Ruth Herndon Shields’s Abstracts of the Minutes of the Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions of Orange County 1752-1766 contains lots of great information. Last night I noticed in it a series of items related to the Catawba people. This is particularly notable because, I believe, the Catawba mostly lived further west than Orange County. Together the entries paint an interesting picture.

First, in March of 1757 a Catawba called Captain Snow appeared and claimed that Michael Synnot possessed a stolen horse. There’s no indication of how the dispute was resolved (if at all), but the presence of a Catawba in Hillsborough Court must have been notable. Also, as we shall see, I think Captain is his military rank, not his name.

Later that same session, the Court made arrangements “to reimburse persons entertaining the Indians traveling to or from Virginia.” This made me curious: Why would Orange County reimburse the cost of Native Americans moving through the area? Presumably Native Americans moved across area farms periodically, but why would the County pay for that?

Over the course of the next year, the minutes show that several claims for reimbursement were entered. In June 1757, William Reed claimed 2 pounds for “dyating 56 Catawba Indians” while they were “on their return trip from Virginia since last March Court.” Some similar claims must have been filed, as the Court in September 1757 appointed a committee “to examine the accounts brought in by sundry persons of this county” related to the Catawba.

In March 1758, William Reed was back, claiming he was owed for “one hog delivered to Cap’t Bull and his Company of Cherokee Indians on their journey to Virginia.” I assume that the Clerk of Court erroneously wrote Cherokee instead of Catawba. Again there is a reference to the rank of Captain. And in the same session of Court, John Dennis reported that Thomas Capper still had the horse that had supposedly been “taken away by the Indians some time ago.”

So, I got out Douglass Rights’ seminal book The American Indian in North Carolina andfound that Rights says: "In 1756 Governor Dobbs stated that no attacks had been made on the frontier, owing principally to the frontier guadsmen and 'the Neighborhood of the Catawba Indians, our friends.' A single mention from the colonial records of the same year, which tells of their aid in pursuit of a roving band of Cherokee marauders, of the recovery of goods stolen from settlers, and of the return of the goods to Salisbury for distribution to rightful owners, indicates the Catawba good will and protection which have made the people of the Carolinas ever indebted to them."

Interesting. It sounds like the alliance between the colonists and the Catawba went a bit further in 1757, with the Catawba being organized into military units and deployed to Virginia for some purpose.

And apparently they passed through Orange County, consuming some forage along the way. That’s why the Court refers to their military ranks, and that is why the Court was reimbursing farmers who had provided the forage.

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

Sunday, May 10, 2009

Booklets on Revolutionary Battles and the Regulation

I have a little collection of books on battles that happened in this area. I only have a small percentage of the ones listed below, but these are all the ones I know of:

The Battle of Alamance

Alamance Day, Burlington, N.C., August 17, 1922: souvenir program, [1922].

Battle of Alamance Bi-Centennial Commission, Battle of Alamance Bicentennial, 1771-1971, Battle of Alamance Bi-Centennial Commission, 1971.

Cooke, William, Revolutionary History of North Carolina in three Lectures; to which is appended a Prelmininary Sketch of the Battle of the Alamance, Cooke and Putnam, Raleigh and NY:, 1853. 237 pp. Illustrated, plates.

Department of Archives and History, Alamance Battleground: Where the war of the regulation came to an end, Division of Archives and History, [1997?].

Department of Archives and History, Alamance Battleground: State historic site, Department of Archives and History, 1960.

Elder, W Cliff, Commemorative souvenir program, May 9-16, 1971, Alamance County Historical Association, 1971.

Fitch, William Edward, The Battle of Alamance: The first battle of the American

Revolution, Alamance Battle Ground Commission, 1939.

Fitch, William Edward, Some neglected history of North Carolina; being an account of the revolution of the regulators and of the battle of Alamance, the first battle of the American Revolution, Neale Pub. Co., 1905.

Fletcher, Inglis Clark, The Wind in the Forest: The colonial frontier of NC 1768-1771 & Battle of Alamance, May 16,1771, Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1957. A novel. 448 pp.

Jones, E O, The War of the Regulators: It's place in history, unpublished thesis, 1942.

Kars, Marjoleine, Breaking Loose Together: The Regulator rebellion in pre-revolutionary North Carolina, UNC Press, 2002.

Kimball, Franklin M, Critters of Cane Creek: A novel, iUniverse, 2007.

McCorkle, Lutie Andrews, Was Alamance the first battle of the Revolution?, E.M. Uzzell & Co., 1903.

Powell, William S., The War of the Regulation and Battle of Alamance, May 16, 1771, State Department of Archives and History, Raleigh, NC, 1965. Fold out map. 32 pp.

Walsh, Colleen Tritz, Loyal Revolt: The Regulator movement in the North Carolina backcountry, 1995.

White, Howard, The Battle of Alamance, May 16, 1771: Two hours of history, Burlington, N.C.: Burlington Chamber of Commerce, [1956]. 22 pages.

The Battle of Clapp’s Mill

Bandy, James M, Cornwallis in Guilford County, 1781: Clapp's Mill and Wetzell's Mill, Greensboro Female College, 1898.

