Hillsborough and Rev. Wilson moved with the school. About 1850, the Caldwell Institute moved again to the vicinity of Little River Presbyterian Church northeast of Hillsborough, but Wilson did not move with it.

Rev. Wilson’s sons were James, Robert and Alexander, Jr. Robert and Alexander helped teach at their father’s school. Maj. James W. Wilson became a railroad commissioner and Robert Wilson became a businessman in Richmond, Virginia. The Wilson’s also had two daughters, one of whom died young and the other of whom, Alice E. Wilson, married Edwin A. Heartt in late 1847 (Q-H/709), the son of Hillsboro Recorder editor Dennis Heartt.

Right about the same time that Alice Wilson and Edwin Heartt were married, Rev. Wilson, his son Alexander, Jr. and Edwin Heartt bought 50 acres just north of Swepsonville in the community then known as Burnt Shop (ODB 33, pp 101-104). This site was formerly part of 300 acres conveyed from Samuel Child to John W. Norwood (deed not recorded) and was east of the land of the widow of Stephen Glass. At the same time, John A. Bingham bought an additional 50 acres, also formerly part of the Child-Norwood tract.

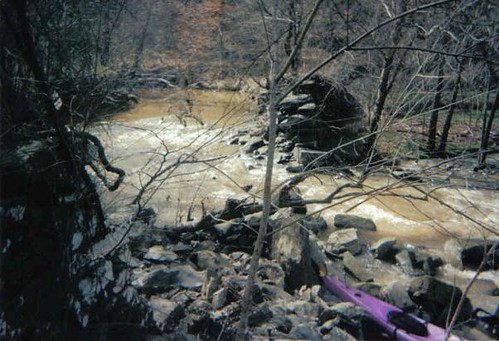

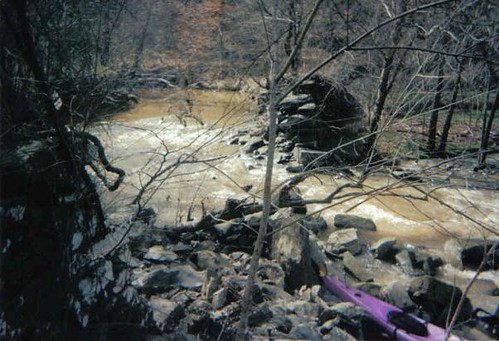

In 1851, Rev. Wilson founded his own three-room school in Burnt Shop. It is has been claimed that Henderson Scott of the Hawfields was influential in getting Wilson to choose Burnt Shop as the location for the school. If so, then those conversations must have been on-going almost from the moment that Rev. Wilson moved to Hillsborough. In any case, Wilson renamed the community after the Scotch theologian Andrew Melville. The Alexander Wilson School or Melville School became the primary fixture of Melville and earned a reputation as an excellent school. Rev. Wilson also built a gristmill on Haw Creek under the supervision of millwright Berry Davidson. However the dam was ruptured in a great flood in 1875. The remains of the dam can still be seen about 1 mile downstream of the NC 54 bridge over Haw Creek:

Rev. Wilson’s students included several members of the Morehead family, Turner Tate, Tom Roulhac, John and James Wilson, William Mebane, T. B. Bailey, John W. and Geo. Bason, L. Banks Holt, Lawrence Holt, Samuel K. Scott, J. R. Newlin, and Mayor Van Wyck, of New York. After his death in 1867, the school soon closed, but the community is still known as Melville today; and the modern public school in Melville is still called the Alexander Wilson Elementary School.

In any case, the subject of this sketch was born in 1799 in County Down, Ireland, at Ballylesson. The younger Alexander Wilson grew up in Ireland, studying to become a physician. Around 1817 he graduated from Apothecaries Hall, Dublin. Wilson probably married shortly after graduation. In July 1818 he immigrated to America. Some sources say he lived for a time in New York and taught school there, but others say that North Carolina was his only state of residence in America.

Soon his wife, Mary, came to America as well and about 1820 they were in Raleigh, North Carolina. Wilson taught under Rev. William McPheeters at Raleigh Academy for a year, but then took up teaching in 1821 in Granville County at Williamsboro Academy. In 1826, Wilson was granted his United States citizenship by the Granville County Court. Wilson worked for many years in Granville County, living in Oak Hill. He was the Presbyterian minister to several congregations, including Grassy Creek Presbyterian (which moved and is now Oak Hill Presb.) and Nut Bush Presbyterian which was in the community of Williamsboro. Williamsboro is now called ___ and is in that part of old Granville County which is Vance County today. Rev. Wilson also attended the 1833 founding of Geneva Presbyterian Church in Granville County, as well as probably others.