Dunaway, Stewart E, The Battle at Clapp's Mill, 2008.

Steele, Rollin M, The Lost Battle of the Alamance, also known as the Battle of Clapp's Mill: A turning point in North Carolina's struggle with their British invaders in the very unusual year of 1781, [1994].

The Battle of Guilford Courthouse

A Memorial Volume of the Guilford Battle Ground Company, Reece & Elam, 1893.

Cameron, Rebecca & Alfred Moore, A Sprig of English Oak : Lieutenant Colonel Wilson Webster, of His Majesty's 33d regiment of foot, 1781, North Carolina Society, Daughters of the Revolution, 1913.

Dunaway, Stewart E, Like a Bear with his Stern in a Corner - From the Dan to Guilford Courthouse, 2008.

Hairr, John, Guilford Courthouse: Nathanael Greene's Victory in Defeat, March 15, 1781, Da Capo, 2002.

Konstam, Angus, Guilford Courthouse 1781: Lord Cornwallis's Ruinous Victory, Praeger Publishers, 2002.

Rickard, Tim, The Battle of Guilford Courthouse, March 15, 1781, [Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, 1993].

The Battle of Hart’s Mill

Dunaway, Stewart E, The Battle at Hart's Mill, 2008.

The Battle of Lindley’s Mill

Alamance County Historical Association , Ambush on Cane Creek: The Battle of Lindley's Mill, The Association, 1981.

Dunaway, Stewart E, The Battle at Lindley's Mill, 2008.

Newlin, Algie Innman, The Battle of Lindley's Mill, Alamance Historical Association, 1975.

Pyle’s Massacre

Dunaway, Stewart E, Every Blood of them Tories - Complete Guide to Pyle's Defeat, 2008.

Hayes, John T, Massacre: Tarleton vs Buford May 29, 1780, Lee vs Pyle February 23, 1781, Saddlebag Press, 1997.

Troxler, Carole Watterson, Pyle's Defeat: Deception at the racepath, Alamance County Historical Association, 2003.

Troxler, George Wesley, Pyle's Massacre, February 23, 1781, Alamance County Historical Association, 1973.

The Battle of Weitzel’s Mill

Dunaway, Stewart E, The Battle at Weitzel's Mill, 2008.

Moore, Harry, The Liberty Boys at Wetzell's Mill, or, Cheated by the British, Frank Tousey, 1918.

Fiction.

Bandy, James M, Cornwallis in Guilford County, 1781: Clapp's Mill and Wetzell's Mill, Greensboro Female College, 1898.

David Fanning’s Exploits

Dunaway, Stewart E, The Civil War in the American Revolution, 2008.

The Battle of Alamance

Alamance Day, Burlington, N.C., August 17, 1922: souvenir program, [1922].

Battle of Alamance Bi-Centennial Commission, Battle of Alamance Bicentennial, 1771-1971, Battle of Alamance Bi-Centennial Commission, 1971.

Cooke, William, Revolutionary History of North Carolina in three Lectures; to which is appended a Prelmininary Sketch of the Battle of the Alamance, Cooke and Putnam, Raleigh and NY:, 1853. 237 pp. Illustrated, plates.

Department of Archives and History, Alamance Battleground: Where the war of the regulation came to an end, Division of Archives and History, [1997?].

Department of Archives and History, Alamance Battleground: State historic site, Department of Archives and History, 1960.

Elder, W Cliff, Commemorative souvenir program, May 9-16, 1971, Alamance County Historical Association, 1971.

Fitch, William Edward, The Battle of Alamance: The first battle of the American

Revolution, Alamance Battle Ground Commission, 1939.

Fitch, William Edward, Some neglected history of North Carolina; being an account of the revolution of the regulators and of the battle of Alamance, the first battle of the American Revolution, Neale Pub. Co., 1905.

Fletcher, Inglis Clark, The Wind in the Forest: The colonial frontier of NC 1768-1771 & Battle of Alamance, May 16,1771, Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1957. A novel. 448 pp.

Jones, E O, The War of the Regulators: It's place in history, unpublished thesis, 1942.

Kars, Marjoleine, Breaking Loose Together: The Regulator rebellion in pre-revolutionary North Carolina, UNC Press, 2002.

Kimball, Franklin M, Critters of Cane Creek: A novel, iUniverse, 2007.

McCorkle, Lutie Andrews, Was Alamance the first battle of the Revolution?, E.M. Uzzell & Co., 1903.

Powell, William S., The War of the Regulation and Battle of Alamance, May 16, 1771, State Department of Archives and History, Raleigh, NC, 1965. Fold out map. 32 pp.

Walsh, Colleen Tritz, Loyal Revolt: The Regulator movement in the North Carolina backcountry, 1995.

White, Howard, The Battle of Alamance, May 16, 1771: Two hours of history, Burlington, N.C.: Burlington Chamber of Commerce, [1956]. 22 pages.

The Battle of Clapp’s Mill

Bandy, James M, Cornwallis in Guilford County, 1781: Clapp's Mill and Wetzell's Mill, Greensboro Female College, 1898.

Dunaway, Stewart E, The Battle at Clapp's Mill, 2008.

Steele, Rollin M, The Lost Battle of the Alamance, also known as the Battle of Clapp's Mill: A turning point in North Carolina's struggle with their British invaders in the very unusual year of 1781, [1994].

The Battle of Guilford Courthouse

A Memorial Volume of the Guilford Battle Ground Company, Reece & Elam, 1893.

Cameron, Rebecca & Alfred Moore, A Sprig of English Oak : Lieutenant Colonel Wilson Webster, of His Majesty's 33d regiment of foot, 1781, North Carolina Society, Daughters of the Revolution, 1913.

Dunaway, Stewart E, Like a Bear with his Stern in a Corner - From the Dan to Guilford Courthouse, 2008.

Hairr, John, Guilford Courthouse: Nathanael Greene's Victory in Defeat, March 15, 1781, Da Capo, 2002.

Konstam, Angus, Guilford Courthouse 1781: Lord Cornwallis's Ruinous Victory, Praeger Publishers, 2002.

Rickard, Tim, The Battle of Guilford Courthouse, March 15, 1781, [Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, 1993].

The Battle of Hart’s Mill

Dunaway, Stewart E, The Battle at Hart's Mill, 2008.

The Battle of Lindley’s Mill

Alamance County Historical Association , Ambush on Cane Creek: The Battle of Lindley's Mill, The Association, 1981.

Dunaway, Stewart E, The Battle at Lindley's Mill, 2008.

Newlin, Algie Innman, The Battle of Lindley's Mill, Alamance Historical Association, 1975.

Pyle’s Massacre

Dunaway, Stewart E, Every Blood of them Tories - Complete Guide to Pyle's Defeat, 2008.

Hayes, John T, Massacre: Tarleton vs Buford May 29, 1780, Lee vs Pyle February 23, 1781, Saddlebag Press, 1997.

Troxler, Carole Watterson, Pyle's Defeat: Deception at the racepath, Alamance County Historical Association, 2003.

Troxler, George Wesley, Pyle's Massacre, February 23, 1781, Alamance County Historical Association, 1973.

The Battle of Weitzel’s Mill

Dunaway, Stewart E, The Battle at Weitzel's Mill, 2008.

Moore, Harry, The Liberty Boys at Wetzell's Mill, or, Cheated by the British, Frank Tousey, 1918.

Fiction.

Bandy, James M, Cornwallis in Guilford County, 1781: Clapp's Mill and Wetzell's Mill, Greensboro Female College, 1898.

David Fanning’s Exploits

Dunaway, Stewart E, The Civil War in the American Revolution, 2008.

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

A wonderful account of the train to UNC

North Carolina Journal of Law (Vol 1, pp 516-518 , 1904):

“Let the man have been tarred with the University stick and he will tell you along with his after-dinner cigar that he has a notion of some day building a house at Chapel Hill – and there remaining to the end of the chapter in the one place where he believes he can obtain a large and perfect peace. There men cling to the town and its surroudnigns with a memory that is both tenacious and jealous of details.

“A friend was describing to one of these - a graduate before the war – the site of the present Alumni Building. Suddenly the old graduate’s eyes flashed fire:

“ ‘What!’ he exclaimed. 'You don’t tell me they’ve cut down the old college linden! I’d rather they’d have gone without that building forever than that they should have touched that tree!

“And so it goes. Living in the hearts of its scattered children, each tree shrub and rose bush, almost each stone of its serried ranks of rough built walls, bears its own faint story; and it is the indefinable suggestion that seems in time to float out from the inanitmate things that have brushed on human hopes that strangely strikes the newcomer at the moment he places foot upon the campus and brings to the returned a tingling of the blood and a half forgotten smell of the air that at once exhilirate and recall to half sad dreams of byegone days.

“As the shock of death precedes Nirvana, so does one’s abrupt alightment at University Station chill the heart before the delight of his journey’s end. Here you are ona train that comes dashing with a 20th century roar around a curve at forty miles an hour. The coach is full of people – quick, nervous looking people, all with the traveling face, talking, reading papers and magazines, blinking at the dust and cinders that swirl in the windows and doors in the wake of the engine’s panting stress of speed. A cord is pulled, the great train quivers and stopes. You grab your bag and somehow instinctively hurry to the door with a vague idea that you are impeding commerce do you delay. You alight, a bell rings and you see the rear coach disappearing ina cloud of dust around another curve and you find yourself facing two dingy country stores, a more dingy station and half a dozen loose jointed men who, with their hands in their pockets, stand gleaning their last excitement of the day in a vague regard of the curve in the track around which your train has vanished from sight. The transition from the histle of modern travel to the apathy of a country place so small as to defy the ordinary expressions of limitation is numbing; village or handlet would exaggerate University – it is a spot and nothing more, except that the fates of railroad engineering have made it the gate at the end of the present day to the world of Chapel Hill.