Rev. Wilson’s work in Granville County was done under the auspices of the New Hope Presbytery. Later, Rev. Wilson became involved in the Orange Presbytery. I don’t know whether this reflects any ideological difference between these Presbyteries. The Grassy Creek Presbyterian Church history notes: “[T]he first African Americans admitted into membership of the Church was between 1833-34. In 1835 service began to be held also in a meeting house between Oak Hill and the Virginia Line, near the residence of the late Graham E. Royster.” This change occurred shortly before Wilson left the New Hope Presbytery, but it is unclear whether these events are related.

In 1833 the Orange Presbytery appointed Rev. Wilson to a committee on Presbyterian education, along with UNC Pres. David Caldwell and a number of others. The committee concluded that a Presbyterian school was needed. The Presbytery concurred and the Caldwell Institute was founded in Greensboro in 1836 with Rev. Wilson as Principal. Mary Wilson initially remained in Granville County, but probably moved to Greensboro around 1837 or 1838.

Around 1845 there was apparently an epidemic in Greensboro and so it was decided to move the school. In the summer of 1845 the Presbytery decided to move the school to Hillsborough and Rev. Wilson moved with the school. About 1850, the Caldwell Institute moved again to the vicinity of Little River Presbyterian Church northeast of Hillsborough, but Wilson did not move with it.

Rev. Wilson’s sons were James, Robert and Alexander, Jr. Robert and Alexander helped teach at their father’s school. Maj. James W. Wilson became a railroad commissioner and Robert Wilson became a businessman in Richmond, Virginia. The Wilson’s also had two daughters, one of whom died young and the other of whom, Alice E. Wilson, married Edwin A. Heartt in late 1847 (Q-H/709), the son of Hillsboro Recorder editor Dennis Heartt.

Right about the same time that Alice Wilson and Edwin Heartt were married, Rev. Wilson, his son Alexander, Jr. and Edwin Heartt bought 50 acres just north of Swepsonville in the community then known as Burnt Shop (ODB 33, pp 101-104). This site was formerly part of 300 acres conveyed from Samuel Child to John W. Norwood (deed not recorded) and was east of the land of the widow of Stephen Glass. At the same time, John A. Bingham bought an additional 50 acres, also formerly part of the Child-Norwood tract.

In 1851, Rev. Wilson founded his own three-room school in Burnt Shop. It is has been claimed that Henderson Scott of the Hawfields was influential in getting Wilson to choose Burnt Shop as the location for the school. If so, then those conversations must have been on-going almost from the moment that Rev. Wilson moved to Hillsborough. In any case, Wilson renamed the community after the Scotch theologian Andrew Melville. The Alexander Wilson School or Melville School became the primary fixture of Melville and earned a reputation as an excellent school. Rev. Wilson also built a gristmill on Haw Creek under the supervision of millwright Berry Davidson. However the dam was ruptured in a great flood in 1875. The remains of the dam can still be seen about 1 mile downstream of the NC 54 bridge over Haw Creek:

Rev. Wilson’s students included several members of the Morehead family, Turner Tate, Tom Roulhac, John and James Wilson, William Mebane, T. B. Bailey, John W. and Geo. Bason, L. Banks Holt, Lawrence Holt, Samuel K. Scott, J. R. Newlin, and Mayor Van Wyck, of New York. After his death in 1867, the school soon closed, but the community is still known as Melville today; and the modern public school in Melville is still called the Alexander Wilson Elementary School.

Monday, October 12, 2009

Lossing’s Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution

Continuing with my series of blog posts on travelers’ descriptions of their journeys between Hillsborough and Salisbury, North Carolina, I present Benson J. Lossing’s Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution. Lossing traveled all over the east coast visiting and researching important (and not so important) Revolutionary War sites and most of the book is about the history of the Revolutionary War. His account of Greene and Cornwallis’s Race to the Dan is a classic on the topic and is wonderfully detailed, but weaved into that narrative is Lossing’s own narrative about Lossing’s trip from Hillsborough to Salisbury in 1849. Lossing’s penchant for story-telling is delightful. In reproducing his story I have mostly edited out the Revolutionary tales. Those parts of his book are also well worth reading, but they distract from the 1849 narrative.

My comments are in [square brackets]. The more interesting footnotes from Lossing’s book are included here in (parentheses). Enjoy:

I employed the first morning of the new year (1849), in visiting places of interest at Hillsborough, in company with the Reverend Dr. Wilson. [This must have been Alexander Wilson, the schoolmaster of the Caldwell Institute in Hillsborough and later the founder of the Wilson School in Melville, near Swepsonville, NC.] The first object to which my attention was called was a small wooden building, represented in the engraving on the next page, situated opposite the hotel where I was lodged. Cornwallis used it for an office, during his tarryings in Hillsborough, after driving General Greene out of the state. After sketching this, we visited the office of the Clerk of Superior Court, and made the fac similes and extracts from its records, printed on pages 573-4. We next visited the headquarters of Cornwallis, a large frame building situated in the rear of Morris’s Hillsborough House, on King Street. Generals Gates and Greene also occupied it when they were in Hillsborough, and there a large number of the members of the Provincial Congress were generally lodged. The old court-house, where the Regulators performed their lawless acts, is no longer in existence. I was informed by Major Taylor, an octogenarian on whom we called, that it was a brick edifice, and stood almost upon the exact site of the present court-house, which is a spacious brick building, with steeple and clock. The successor of the first was a wooden structure, and being removed to make room for the present building, was converted into a place of meeting for a society of Baptists, who yet worship there. Upon the hill near the Episcopal church, and fronting King Street, is the spot where the Regulators were hung. The residence of Governor Tryon, while in Hillsborough, was on Church Street, a little west of Masonic Hall. These compose the chief objects of historic interest at Hillsborough. The town has other associations connected with the Southern campaigns, but we will not anticipate the revealments of history by considering them now.

At one o’clock I exchanged adieus with the kind Dr. Wilson, crossed the Eno, and , pursuing the route traversed by Tryon on his march to the Allamance, crossed the rapid and now turbid Haw, just below the falls, at sunset [apparently at Swepsonville]. I think I never traveled a worse road than the one stretching between the Eno and the Haw. It passes over a continued series of red clay hills, which are heavily wooded with oaks, gums, black locusts, and chestnuts. Small streams course among these elevations; and in summer this region must be exceedingly picturesque. Now every tree and shrub was leafless, except the holly and the laurel, and nothing green appeared among the wide reaching branches but the beautiful tufts of mistletoe which every where decked the great oaks with their delicate leaves and transparent berries. Two and a half miles beyond the Haw, and eighteen from Hillsborough, I passed the night at Foust’s house of entertainment, and after an early breakfast, rode to the place where Colonel Pyle, a Tory officer, with a considerable body of Loyalists, was deceived and defeated by Lieutenant-colonel Henry Lee and his dragoons, with Colonel Pickens, in the spring of 1781. Dr. Holt, who lives a short distance from that locality, kindly accompanied me to the spot and pointed out the place where the battle occurred; where Colonel Pyle lay concealed in a pond, and where many of the slain were buried. (About a quarter of a mile northwest from this pond, is the spot where the battle occurred. It was then heavily wooded; now it is a cleared field, on the plantation of Colonel Michael Holt. Mr. Holt planted an apple tree upon the spot where fourteen of the slain were buried in one grave. Near by, a persimmon-tree indicates the place of burial of several others. [This footnote is to a part of the text that I omitted, but the note is interesting and relates also to this part of the text, so I included it here.])The place of conflict is about half a mile north of the old Salisbury highway, upon a “plantation road,” two miles east of the Allamance, in Orange county. Let us listen to the voices of history and tradition.

[Here Lossing gives a long and detailed account of Pyle’s Massacre, which I am omitting.]

I left the place of Pyle’s defeat toward noon, and, following a sinuous and seldom traveled road through a forest of wild crab-apple trees and black jacks, crossed the Allamance at the cotton factory of Holt and Carrigan, two miles distant [the village of Alamance]. (This factory, in the midst of a cotton-growing country, and upon a never-failing stream, can not be otherwise than source of great profit to the owners. The machinery is chiefly employed in the manufacture of cotton yarn. Thirteen hundred and fifty spindles were in operation. Twelve loons were employed in the manufacture of coarse cotton goods suitable for the use of the Negroes. [Slaves wore clothes made from a cheap, coarse fabric called osnaburg. The Holt's made mostly osnaburg and a much finer plaid.]) Around this mill quite a village of neat log-houses occupied by the operatives, were collected, and every thing had the appearance of thrift. I went in, and was pleased to see the hands of intelligent white females employed in a useful occupation. Manual labor by white people is a rare sight at the South, where an abundance of slave labor appears to render such occupation unnecessary; and it can seldom be said of one of our fair sisters there, “She layeth her hands to the spindle, and her hands hold the distaff.” This cotton mill, like the few others which I saw in the Carolinas, is a real blessing, present and prospective, for it gives employment and comfort to many poor girls who might otherwise be wretched; and it is a seed of industry planted in a generous soil, which may hereafter germinate and bear abundant fruit of its kind in the midst of cotton plantations, thereby augmenting immensely the true wealth of the nation. [Boy, was he right about that. In 1849, the only other cotton mills in the Haw watershed were at Big Falls (Hopedale) and Saxpahaw. By 1881, there were 12 and by 1900 there were dozens.]