“But now there is the clanking of a bell that echoes strangely against the dead, dull air of “University” and the “Chapel Hill Limited” – three freight cars, an engine and one coach that contains in itself the three compartments of first class, “Jim Crow” and baggage “cars” – bucks lazily down from the water tank up the road. Six or seven people climb aboard, a trunk is hoisted into the “baggage car,” and the “captain” waves his hand, the citizens of the Station turn and stare moodily and the Limited sets out for its ten mile run to its destination. I use the word “Limited: advisedly, but the limit is not in time but on speed; it is against the rule to go the ten miles in less than forty minutes. On a fair evening or a fresh morning, the run is a delightful one, if time be not – as it generally is not – of the essence. The track winds along among the hills like a serpent – hills that are full of timber and tangled brush and vivid with color – through close sweeping woods that are redolent of sweet odors, past tall stemmed flowers that invade the windows as we pass, over bridges which span shallow streams that bubble over scattered boulders, flushing rabbits and quail and squirrels that flee perfunctorily from the easy going train and stop to look back with the habit of curiosity with which one regards the passing even of an old friend, past fields and widely separated huts of log and mud surrounded by groves that would grace a mansion, and, so, slowly, onward, the wheels crying weirdly over the ungreased curves, the occasional wanton shriek of the whistle rattling among the oaks of the hilltop or bellowing down the coiling recesses of the gorge. And gradually, from the ‘jumping off place’ of University, there comes an ever deepening spell of the unreal that merges at length into the sane but peculiar world of Chapel Hill.

“This connecting link, with its engine and its solitary coach, is a story in itself, that has ere this done service of its two columns of facetiousness in many a large paper of the North. But far be it from me to treat anything that leads to Chapel Hill facetiously – much less the University train. I felt somewhat like the gentleman of the linden when it fot a coal burning engine, and when a man like ‘Capt.’ Smith stops by the roadside as he did yesterday to deliver a bundle and get in a jub of sweet cider from the apple orchard on the hill, it is nobody’s business but his own. ‘Capt.’ Smith and ‘Capt.’ Sparrow have been with the road since it started and it wouldn’t be the road it is without them. There was once upon a time a Capt. Guthrie, also, but he had the heart of an adventurer and went out into the world – to Hillsboro. It is a ‘great’ road and it leads to a ‘great’ place.”

- R. L. Gray in the News and Observer

“Let the man have been tarred with the University stick and he will tell you along with his after-dinner cigar that he has a notion of some day building a house at Chapel Hill – and there remaining to the end of the chapter in the one place where he believes he can obtain a large and perfect peace. There men cling to the town and its surroudnigns with a memory that is both tenacious and jealous of details.

“A friend was describing to one of these - a graduate before the war – the site of the present Alumni Building. Suddenly the old graduate’s eyes flashed fire:

“ ‘What!’ he exclaimed. 'You don’t tell me they’ve cut down the old college linden! I’d rather they’d have gone without that building forever than that they should have touched that tree!

“And so it goes. Living in the hearts of its scattered children, each tree shrub and rose bush, almost each stone of its serried ranks of rough built walls, bears its own faint story; and it is the indefinable suggestion that seems in time to float out from the inanitmate things that have brushed on human hopes that strangely strikes the newcomer at the moment he places foot upon the campus and brings to the returned a tingling of the blood and a half forgotten smell of the air that at once exhilirate and recall to half sad dreams of byegone days.

“As the shock of death precedes Nirvana, so does one’s abrupt alightment at University Station chill the heart before the delight of his journey’s end. Here you are ona train that comes dashing with a 20th century roar around a curve at forty miles an hour. The coach is full of people – quick, nervous looking people, all with the traveling face, talking, reading papers and magazines, blinking at the dust and cinders that swirl in the windows and doors in the wake of the engine’s panting stress of speed. A cord is pulled, the great train quivers and stopes. You grab your bag and somehow instinctively hurry to the door with a vague idea that you are impeding commerce do you delay. You alight, a bell rings and you see the rear coach disappearing ina cloud of dust around another curve and you find yourself facing two dingy country stores, a more dingy station and half a dozen loose jointed men who, with their hands in their pockets, stand gleaning their last excitement of the day in a vague regard of the curve in the track around which your train has vanished from sight. The transition from the histle of modern travel to the apathy of a country place so small as to defy the ordinary expressions of limitation is numbing; village or handlet would exaggerate University – it is a spot and nothing more, except that the fates of railroad engineering have made it the gate at the end of the present day to the world of Chapel Hill.

“But now there is the clanking of a bell that echoes strangely against the dead, dull air of “University” and the “Chapel Hill Limited” – three freight cars, an engine and one coach that contains in itself the three compartments of first class, “Jim Crow” and baggage “cars” – bucks lazily down from the water tank up the road. Six or seven people climb aboard, a trunk is hoisted into the “baggage car,” and the “captain” waves his hand, the citizens of the Station turn and stare moodily and the Limited sets out for its ten mile run to its destination. I use the word “Limited: advisedly, but the limit is not in time but on speed; it is against the rule to go the ten miles in less than forty minutes. On a fair evening or a fresh morning, the run is a delightful one, if time be not – as it generally is not – of the essence. The track winds along among the hills like a serpent – hills that are full of timber and tangled brush and vivid with color – through close sweeping woods that are redolent of sweet odors, past tall stemmed flowers that invade the windows as we pass, over bridges which span shallow streams that bubble over scattered boulders, flushing rabbits and quail and squirrels that flee perfunctorily from the easy going train and stop to look back with the habit of curiosity with which one regards the passing even of an old friend, past fields and widely separated huts of log and mud surrounded by groves that would grace a mansion, and, so, slowly, onward, the wheels crying weirdly over the ungreased curves, the occasional wanton shriek of the whistle rattling among the oaks of the hilltop or bellowing down the coiling recesses of the gorge. And gradually, from the ‘jumping off place’ of University, there comes an ever deepening spell of the unreal that merges at length into the sane but peculiar world of Chapel Hill.