At a distance of two miles and a half beyond the Allamance, on the Salisbury road [more or less NC 62], , I reached the Regulator battle-ground; and, in company with a young man residing in the vicinity, visited the points of particular interest, and a made the sketch printed on page 577. The rock and the ravine from whence James Pugh and his companions (see page 576) did such execution with their rifles, are now hardly visible. The place is a few rods north of the road. The ravine is almost filled by the washing down of earth from the slopes during eighty years; and the rock projects only a few ells above the surface. The whole of the natural scenery is changed, and nothing but tradition can identify the spot. [Almost makes me think that he did not find the right place.]

While viewing the battle-ground, the wind, which had been a gentle and pleasant breeze from the south all the morning, veered to the northeast, and brought omens of a cold storm. I left the borders of the Allamance, and it associations, at one o’clock, and traversing a very hilly country for eighteen miles, arrived, a little after dark, at Greensborough, a thriving, compact village, situated about five miles southeast from the site of old Guilford Court House. It is the capitol of Guilford county, and successor of old Martinsburg, where the court-house was formerly situated. Very few of the villages in the interior of the state appeared to me more like a Northern town than Greensborough. The houses are generally good, and the stores gave evidence of active trade. Within an hour after my arrival, the town was thrown into commotion by the bursting out of flames from a large frame dwelling, a short distance from the court-house. There being no fire-engine in the places, the flames spread rapidly, and at one time menaced the safety of the whole town. A small keg of powder was used, without effect, to demolish a tailor’s shop, standing in the path of the conflagration toward a large tavern. The flames passed on, until confronted by one of those broad chimneys, on the outside of the house, so universally prevalent at the South, when it was subdued, after four buildings were destroyed. I never saw a population more thoroughly frightened; and when I returned to my lodgings, far away from the fire, every bed in the house was packed ready for flight. It was past midnight when the town became quiet, and a consequently late breakfast delayed my departure for the battle-field at Guilford Court House, until nine o’clock the next morning. [It would be interesting to compare this with contemporary press accounts of this fire.]

A cloudy sky, a biting north wind, and the dropping of a few snow-flakes when I left Greensborough, betokened an unpleasant day for my researches. It was ten o’clock when I reached Martinsville, once a pleasant hamlet, now a desolation. There are only a few dilapidated and deserted dwellings left; and nothing remains of the old Guilford Court House but the ruins of a chimney depicted on the plan of the battle, printed on page 608. Only one house was inhabited, and that by the tiller of the soil around it. Descending into a narrow broken valley, from Martinsville, and ascending the opposite slope to still higher ground on the road to Salem, I passed among the fields consecrated by the events of the battle at Guilford, in March, 1781 to the house of Mr. Hotchkiss, a Quaker, who, I was informed could point out every locality of interest in his neighborhood.

Mr. Hotchkiss was absent, and I was obliged to wait more than an hour for his return. The time passed pleasantly in conversation with his daughter, an intelligent young lady, who kindly ordered my horse to be fed, and regaled me with some fine apples, the first fruit of the kind I had seen since leaving the James River. While tarrying there, the snow began to fall thickly, and when, about noon, I rambled over the most interesting portion of the battle-ground, and sketched the scene printed on page 611, the whole country was covered with a white mantle. Here, by this hospitable fireside, let us consider the battle, and those wonderful antecedents events which distinguished General Green’s celebrated Retreat.

[Lossing describes the Race to the Dan and the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in great detail, a wonderful account that I am omitting here.]

I left the Guilford battle-ground and the hospitable cottage of Mr. Hotchkiss, at noon, the snow falling fast. At four miles distant, on the Salisbury road, I reached the venerable New Garden meeting-house, yet standing within the stately oak forest where Lee and Tarleton met. It is a frame building with a brick foundation. It was meeting-day, and the congregation were yet in session. Tying Charley [his horse] to a drooping branch, I entered softly. A larger number than is usually present at “week-day meetings” had congregated, for a young man of the sect from Randolph county, thirty miles distant, and a young woman of Guilford, had signified their intentions to declare themselves publicly on that day, man and wife. [I think it would be straight forward to identify who this couple was.] They had just risen before the elders and people when I glided into a seat near the door, and with a trembling voice the bridegroom had begun the expression of the marriage vow. His weather-bronzed features betokened the man of toil in the fields, and strongly contrasted with the blonde and delicate face, and slender form of her who, with the downcast eyes of modesty, heard his pledge of love and protection, and was summoning all her energy to make her kindred response. I had often observed the simple marriage ceremony of the Quakers, but never before did the beauty of that ritual appear so marked with the sublimity of pure simplicity.

At the close of the meeting, I learned from one of the elders that a Friend’s boarding-school was near, and, led by curiosity, I visited it. [What school is this?] The building is of brick, spacious, and well arranged. It was under the superintendence of Thomas Hunt, a son of Nathan Hunt, an eminent Quaker preacher. An incidental remark concerning my relationship with Quakers, made while conversing with the wife of the superintendent, caused her to inquire whether I had ever heard of here father-in-law. I replied in the affirmative, having heard him preach when I was a boy, and expressed the supposition that he had long ago gone to his rest. “Oh no,” she replied, “he is in the adjoining room,: and leading the way, I was introduced to the patriarch of ninety-one years. He remembered well when the New Garden meetinghouse was built, and resided in the neighborhood when the wounded and dying, from the field of Guilford, were brought there. Although physical infirmities were weighing heavily upon him, his mind appeared clear and elastic. When I was about departing, and pressed his hand with an adieu, he placed the other upon my head and said, “Farewell! God’s peace go with thee!” I felt as if I had received the blessing of a patriarch indeed; and for days afterward, when fording dangerous streams and traversing rough mountain roads, that uttered blessing was in my mind, and seemed like a guardian angel about my path. Gloomy unbelief may deride, and thoughtless levity may laugh in ridicule at such an intimation, but all the philosophy of schools could not give me such exquisite feelings of security in the hands of a kind Providence as that old man’s blessing imparted.

The storm yet continued, and the kind matron of the school gave me a cordial invitation to remain there until it should cease; but, anxious to complete my journey, I rode on to Jamestown, an old village situated upon the high southwestern bank of the Deep River, nine miles from New Garden meeting-house, and thirteen miles above Bell’s Mills, where Cornwallis had his encampment before the Guilford battle. The country through which I had passed from Guilford was very broken, and I did not reach Jamestown until sunset. It is chiefly inhabited by Quakers, the most of them originally from Nantucket and vicinity; and as they do not own slaves, nor employ slave labor, except when a servant is working to purchase his freedom, the land and the dwellings presented an aspect of thrift not visible in most of the agricultural districts in the upper country of the Carolinas.

I passed the night at Jamestown, and early in the morning departed for the Yadkin. Snow was yet falling gently, and it laid three inches deep upon the ground; a greater quantity than had fallen at one time, in that section, for five years. Fortunately my route from thence to Lexington, in Davidson county, a distance of twenty miles, was upon a fine ridge road a greater portion of the way, and the snow produced but little inconvenience. (These ridge roads, or rather ridges upon which they are constructed, are curious features in the upper country of the Carolinas. Although the whole country is hilly upon every side, these roads may be traveled a score of miles, sometimes, with hardly ten feet of variation from a continuous level. The ridges are of sand, and continue, unbroken by ravines, which cleave the hills in all directions for miles, upon almost a uniform level. The roads following their summits are exceedingly sinuous, but being level and hard, the greater distance is more easily accomplished than if they were constructed in straight lines over the hills. The country has the appearance of vast waves of the sea suddenly turned into sand.)

Toward noon, the clouds broke, and before I reached Lexington (a small village on the west side of Abbott’s Creek, a tributary of the Yadkin), at half past two in the afternoon, not a flake of snow remained. Charley and I had already lunched by the margin of a little stream, so I drove through the village without halting, hoping to reach Salisbury, sixteen miles distant, by twilight. I was disappointed; for the red clay roads prevailed, and I only reached the house of a small planted within a mile of the east bank of the Yadkin, just as the twilight gave place to the splendors of a full moon and myriads of stars in a cloudless sky. From the proprietor I learned that the Trading Ford, where Greene and Morgan crossed when pursued by Cornwallis, was only a mile distant. As I could not pass it on my way to Salisbury in the morning, I arose at four o’clock, gave Charley his breakfast and at earliest dawn stood upon the eastern shore of the Yadkin, and made the sketch printed upon page 601. The air was frosty, the pools were bridged with ice, and before the sketch was finished, my benumbed fingers were disposed to drop the pencil. I remained at the ford until the east was all aglow with the radiance of the rising sun, when I walked back, partook of some corn-bread, muddy coffee, and spare-ribs, and at eight o’clock crossed the Yadkin at the great bridge, on the Salisbury road. The river is there about three hundred yards wide, and was considerably swollen from the melting of the recent snows. Its volume of turbid waters came rolling down in a swift current, and gave me a full appreciation of the barrier which Providence had there placed between the Republicans and the royal armies, when engaged in the great race described in this chapter.