“This connecting link, with its engine and its solitary coach, is a story in itself, that has ere this done service of its two columns of facetiousness in many a large paper of the North. But far be it from me to treat anything that leads to Chapel Hill facetiously – much less the University train. I felt somewhat like the gentleman of the linden when it fot a coal burning engine, and when a man like ‘Capt.’ Smith stops by the roadside as he did yesterday to deliver a bundle and get in a jub of sweet cider from the apple orchard on the hill, it is nobody’s business but his own. ‘Capt.’ Smith and ‘Capt.’ Sparrow have been with the road since it started and it wouldn’t be the road it is without them. There was once upon a time a Capt. Guthrie, also, but he had the heart of an adventurer and went out into the world – to Hillsboro. It is a ‘great’ road and it leads to a ‘great’ place.”

- R. L. Gray in the News and Observer

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

The [Piper] Donation

UNC's original property was donated to the University by Chapel Hill area land owners who thought that having a University around here would bring property values up (a point upon which they have been suitably vindicated). One of the original donors was Alexander Piper J-a-m-e-s-P-a-t-t-e-r-s-o-n [Update: Piper, not Patterson], who gave (among other things) a tract of land about a mile west of what became the main campus. [Correction: I do not find any record of Patterson donating land; the Daniel map reads "Donation Patterson." Further Update: I think maybe it says "Donation Piper 20 ac." I think this refers to the deed from Alexander Piper to UNC recorded at ODB 5, pg 614.]

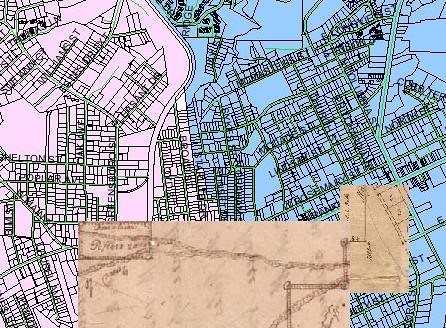

I got to wondering just where the Piper Donation was. I made a bit of a mash up of the 1817 Plan of Chapel Hill, the 1792 Daniel Map of UNC, and the 2009 Orange County GIS tax maps, tying together the dog leg western boundary of the campus, the lots at the corner of Franklin and Columbia Street and the position of the Patterson Donation shown on the Daniel map. The result is very interesting.

The Piper Donation was what would later become Downtown Carrboro:

The tract appears to have run from the rail line on the east to Oak Avenue on the west and from Weaver Street south to the south edge of the lots along Main Street. In other words, some pretty nice real estate by modern standards.

Of course, back in 1792, there was not that much there in terms of development. Two roads ran through the property. The north fork was essentially what is now Weaver Street, turning northward and following Main Street, and then Hillsborough Road to Hillsborough. The south fork led to McCauley's Mill, a grist mill that stood about where University Lake dam is now; no modern road really tracks this course.

You will commonly hear it said that Carrboro grew up where it did because that is where the railhead was - that is, the rail lines didn't used to continue south of Main Street. So a railroad station was built and a grist mill and other industries grew up around the railhead. That area came to be called West End (of Chapel Hill) and was eventually incorporated into the Town of Venable, soon renamed Carrboro after the owner of the big hosiery mill.

But it appears that the railhead was probably located in that spot because it was the edge of the Piper Donation. UNC owned the land, and they must have agreed to have the rail line come to that point. Or so it appears.

I got to wondering just where the Piper Donation was. I made a bit of a mash up of the 1817 Plan of Chapel Hill, the 1792 Daniel Map of UNC, and the 2009 Orange County GIS tax maps, tying together the dog leg western boundary of the campus, the lots at the corner of Franklin and Columbia Street and the position of the Patterson Donation shown on the Daniel map. The result is very interesting.

The Piper Donation was what would later become Downtown Carrboro:

The tract appears to have run from the rail line on the east to Oak Avenue on the west and from Weaver Street south to the south edge of the lots along Main Street. In other words, some pretty nice real estate by modern standards.

Of course, back in 1792, there was not that much there in terms of development. Two roads ran through the property. The north fork was essentially what is now Weaver Street, turning northward and following Main Street, and then Hillsborough Road to Hillsborough. The south fork led to McCauley's Mill, a grist mill that stood about where University Lake dam is now; no modern road really tracks this course.

You will commonly hear it said that Carrboro grew up where it did because that is where the railhead was - that is, the rail lines didn't used to continue south of Main Street. So a railroad station was built and a grist mill and other industries grew up around the railhead. That area came to be called West End (of Chapel Hill) and was eventually incorporated into the Town of Venable, soon renamed Carrboro after the owner of the big hosiery mill.