From the Yadkin the roads passed through a red clay region, which was made so miry by the melting snows that it was almost eleven o’clock when I arrived at Salisbury. This village, of over a thousand inhabitants, is situated a few miles from the Yadkin, and is the capital of Rowan county, a portion of the “Hornet’s Nest” of the Revolution. It is a place of considerable historic note. On account of its geographical position, it was often the place of rendezvous of the militia preparing for the battle-fields; of various regular corps, American and British, during the last tree years of the war; and especially as the brief resting-place of both armies during Greene’s memorable retreat. Here, too, it will be remembered, General Waddell had his head-quartes for a few days during the “Regulator war.” I made a diligent inquiry during my tarry in Salisbury, for remains of Revolutionary movements and localities, but could hear of none. The Americans when fleeing before Cornwallis, encamped for a night about half a mile from the village, on the road to the Yadkin; the British occupied a position on the northern border of the town, about an eighth of a mile from the court-house. I was informed that two buildings occupied by officers, had remained until two or three years ago when they were demolished. Finding nothing to invite a protracted stay at Salisbury, I resumed the reins, and rode on toward Concord. The roads were very bad, and the sun went down, while a rough way, eight miles in extent, lay between me and Concord.

My comments are in [square brackets]. The more interesting footnotes from Lossing’s book are included here in (parentheses). Enjoy:

I employed the first morning of the new year (1849), in visiting places of interest at Hillsborough, in company with the Reverend Dr. Wilson. [This must have been Alexander Wilson, the schoolmaster of the Caldwell Institute in Hillsborough and later the founder of the Wilson School in Melville, near Swepsonville, NC.] The first object to which my attention was called was a small wooden building, represented in the engraving on the next page, situated opposite the hotel where I was lodged. Cornwallis used it for an office, during his tarryings in Hillsborough, after driving General Greene out of the state. After sketching this, we visited the office of the Clerk of Superior Court, and made the fac similes and extracts from its records, printed on pages 573-4. We next visited the headquarters of Cornwallis, a large frame building situated in the rear of Morris’s Hillsborough House, on King Street. Generals Gates and Greene also occupied it when they were in Hillsborough, and there a large number of the members of the Provincial Congress were generally lodged. The old court-house, where the Regulators performed their lawless acts, is no longer in existence. I was informed by Major Taylor, an octogenarian on whom we called, that it was a brick edifice, and stood almost upon the exact site of the present court-house, which is a spacious brick building, with steeple and clock. The successor of the first was a wooden structure, and being removed to make room for the present building, was converted into a place of meeting for a society of Baptists, who yet worship there. Upon the hill near the Episcopal church, and fronting King Street, is the spot where the Regulators were hung. The residence of Governor Tryon, while in Hillsborough, was on Church Street, a little west of Masonic Hall. These compose the chief objects of historic interest at Hillsborough. The town has other associations connected with the Southern campaigns, but we will not anticipate the revealments of history by considering them now.

At one o’clock I exchanged adieus with the kind Dr. Wilson, crossed the Eno, and , pursuing the route traversed by Tryon on his march to the Allamance, crossed the rapid and now turbid Haw, just below the falls, at sunset [apparently at Swepsonville]. I think I never traveled a worse road than the one stretching between the Eno and the Haw. It passes over a continued series of red clay hills, which are heavily wooded with oaks, gums, black locusts, and chestnuts. Small streams course among these elevations; and in summer this region must be exceedingly picturesque. Now every tree and shrub was leafless, except the holly and the laurel, and nothing green appeared among the wide reaching branches but the beautiful tufts of mistletoe which every where decked the great oaks with their delicate leaves and transparent berries. Two and a half miles beyond the Haw, and eighteen from Hillsborough, I passed the night at Foust’s house of entertainment, and after an early breakfast, rode to the place where Colonel Pyle, a Tory officer, with a considerable body of Loyalists, was deceived and defeated by Lieutenant-colonel Henry Lee and his dragoons, with Colonel Pickens, in the spring of 1781. Dr. Holt, who lives a short distance from that locality, kindly accompanied me to the spot and pointed out the place where the battle occurred; where Colonel Pyle lay concealed in a pond, and where many of the slain were buried. (About a quarter of a mile northwest from this pond, is the spot where the battle occurred. It was then heavily wooded; now it is a cleared field, on the plantation of Colonel Michael Holt. Mr. Holt planted an apple tree upon the spot where fourteen of the slain were buried in one grave. Near by, a persimmon-tree indicates the place of burial of several others. [This footnote is to a part of the text that I omitted, but the note is interesting and relates also to this part of the text, so I included it here.])The place of conflict is about half a mile north of the old Salisbury highway, upon a “plantation road,” two miles east of the Allamance, in Orange county. Let us listen to the voices of history and tradition.