But it appears that the railhead was probably located in that spot because it was the edge of the Piper Donation. UNC owned the land, and they must have agreed to have the rail line come to that point. Or so it appears.

Saturday, March 28, 2009

Thomas Kirby, Freedom's Lawmaker

In the 1800's three African-Americans served on the Chapel Hill Town Council: Thomas Kirby and Green Brewer during Reconstruction, and Wilson Caldwell in the 1880's. These were what historian Eric Foner has called "Freedom's Lawmakers." I am reminded of the three of them by my post on the Congregationalist school that stood at the corner of Rosemary and Henderson Streets in Chapel Hill (see Freedman's School). I gave there a very brief sketch of one of the school's teachers, Wilson Caldwell. Now let me turn my attention to Thomas Kirby. I'll try to work up something on Green Brewer soon, but he is a more elusive figure.

Reliably, Kemp P. Battle tells us about a lot of 19th century figures in Chapel Hill and Thomas Kirby is no exception. Battle not only mentions Kirby in his History of the University of North Carolina, but also in his Sketch of the Life and Character of Wilson Caldwell. I also read W. J. Peele's A Pen-Picture of Wilson Caldwell, Colored, Late the Janitor of the University of North Carolina. Peele and Battle both give sterotypical views of Kirby (and Caldwell) which must be taken with a lot of salt ('slow shambling gate', 'burly yellow man') , but their comments are interesting nonetheless.

Battle tells us that Tom Kirby was "a big burly yellow man" and an "old issue free man of color" - that is, he was a free man from before the Civil War. Kirby was listed as "Mulatto" in the 1870 census. He worked for the University serving as an assistant janitor with and under Wilson Caldwell. Kirby served in the Old West building. In Battle's words, Kirby "never gained a high character for probity." Or in other words, he was viewed as being somewhat deceitful.

Both Battle and Peele relate parts of a tale about Kirby's purported lack of probity. Battle says: Kirby was "suspected in the days before the war of selling whiskey on the sly to students, a most lucrative business if detection did not follow, as the profits were from one hundred to a thousand per cent on the cost." Peele more graphically relates: "Pious-looking old Tom Kirby, the assistant janitor, was accused of bringing liquor to the students in his boot-legs - and they were indeed capacious enough to accommodate two or three pint ticklers each without impairing the gravity of his slow, shamblig gait." But Battle reassures us "Good behavior wiped out this suspicion, at least to the extent of making him eligible for employment by the University."

Battle also gives this curious account: "I witnessed, in truth I acted as judge, a ludicrous criminal trial of Kirby by a moot court, a trial conducted with all due colemnity, and as able as could be expected of neophytes in the law. Kirby was charged with mixing waters, that is of pouring fresh water from the well into buckets whos contents remained over from the night before. The fact was proved and then Frank Hines, a bright young man, soon afterwards drowned at Nag's Head, was brough in as a scientific expert, to prove that water kept for hours in a bedroom took in solution quantities of carbonic acid gas (carbon dioxide) and other deadly poistons. Of course Kirby was convicted by the jury but no punishment followed."

I found in the 1870 census, that Kirby's wife was Julia, born about 1825 in North Carolina; Kirby was ten years her senior, also born in NC. The 1870 census does not show any children, but Battle tells us that they had a son Edmund, "who was employed in the Chemical Laboratory. He was a preacher and some of his sermons are said to have contained most lurid metaphors, blazing with the transformations he had witnessed in the Laboratory." Battle also mentions that Thomas had a niece, Susan Kirby, who married Wilson Caldwell.

Regarding Green Brewer we know less, but he is listed in the 1880 census:

Green Brewer, Chapel Hill, Orange Co., North Carolina, Age: 48, born in North Carolina Wife: Cornelia, Occupation: Shoe Maker.

Reliably, Kemp P. Battle tells us about a lot of 19th century figures in Chapel Hill and Thomas Kirby is no exception. Battle not only mentions Kirby in his History of the University of North Carolina, but also in his Sketch of the Life and Character of Wilson Caldwell. I also read W. J. Peele's A Pen-Picture of Wilson Caldwell, Colored, Late the Janitor of the University of North Carolina. Peele and Battle both give sterotypical views of Kirby (and Caldwell) which must be taken with a lot of salt ('slow shambling gate', 'burly yellow man') , but their comments are interesting nonetheless.

Battle tells us that Tom Kirby was "a big burly yellow man" and an "old issue free man of color" - that is, he was a free man from before the Civil War. Kirby was listed as "Mulatto" in the 1870 census. He worked for the University serving as an assistant janitor with and under Wilson Caldwell. Kirby served in the Old West building. In Battle's words, Kirby "never gained a high character for probity." Or in other words, he was viewed as being somewhat deceitful.

Both Battle and Peele relate parts of a tale about Kirby's purported lack of probity. Battle says: Kirby was "suspected in the days before the war of selling whiskey on the sly to students, a most lucrative business if detection did not follow, as the profits were from one hundred to a thousand per cent on the cost." Peele more graphically relates: "Pious-looking old Tom Kirby, the assistant janitor, was accused of bringing liquor to the students in his boot-legs - and they were indeed capacious enough to accommodate two or three pint ticklers each without impairing the gravity of his slow, shamblig gait." But Battle reassures us "Good behavior wiped out this suspicion, at least to the extent of making him eligible for employment by the University."