[Here Lossing gives a long and detailed account of Pyle’s Massacre, which I am omitting.]

I left the place of Pyle’s defeat toward noon, and, following a sinuous and seldom traveled road through a forest of wild crab-apple trees and black jacks, crossed the Allamance at the cotton factory of Holt and Carrigan, two miles distant [the village of Alamance]. (This factory, in the midst of a cotton-growing country, and upon a never-failing stream, can not be otherwise than source of great profit to the owners. The machinery is chiefly employed in the manufacture of cotton yarn. Thirteen hundred and fifty spindles were in operation. Twelve loons were employed in the manufacture of coarse cotton goods suitable for the use of the Negroes. [Slaves wore clothes made from a cheap, coarse fabric called osnaburg. The Holt's made mostly osnaburg and a much finer plaid.]) Around this mill quite a village of neat log-houses occupied by the operatives, were collected, and every thing had the appearance of thrift. I went in, and was pleased to see the hands of intelligent white females employed in a useful occupation. Manual labor by white people is a rare sight at the South, where an abundance of slave labor appears to render such occupation unnecessary; and it can seldom be said of one of our fair sisters there, “She layeth her hands to the spindle, and her hands hold the distaff.” This cotton mill, like the few others which I saw in the Carolinas, is a real blessing, present and prospective, for it gives employment and comfort to many poor girls who might otherwise be wretched; and it is a seed of industry planted in a generous soil, which may hereafter germinate and bear abundant fruit of its kind in the midst of cotton plantations, thereby augmenting immensely the true wealth of the nation. [Boy, was he right about that. In 1849, the only other cotton mills in the Haw watershed were at Big Falls (Hopedale) and Saxpahaw. By 1881, there were 12 and by 1900 there were dozens.]

At a distance of two miles and a half beyond the Allamance, on the Salisbury road [more or less NC 62], , I reached the Regulator battle-ground; and, in company with a young man residing in the vicinity, visited the points of particular interest, and a made the sketch printed on page 577. The rock and the ravine from whence James Pugh and his companions (see page 576) did such execution with their rifles, are now hardly visible. The place is a few rods north of the road. The ravine is almost filled by the washing down of earth from the slopes during eighty years; and the rock projects only a few ells above the surface. The whole of the natural scenery is changed, and nothing but tradition can identify the spot. [Almost makes me think that he did not find the right place.]

While viewing the battle-ground, the wind, which had been a gentle and pleasant breeze from the south all the morning, veered to the northeast, and brought omens of a cold storm. I left the borders of the Allamance, and it associations, at one o’clock, and traversing a very hilly country for eighteen miles, arrived, a little after dark, at Greensborough, a thriving, compact village, situated about five miles southeast from the site of old Guilford Court House. It is the capitol of Guilford county, and successor of old Martinsburg, where the court-house was formerly situated. Very few of the villages in the interior of the state appeared to me more like a Northern town than Greensborough. The houses are generally good, and the stores gave evidence of active trade. Within an hour after my arrival, the town was thrown into commotion by the bursting out of flames from a large frame dwelling, a short distance from the court-house. There being no fire-engine in the places, the flames spread rapidly, and at one time menaced the safety of the whole town. A small keg of powder was used, without effect, to demolish a tailor’s shop, standing in the path of the conflagration toward a large tavern. The flames passed on, until confronted by one of those broad chimneys, on the outside of the house, so universally prevalent at the South, when it was subdued, after four buildings were destroyed. I never saw a population more thoroughly frightened; and when I returned to my lodgings, far away from the fire, every bed in the house was packed ready for flight. It was past midnight when the town became quiet, and a consequently late breakfast delayed my departure for the battle-field at Guilford Court House, until nine o’clock the next morning. [It would be interesting to compare this with contemporary press accounts of this fire.]