Battle also gives this curious account: "I witnessed, in truth I acted as judge, a ludicrous criminal trial of Kirby by a moot court, a trial conducted with all due colemnity, and as able as could be expected of neophytes in the law. Kirby was charged with mixing waters, that is of pouring fresh water from the well into buckets whos contents remained over from the night before. The fact was proved and then Frank Hines, a bright young man, soon afterwards drowned at Nag's Head, was brough in as a scientific expert, to prove that water kept for hours in a bedroom took in solution quantities of carbonic acid gas (carbon dioxide) and other deadly poistons. Of course Kirby was convicted by the jury but no punishment followed."

I found in the 1870 census, that Kirby's wife was Julia, born about 1825 in North Carolina; Kirby was ten years her senior, also born in NC. The 1870 census does not show any children, but Battle tells us that they had a son Edmund, "who was employed in the Chemical Laboratory. He was a preacher and some of his sermons are said to have contained most lurid metaphors, blazing with the transformations he had witnessed in the Laboratory." Battle also mentions that Thomas had a niece, Susan Kirby, who married Wilson Caldwell.

Regarding Green Brewer we know less, but he is listed in the 1880 census:

Green Brewer, Chapel Hill, Orange Co., North Carolina, Age: 48, born in North Carolina Wife: Cornelia, Occupation: Shoe Maker.

The Freedman's School

In follow up to the essay below on the Preparatory School, let me say a little more that I have recently learned about the subsequent school for former slaves that stood a block to the south at the NE corner of Rosemary and Henderson Streets. Battle provides some more information about the matter in his Sketch of the Life of Wilson Caldwell (1895), but first let me explain (in case you don't know) who Wilson Caldwell was.

UNC Pres. Joseph Caldwell had a slave named November Caldwell who was highly regarded by the Chapel Hill community (as highly regarded as slaves could be said to have been). November's son Wilson was born a slave in 1841. Wilson's mother was a slave of David Swain, so he was given the name Wilson Swain at birth, but after emancipation Wilson went by Wilson Swain Cladwell. Wilson was also very highly thought of in Chapel Hill. He was appointed Justice of the Peace by Reconstruction Governor W. W. Holden. Wilson was also elected to the Chapel Hill Board of Commissioners in the 1880's (the third African American to serve on the Chapel Hill board). Wilson's descendants still live in this area and many of them have dedicated their lives to public service, particularly in the area of law enforcement.

So, here's the tie in with the school, Battle relates in his sketch: "This position [waiter at the University] he held until the beginning of 1869, when he resigned in disgust at the cutting down of his wages so low as not to be sufficient for a decent support in the style to which he had been accustomed . . . Caldwell, after throwing up his post in the University, applied for and obtained from Mr. Samuel Hughes, County Superintendent of Public Schools, a license to take charge of a free school for colored children in Chapel Hill at $17.50 per month . . . In his church relations, he differs from the most of his race at Chapel Hill. He is a memebr of the Congregational Church, which for several years has been supporting a school for the colored in the old Methodist church, bought when the Methodists moved into their larger more beautfiul building on Franklin (or main) street."

So it appears that Wilson Caldwell was the teacher/principal of the school house at the corner of Henderson and Rosemary. And based on the timing, it sounds as though he may have been the first teacher/principal of that school.

Also it seems clear that Wilson Caldwell's school was in the exact same building that had been the Methodist Church. The website of University UMC Church states: "In 1850, Samuel Milton Frost, a university student, served as minister. Determined to carry out Deems’ plan to build a church, Frost traveled the state and raised $5,000 for a church building. The church — dedicated in 1853 — still stands on Rosemary Street."

Battle's History also relates: "he joined the Congregational Church. This denomination did not flourish in Chapel Hill. Soon after Caldwell's death [in 1898] its authorities sold their church building and schoolhouse and left the village."

So here is the approximate chronology of the corner of Henderson and Rosemary Streets:

1853 Methodists build church

1868 Methodists buy new lot on Franklin Street

1869 Congregationalists open school for African Americans

1898 Congregationalists sell school building

UNC Pres. Joseph Caldwell had a slave named November Caldwell who was highly regarded by the Chapel Hill community (as highly regarded as slaves could be said to have been). November's son Wilson was born a slave in 1841. Wilson's mother was a slave of David Swain, so he was given the name Wilson Swain at birth, but after emancipation Wilson went by Wilson Swain Cladwell. Wilson was also very highly thought of in Chapel Hill. He was appointed Justice of the Peace by Reconstruction Governor W. W. Holden. Wilson was also elected to the Chapel Hill Board of Commissioners in the 1880's (the third African American to serve on the Chapel Hill board). Wilson's descendants still live in this area and many of them have dedicated their lives to public service, particularly in the area of law enforcement.