A cloudy sky, a biting north wind, and the dropping of a few snow-flakes when I left Greensborough, betokened an unpleasant day for my researches. It was ten o’clock when I reached Martinsville, once a pleasant hamlet, now a desolation. There are only a few dilapidated and deserted dwellings left; and nothing remains of the old Guilford Court House but the ruins of a chimney depicted on the plan of the battle, printed on page 608. Only one house was inhabited, and that by the tiller of the soil around it. Descending into a narrow broken valley, from Martinsville, and ascending the opposite slope to still higher ground on the road to Salem, I passed among the fields consecrated by the events of the battle at Guilford, in March, 1781 to the house of Mr. Hotchkiss, a Quaker, who, I was informed could point out every locality of interest in his neighborhood.

Mr. Hotchkiss was absent, and I was obliged to wait more than an hour for his return. The time passed pleasantly in conversation with his daughter, an intelligent young lady, who kindly ordered my horse to be fed, and regaled me with some fine apples, the first fruit of the kind I had seen since leaving the James River. While tarrying there, the snow began to fall thickly, and when, about noon, I rambled over the most interesting portion of the battle-ground, and sketched the scene printed on page 611, the whole country was covered with a white mantle. Here, by this hospitable fireside, let us consider the battle, and those wonderful antecedents events which distinguished General Green’s celebrated Retreat.

[Lossing describes the Race to the Dan and the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in great detail, a wonderful account that I am omitting here.]

I left the Guilford battle-ground and the hospitable cottage of Mr. Hotchkiss, at noon, the snow falling fast. At four miles distant, on the Salisbury road, I reached the venerable New Garden meeting-house, yet standing within the stately oak forest where Lee and Tarleton met. It is a frame building with a brick foundation. It was meeting-day, and the congregation were yet in session. Tying Charley [his horse] to a drooping branch, I entered softly. A larger number than is usually present at “week-day meetings” had congregated, for a young man of the sect from Randolph county, thirty miles distant, and a young woman of Guilford, had signified their intentions to declare themselves publicly on that day, man and wife. [I think it would be straight forward to identify who this couple was.] They had just risen before the elders and people when I glided into a seat near the door, and with a trembling voice the bridegroom had begun the expression of the marriage vow. His weather-bronzed features betokened the man of toil in the fields, and strongly contrasted with the blonde and delicate face, and slender form of her who, with the downcast eyes of modesty, heard his pledge of love and protection, and was summoning all her energy to make her kindred response. I had often observed the simple marriage ceremony of the Quakers, but never before did the beauty of that ritual appear so marked with the sublimity of pure simplicity.

At the close of the meeting, I learned from one of the elders that a Friend’s boarding-school was near, and, led by curiosity, I visited it. [What school is this?] The building is of brick, spacious, and well arranged. It was under the superintendence of Thomas Hunt, a son of Nathan Hunt, an eminent Quaker preacher. An incidental remark concerning my relationship with Quakers, made while conversing with the wife of the superintendent, caused her to inquire whether I had ever heard of here father-in-law. I replied in the affirmative, having heard him preach when I was a boy, and expressed the supposition that he had long ago gone to his rest. “Oh no,” she replied, “he is in the adjoining room,: and leading the way, I was introduced to the patriarch of ninety-one years. He remembered well when the New Garden meetinghouse was built, and resided in the neighborhood when the wounded and dying, from the field of Guilford, were brought there. Although physical infirmities were weighing heavily upon him, his mind appeared clear and elastic. When I was about departing, and pressed his hand with an adieu, he placed the other upon my head and said, “Farewell! God’s peace go with thee!” I felt as if I had received the blessing of a patriarch indeed; and for days afterward, when fording dangerous streams and traversing rough mountain roads, that uttered blessing was in my mind, and seemed like a guardian angel about my path. Gloomy unbelief may deride, and thoughtless levity may laugh in ridicule at such an intimation, but all the philosophy of schools could not give me such exquisite feelings of security in the hands of a kind Providence as that old man’s blessing imparted.

The storm yet continued, and the kind matron of the school gave me a cordial invitation to remain there until it should cease; but, anxious to complete my journey, I rode on to Jamestown, an old village situated upon the high southwestern bank of the Deep River, nine miles from New Garden meeting-house, and thirteen miles above Bell’s Mills, where Cornwallis had his encampment before the Guilford battle. The country through which I had passed from Guilford was very broken, and I did not reach Jamestown until sunset. It is chiefly inhabited by Quakers, the most of them originally from Nantucket and vicinity; and as they do not own slaves, nor employ slave labor, except when a servant is working to purchase his freedom, the land and the dwellings presented an aspect of thrift not visible in most of the agricultural districts in the upper country of the Carolinas.