So, here's the tie in with the school, Battle relates in his sketch: "This position [waiter at the University] he held until the beginning of 1869, when he resigned in disgust at the cutting down of his wages so low as not to be sufficient for a decent support in the style to which he had been accustomed . . . Caldwell, after throwing up his post in the University, applied for and obtained from Mr. Samuel Hughes, County Superintendent of Public Schools, a license to take charge of a free school for colored children in Chapel Hill at $17.50 per month . . . In his church relations, he differs from the most of his race at Chapel Hill. He is a memebr of the Congregational Church, which for several years has been supporting a school for the colored in the old Methodist church, bought when the Methodists moved into their larger more beautfiul building on Franklin (or main) street."

So it appears that Wilson Caldwell was the teacher/principal of the school house at the corner of Henderson and Rosemary. And based on the timing, it sounds as though he may have been the first teacher/principal of that school.

Also it seems clear that Wilson Caldwell's school was in the exact same building that had been the Methodist Church. The website of University UMC Church states: "In 1850, Samuel Milton Frost, a university student, served as minister. Determined to carry out Deems’ plan to build a church, Frost traveled the state and raised $5,000 for a church building. The church — dedicated in 1853 — still stands on Rosemary Street."

Battle's History also relates: "he joined the Congregational Church. This denomination did not flourish in Chapel Hill. Soon after Caldwell's death [in 1898] its authorities sold their church building and schoolhouse and left the village."

So here is the approximate chronology of the corner of Henderson and Rosemary Streets:

1853 Methodists build church

1868 Methodists buy new lot on Franklin Street

1869 Congregationalists open school for African Americans

1898 Congregationalists sell school building

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

The Perparatory School

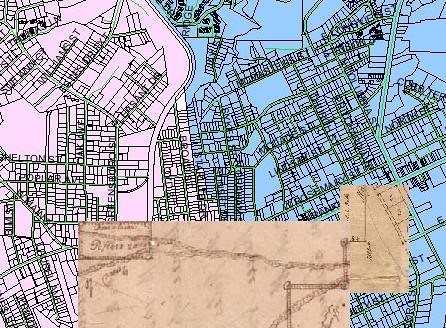

Recently I took note of an interesting detail on the 1817 Plan of Chapel Hill. At the north end of town the map shows the Preparatory School:

As you can see by comparing the modern tax map (on which I have drawn the original lots in red), the Preparatory School was originally at the site that is now the NE corner of Henderson and Rosemary Streets.

Battle's History relates a lot of detail about the Grammar or Preparatory School. A few highlights follow: "In December, 1795 . . . the Board determined to erect a house for a Grammar School . . . a place peculiarly lonely, but near two never-failing springs of purest water."

Presumably Battle means the two springs shown on the 1817 Plan of Chapel Hill. These are not very discernible today, but must be in the vicinity of the old Post Office and somewhat east of there. These springs are the headwaters of Foxhall Branch, a tributary of Bolin Creek.

Battle continues "When Abner W. Clopton gave up the Grammar School in 1819, the University abandoned it . . left to the bats and owls" and under financial pressure in 1831, the University sold "the Preparatory School Acre . . . after some years in the occupancy of a . . . professional hunter . . . Peyton Clements."

A nearby lot has long been said to have been the site of a Freedmen's School, that is, a school for the education of freed slaves after the Civil War. Joe Herzenberg (who lived a block away) often told me so.

Battle mentions later: "Another portion of Grand Avenue was bought by the Methodists as a site for their church, and, when they concluded to build another, some northern Congregationalists bought it for a school and church for the colored. It has since been sold into private hands." By Grand Avenue, Battle means the broad avenue that was once planned to run between lots 11 & 13 and between lots 12 & 14, so it appears that Battle is describing the corner of Rosemary and Henderson Streets.

As you can see by comparing the modern tax map (on which I have drawn the original lots in red), the Preparatory School was originally at the site that is now the NE corner of Henderson and Rosemary Streets.

Battle's History relates a lot of detail about the Grammar or Preparatory School. A few highlights follow: "In December, 1795 . . . the Board determined to erect a house for a Grammar School . . . a place peculiarly lonely, but near two never-failing springs of purest water."

Presumably Battle means the two springs shown on the 1817 Plan of Chapel Hill. These are not very discernible today, but must be in the vicinity of the old Post Office and somewhat east of there. These springs are the headwaters of Foxhall Branch, a tributary of Bolin Creek.

Battle continues "When Abner W. Clopton gave up the Grammar School in 1819, the University abandoned it . . left to the bats and owls" and under financial pressure in 1831, the University sold "the Preparatory School Acre . . . after some years in the occupancy of a . . . professional hunter . . . Peyton Clements."

A nearby lot has long been said to have been the site of a Freedmen's School, that is, a school for the education of freed slaves after the Civil War. Joe Herzenberg (who lived a block away) often told me so.

Battle mentions later: "Another portion of Grand Avenue was bought by the Methodists as a site for their church, and, when they concluded to build another, some northern Congregationalists bought it for a school and church for the colored. It has since been sold into private hands." By Grand Avenue, Battle means the broad avenue that was once planned to run between lots 11 & 13 and between lots 12 & 14, so it appears that Battle is describing the corner of Rosemary and Henderson Streets.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)